Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

“I feel honored to have been a part of this legacy and tradition,” Jackson says of his years at the helm of the Monterey Jazz Festival. “I’m proud of the work that I did.”

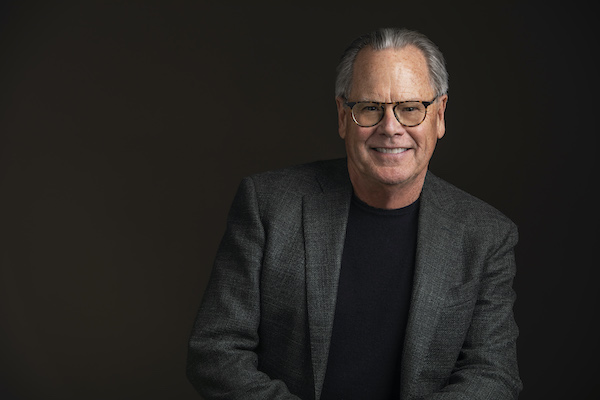

(Photo: RR Jones)“It’s an honor,” said Monterey Jazz Festival artistic director Tim Jackson, when he heard he would be receiving DownBeat’s Lifetime Achievement Award for Jazz Presentation at the 2023 edition of the long-running festival. “DownBeat’s always been my favorite. It’s like Monterey. It’s a legacy brand.”

Jackson, who is stepping down after this year, has played a crucial role in creating and sustaining that legacy in Monterey.

“Tim Jackson took Monterey from being a revered festival that was sort of languishing to the very top of what jazz festivals can be,” observes Jason Olaine, Jackson’s counterpart at New York’s Jazz at Lincoln Center.

“He’s one of the good guys,” says Christian McBride, who this year hosted a pre-festival gala in Jackson’s honor. “Everybody loves him. He communicates very well, he’s not hustling you, he says what he means and means what he says. For everything that Newport has meant for the East Coast, I really think Monterey has meant the exact same thing on the West Coast.”

Even those notoriously crusty bargainers in the background — booking agents — reserve kudos for Jackson.

“You’re talking about a guy who is nothing but a class act,” says Jack Randall, of Boston’s Ted Kurland Agency.

Over the years, Randall has supplied Monterey with such artists as Pat Metheny, Sonny Rollins and Chick Corea and also books the traveling show Monterey Jazz Festival On Tour.

“There’s some big shoes to fill there,” says Randall.

Indeed. Raised in San Jose, California, Jackson studied flute at San Jose State University and started out as an apprentice for Pete Douglas, owner of the unique venue south of San Francisco called the Bach Dancing and Dynamite Society, in Half Moon Bay.

In 1975, after a year off surfing around the world, Jackson and a cooperative of volunteers created the Kuumbwa Jazz Center, in Santa Cruz.

Jackson still runs that cheeky little startup, which today is a $2 million enterprise that presents jazz year-round in its own building. Remarkably, he added Monterey to his responsibilities in 1991, co-producing the festival that year with founding producer Jimmy Lyons, then taking the reins on his own, in 1992.

“My kids were born right about the time I came to Monterey,” recalls Jackson. “When I look back on it, sometimes I don’t know where I had the energy to do it all.”

Having once played the festival himself, one of the first things Jackson did was upgrade what he felt were its shockingly low production values. He replaced all the sound systems, and later added other improvements, such as giant video screens to the sides of the arena stage.

He also doubled the number of stages from three to six and reinstated traditions from Monterey’s early days, such as commissioning new works and appointing an artist-in-residence.

He created Monterey Jazz Festival on Tour; an archive project with Stanford University; the (albeit short-lived) Monterey Jazz Festival Records; and expanded the organization’s educational programs. He also showcased new, young artists such as pianist Gerald Clayton, trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire and flutist Elena Pinderhughes, who had come up in the high school-level Monterey Jazz Festival Next Generation Band.

Jackson generally deflects praise, but happily recalls some of his proudest moments.

“I remember 1994 was an important year for me because it was the first year we re-inaugurated the commission projects,” he says. “We did that big orchestra piece with Billy Childs. And we also brought Sonny Rollins after he hadn’t been here for, I don’t know, maybe since 1972, and we had Max Roach and his M’Boom band. That combination of Max and Sonny and Billy’s premiere piece, that was a highlight for me.”

He also fondly remembers the “fantastic” 2000 Wayne Shorter commission Vendiendo Alegria, 2012’s Miles Ahead project (with the Vince Mendoza Orchestra and Terence Blanchard) and the 2016 tribute to Quincy Jones, a complex undertaking that involved recreating the big band Jones used for three late-’60s/early-’70s jazz fusion albums on A&M.

Creative projects like that have played a big role in Jackson’s job satisfaction.

“That’s one of the things that makes Monterey special,” he says, “that we do take the time to actually curate programs.”

Of course, there have been disasters, too, like the time in 1992 when Arturo Sandoval accidentally boarded a plane from Houston to Monterrey, Mexico, stranding his band in Monterey, California. Or the nights when Monterey’s loyal — yet sometimes curmudgeonly — audience deserted the arena when The Roots (2014) and Tank and the Bangas (2019) took the stage.

But Jackson has always been committed to drawing a younger, more diverse audience, so he took these defections philosophically.

“If, at the end of the weekend, somebody says, ‘I liked everything I heard,’ I’m probably doing something wrong,” he avers. “And the beauty of Monterey is if you truly don’t like something, you can just move to another venue.”

Jackson took a lot of flak in 2015 for the justified criticism that women were not well represented at the festival. To his credit, he responded vigorously.

“Tim has really done a good job since the awareness campaign,” asserts trumpeter Ingrid Jensen, who most recently played Monterey with Artemis.

Monterey had to cancel in 2020, due to the pandemic, but the festival came back at half-speed in 2021 and at full speed in 2022.

Thanks to a surge of interest in live music after the pandemic, as well as generous compensation from the federal government, Jackson is leaving the $4.3 million organization in good shape.

“We’re in a better position financially than we’ve been in 12 years,” says executive director Colleen Bailey, who noted that she especially values Jackson’s balance of creativity and practicality.

“Sometimes artistic directors have a vision,” she says, “but they don’t always understand the business implications. Tim really tries to push the music forward, but he also knows that we have to fill the seats.”

Jackson says he’ll stay on at Kuumbwa for a while, but in the meantime, he plans to spend a lot more time playing flute, traveling and perhaps doing some consulting.

“I look forward to coming to the Monterey Jazz Festival as a civilian,” he says. “I feel honored to have been a part of this legacy and tradition, and I’m proud of the work that I did.”

At the time of this writing, Jackson’s successor had not been chosen. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…