Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

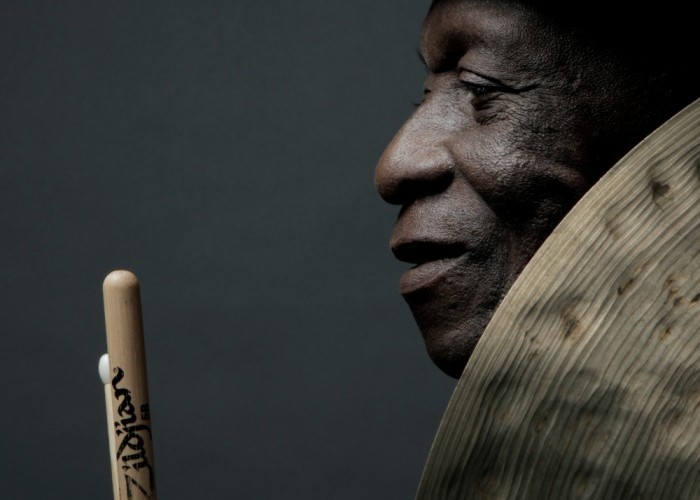

Drummer Tony Allen has claimed to be able to play a different time signature with each limb simultaneously.

(Photo: Bernard Benant)Tony Allen has one of the most recognizable drum sounds on the planet. His polyrhythmic style, which combines swing, African grooves and funk into a swirling blend that virtually demands a physical response, has been hypnotizing listeners and dancers since the late 1960s, when he first came into his own backing legendary Nigerian saxophonist and bandleader Fela Kuti.

Allen and Kuti made about 40 albums together between 1968 and 1979, including three under the drummer’s name: 1975’s Jealousy, 1977’s Progress, and 1979’s No Accomodation For Lagos. Kuti once said, “Without Tony Allen, there would be no Afrobeat,” but disputes over money fractured their professional relationship.

These days, Allen, who’s lived in Paris for decades, doesn’t have much to say about life in Kuti’s Kalakuta Republic compound, a communal household in which the singer, his band and his multiple wives all lived (as did Art Ensemble of Chicago trumpeter Lester Bowie for a period in 1977; he can be heard on the album No Agreement). Allen said his politics are less radical than those of his late boss—“No, no, no … I’m a musician, I’m not a militant”—and prefers to remember the music.

While Kuti arranged all the melodies and horn charts, Allen was in charge of creating the rhythms that underpinned the band’s 12- to 20-minute tracks, which frequently took up entire side of an LP. “It was a live band,” he said, which made sessions quick, disciplined occasions. “The music was played for maybe six months before it was recorded.”

And the long studio tracks had nothing on the live shows. African performance traditions are entirely different from those in North America and Europe.

“When we played in Africa, like with Fela, it was six hours in the night,” Allen said. “It’s only in Europe or America that you can’t do that. But back home, that’s how we play; that’s the culture.”

Allen’s drumming is astonishingly virtuosic; he’s claimed to be able to play a different time signature with each limb simultaneously. But what really makes him stick out is the delicate precision of his touch—his snare sound is somehow feather-light, yet impossible to ignore. But when asked to enlighten a non-drummer about his technique, he demurs.

“I don’t know how to explain this,” he said. “I’ve done some workshops at universities and I show them how it’s done, but you have to see it. I can’t explain it to you with my mouth; it’s not possible. You have to see it in action. Because I never preview what I’m going to play—it comes according to my wavelength. So, it’s impossible for me to explain what I’m playing. You want to know it? I’ll show you how it’s done, and if you can handle it, that’s it.”

In 2017, he signed to Blue Note, and released a four-track EP of tunes associated with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers: “Moanin’,” “A Night In Tunisia,” “Politely” and “The Drum Thunder Suite.” Allen long has expressed an admiration for jazz, but his style couldn’t be more different from Blakey’s—machine-gun press rolls aren’t in his vocabulary. Still, he managed to Allen-ize the material, shifting the groove from the hard-charging swing of the Messengers to a lighter, more dancing style with help from pianist Jean Phi Dary, bassist Mathias Allamane and a four-piece horn section.

He followed that EP with The Source, an 11-track album made with the same band. The music adapted the African funk of his previous work to a soulful, horn-driven hard-bop sound. It still was definitely jazz.

“I wasn’t using fiddle bass before, but I wanted to play [real] jazz, not contemporary jazz—I wanted it to sound like jazz, so I used fiddle bass for the first time,” Allen said. “And the rest [of the band], they’re my musicians from my former records.”

Saxophonist Yann Jankielewicz co-wrote tunes and contributed arrangements, and keyboardist Vincent Taurelle co-produced the record, but it was Allen’s show.

“I’m composing on my drums; I play the bass; I let everybody play what I want them to play,” he said. “I’m not doing a jam band—it’s not a group that everybody can put in whatever they want to play together. No, my band is a band.”

Allen came to the States in late February for a more improvisatory project. He collaborated live with Detroit techno pioneer Jeff Mills at shows in Chicago, Detroit and New York. The duo also is slated to play the Field Day Festival in London during June. Mills has performed with an orchestra and done live soundtracks to silent films, but partnering with Allen—reacting to the ever-shifting beats being thrown at him by a drummer more than 15 years his senior—might be one of his greatest challenges.

“Everybody is used to Jeff Mills on his own, but you’ve never heard him with any other percussion,” Allen said, promising a unique experience. “Everything I’m doing is fusion. That is interesting … I’m a musician, I look at music differently. I just know that any music that interests me, any style that interests me, I feel like collaborating with it.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…