Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

“There’s a certain passion and energy I play with that I never understood until I went to Ukraine,” Friesen says.

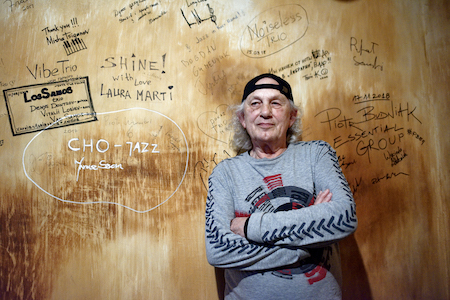

(Photo: Oleg Panov)When David Friesen accompanied reed man Paul Horn on his historic 1983 tour to the Soviet Union, the eclectic Portland bassist was thrilled the trip might take him to what was then the Soviet Socialist Republic of Ukraine. Friesen’s mother was raised in Smila, 18 miles west of Ukraine’s Dnieper River, now a battle-torn front in the Russian war.

“A film crew was going to take us to Smila,” Friesen recalled, “but the week before we left, they backed out.”

Thirty-four years would pass before Friesen finally laid eyes on his mother’s hometown, by which time the Soviet Union had dissolved and Ukraine had become an independent country. But thanks to the bassist’s longtime European personal assistant, Natasha Digtyar, whom he recently married, Friesen played in Smila in May 2017 with Ukraine’s National Academic Symphonic Band, a 40-piece woodwind-and-brass group conducted by Oleksii Vikulov. Friesen not only performed, he was greeted as a visiting celebrity by the local television station, which filmed the concert and escorted him royally through his ancestral home. (A documentary video can be seen here.)

This emotional homecoming launched a deep musical conversation between Friesen and the beleaguered country of his roots that has reinvigorated his career and produced an avalanche of new work. In 2018, he returned to Ukraine and recorded with the Symphonic Band, in the capital, Kyiv. In March 2019, Friesen headlined a jazz festival in the regional capital of Cherkasy with his Circle 3 Trio (with saxophonist Joe Manis and drummer Reuben Bradley) and in October returned to Kyiv, where he recorded a lively quartet set with locals Eugene Dobrovolskyi (vibes) Alex Fantaev (drums) and Mykola Ryshkov (tenor saxophone). In 2020, Circle 3 went back to Kyiv — this time with drummer Charlie Doggett — where they reprised the symphonic music from 2018 for more than 1,000 fans at Philharmonic Hall, then played Kyiv’s 32 Jazz Club as well as gigs in Lviv, Khitomiz and Bila Tserkva. Though the pandemic brought that tour to a screeching halt in March 2020, Friesen was back in Kyiv at the end of 2021, recording eight tracks of yet more new music with Kyiv’s esteemed Mozart String Quartet.

Some of the performances from these tours have already been released on disc. Testimony (Origin, 2020) features live tracks with the Kyiv-based quartet and the Symphonic Band. Interaction (Origin, 2019), a double CD of the Circle 3 Trio, showcases nine tunes from a side trip to the Vienna jazz club Porgy and Bess. Yet to come, also from Origin — “probably this year,” says Friesen — are A Light Shining Through, a 16-part work composed primarily of his 2021 collaboration with the string quartet, and a 12-part work conceived for the Kyiv Symphonic Band, This Light Has No Darkness, with pianist Paul Lees. The piece will have its premiere at the Ravenscroft Concert Hall in Scottsdale, Arizona, in 2024.

“There’s a certain passion the Ukrainian people have,” says the 81-year-old musician of his late-life return to his roots. “It’s a little difficult to explain. But I know there’s a kinship when I play music with them. There’s a certain passion and energy I play with that I never understood until I went to Ukraine.”

Obviously, Russia’s invasion in February 2022 put a hold on Friesen’s Ukrainian love affair — “Everyone I’ve worked with is still alive, so far,” he reports — but it has done nothing to slow the momentum of this indefatigable musician. Known for a work ethic that has spawned more than 80 albums as a leader or co-leader, as well stints with four of the greatest saxophonists in the history of jazz — Dexter Gordon, Joe Henderson, Stan Getz and Sam Rivers — Friesen has plied a wide range of styles that might surprise even those familiar with his work. Like Northwest fellow travelers guitarist Ralph Towner and bassist Glen Moore (of the late, lamented group Oregon), Friesen early on fashioned a virtuosic fusion of jazz, folk, classical and world music. But he’s no stranger to straightahead swing, either. Back in 1980s, he could be found one week at a folk music coffeehouse near Seattle playing intricate duets with guitarist John Stowell and the next week at the Edmonton, Alberta, jazz festival, booming out bass lines for Freddie Hubbard.

“He’s always producing new projects,” says Manis, who teaches at the University of Oregon, in Eugene, and can often be heard with Portland-based pianist George Colligan. “When you’re playing with him, it’s take no prisoners every time.”

Friesen’s first album as a leader was called Color Pool (Muse, 1975), a reference to a life-changing mid-’60s vision that led him to embrace Christianity. Friesen talks about this experience in Episode 2 of a video diary he’s been posting online (at davidfriesen.com) called More Than Jazz. He explains how he saw a pool of beautiful colors being ladled into the world and realized that the colors were “spirit” meant to fill the “containers” of his musical notes.

“If there’s nothing inside the note, then nothing is revealed,” he says. “From that point, I had a purpose in music.”

Friesen’s faith may be what drives the profound sense of joy and celebration that pulses through his music. Orchestral tracks on Testimony, such as “Prelude,” “Still Waters” and, particularly, “Make Believe,” could make even a cynic smile. Without feeling churchy or preachy, his lines flow like litanies of praise for the sheer pleasure of being human and alive.

The new orchestral work, This Light Has No Darkness, is structured even more literally as a sort of pilgrim’s progress. In the spirit of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, it has titles like “Motivation,” “Perseverance,” “Time Changes” and “Tides Turning” that lead the listener through meditation, struggle and, finally, triumph. Indeed, it’s not a stretch to hear Friesen’s bass — now lithe, now angular — as an individual wrestling with, even as it is enchanted by, the sheer grandeur of the world, as embodied by the orchestra.

In his early career, Friesen played a vintage Guinot bass made in France in 1795, but since the 1970s he has used lighter, travel-friendly hybrids, most recently an Hemage bass made for him in 2019 by Austrian designer Hermann Erlacher. The sleek, narrow instrument, which sits more like a cello before him than a bass, weighs less than 12 pounds. As plugged-in basses go, the Hemage produces a quite beautifully round and dark sound, with little of the nasal quality that plagued many electric basses in the ’70s. Friesen often ends phrases with a snapping “pop” that feels unique to the instrument.

“I still like the sound of the old bass,” he confesses. “It has the most depth. But playing the Hemage allows me to transcend the instrument. With the acoustic, you have cracks in the bass and sensitivity to humidity.”

He pauses a beat.

“And you have to carry it,” he adds, erupting in a whimsical laugh that often punctuates his conversations.

A solo virtuoso, Friesen can dazzle a crowd with flying fingers and double- and triple-stops if he wants to, but lately his work has settled into an elegant, melodic simplicity. His compositions flow like the modal music of the ’70s — he uses no key signatures or traditional II–V–I chord progressions — yet they also feel grounded, not floaty or atmospheric.

“I think he works through the harmony like a bass player,” observes the orchestrator of This Light Has No Darkness, Kyle Gordon. “The harmony might be more like modern jazz of the ’70s and ’80s — a lot of it is him exploring colors — but the voice-leading actually works.”

Gordon, who recently arranged saxophonist Grace Kelly’s new album and has also worked in TV and the movies (Bridgerton, Star Wars 9, The Mandalorian), was surprised after completing his orchestrations that Friesen wanted to add another tune. He had a pressing reason for doing so. After he returned to Portland from his 2021 trip to Ukraine, his wife, Kim, after nursing him through a severe case of COVID-19, died from the virus. Five days later, Russia invaded Ukraine. In one tragic week, Friesen had lost his wife of 58 years and access to a place that had become another vital inspiration.

Back in 2009, when Friesen lost his son, Scott, he processed his grief by writing the beautiful tribute “Brilliant Heart.” He turned to the piano again.

“It took two or three weeks,” said Friesen, “but all my feelings about Kim’s death came out.”

“Return To The Father,” a gorgeous, hymn-like tune, now closes This Light Has No Darkness.

The original plan for the new work was to record it with the Symphonic Band in Kyiv. What with the war, and the expense and complication of recording on two continents, Friesen decided to release an electronically generated version first (Gordon used the sample library Note Performer, which sounds remarkably good, especially the individual woodwinds). Friesen still hopes one day to have the work played and recorded in Ukraine.

With his perseverance and irrepressible optimism — and a little luck on the diplomatic front — he’ll probably make that happen. And this time, it won’t take 34 years. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…