Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

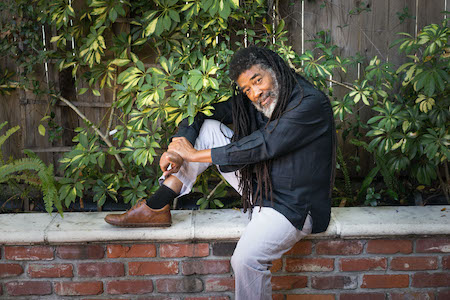

“I work. That’s my joy,” says 80-year-old trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith.

(Photo: Enid Farber)At 80, Wadada Leo Smith seems to be having the time of his life. He maintains a healthy diet, drinking only one cup of coffee a day — along with four to five cups of tea.

He enjoys trying to play video games with his grandchildren. He exercises by walking 10 to 15 minutes around his New Haven, Connecticut, home every evening before bedtime, which is normally on the early side, but later during the NBA basketball season. He now roots for the world champion Golden State Warriors, having switched allegiances several times over the years, choosing to be a fan of excellence rather than suffer through sticking with one team, come rain or shine, out of some misguided tribal loyalty. He is the ultimate fair-weather fan, always moving sunward to that which brings him delight, which is perhaps why he is so joyful.

And, at 80 years of age, what Smith delights in most is to create things, rising daily with the sun to compose music, a ritual he has maintained for decades. “I work. That’s my joy,” Smith says, his long, dark, grey-flecked dreads a stark contrast against his crisp white outfit, elegant but comfortable. As he talks, his mischievous smile and the twinkle in his eyes radiate across the video screen, all the way to Los Angeles, once again enlightening this erstwhile student who studied with him in the City of Angels nearly two decades ago, when the composer and trumpeter was also the director of the African American Improvisational Music Program at the Herb Alpert School of Music at California Institute of the Arts.

Truth be told, Wadada is as he ever was: his humor and enthusiasm in fine form, issuing poetic commentary with a folksy patois that uncovers, beneath his pedigree, the deep roots of his hometown of Leland, Mississippi. The only thing that has truly changed is that his already bright star continues to rise. He is now one of the most celebrated new music composers of this young century.

In this year-long celebration of his eighth decade, Smith has released two more tomes on the TUM label, adding to his extensive legacy: String Quartets Nos. 1–12 and The Emerald Duets. The latter comes as a series of duets between Smith and four notable drummers: Pheeroan akLaff, Andrew Cyrille, Han Bennink and Jack DeJohnette. “Like I told somebody the other day,” Smith says, grinning, “80 is never going to come up again, so you have to do something good with it.”

Some of this music was recently performed live by Smith and others at the 2022 Vision Festival in Brooklyn, New York, where the composer was honored with the festival’s Lifetime Achievement Award. It’s the latest in a series of accolades that include a 2013 nomination for the Pulitzer Prize in Music for Ten Freedom Summers (Cuniform), receiving the 2016 Doris Duke Artist Award and leading the DownBeat International Critics Poll in 2017 as Jazz Artist, Trumpeter and Jazz Album of the Year for America’s National Parks (Cuneiform). Smith was also awarded an honorary doctorate in 2019 from CalArts, alongside actor Don Cheadle, who directed and starred in a film about another famous trumpeter, one Miles Davis.

Smith’s composition class at CalArts was as inspiring as it was challenging. He threw the gauntlet down right away, asking students, “What is your goal? To play the perfect solo?” When I remind him of that, he adds some perspective, saying, “When I was growing up, I heard this language all the time, about going to the woodshed and playing the greatest solo ever. I always thought that was kind of strange, because how are you going to come up with the greatest solo ever until you do it?”

Paul Desmond had said something like that when they met, shortly after the success of the alto saxophonist’s seminal hit with Dave Brubeck, “Take Five.” Even back then, that thinking bothered Smith: “I believe that it’s inspiration that gives you [a great solo], and inspiration will only come to you at the right moment when you’re doing it — not dreaming about it, planning it, trying to construct it. Why spend your life doing that? Just make art.”

But when is “the right moment”? Smith believes every authentic performance has what he terms a “musical moment,” a point of inspiration that is not only unique to the performer, but that “doesn’t exist in anybody else’s music, ever before or in the so-called future.” He said we can find those moments in recorded works through intent listening, but it requires some discipline and restraint to capture them mid-performance. “That’s why I have silence in [my] music, because those reflective moments need that space in order to read the whole inspiration fully,” he explains, revealing the intent behind his well-documented use of profound spaciousness within his pieces.

It was in Smith’s composition class where this writer first had a chance to see and attempt to translate his unique compositional graphic scores — something he calls “Ankhrasmation Symbolic Language,” a series of vivid yet abstract illustrations designed to inspire musicians without dictating too much specificity. “There ain’t no beats in there,” he explains. “There ain’t no counting in this. This is all images and colors and shapes that have to be researched for every single piece.”

Other students who learned Smith’s language ultimately led to the formation of the Red Koral Quartet, the string ensemble that Smith used for Ten Freedom Summers and America’s National Parks and the obvious and only choice to record his string quartets. Three of the four Red Koral members were mentored under Smith at CalArts, and the group as whole are, as he says, “the most proficient in the Ankhrasmation language of any other ensemble, past, present, period.”

But Smith’s fascination with strings predates his discovery of Ankhrasmation. He began writing for string quartet in 1963, publishing his first set of pieces in 1965. He studied masters of the genre, citing Beethoven, Bartók, Shostakovich, Cage and Schoenberg as some of his favorite composers, along with Ornette Coleman and John Lewis. The inclusion of Black and brown composers in a field saturated by the work of white European men is paramount to Smith, who noted that string music from Ethiopia, Egypt and China predated better-known Western forms.

“When I picked up the trumpet, after many of my ancestors picked up the trumpet,” Smith explains, “they took the trumpet out of the cultural and political and social context of Europe by being able to play it differently, and to make different music off it. And when I started to experiment with string music, I took the string quartet out of all its sociopolitical cultural foundation, and my experiment is to see how to use that four-unit ensemble to make music that’s relevant to my social, economic and political experience.” Smith’s quartets are something new, he says, because they utilize “the language of create,” Smith’s preferred term for improvisation. “Improvisation is simply dead,” he pronounces. “Every academic in these institutions now all have got something out on improvisation, whether they be writers, painters, whatever the hell they are. It was never meant for music. And you never find [that word] in the language of the New Orleans musicians or the blues people of that day.”

A year after renouncing “improvisation,” Smith himself stopped being an academic, retiring in 2014 from full-time teaching after his 21-year tenure at CalArts. Originally drawn to the school for the innovative apprenticeship teaching model espoused by its founder, Walt Disney, Smith felt the institute had, over time, slipped into a “conservatory model,” anathema to someone trying to move past conventional musical notions. His departure coincided with a resurgence in his career. During that time of transition he recieved word of his Pulitzer nomination. Perhaps less time spent teaching went toward realizing his artistic goals.

“I think more that it was the time that evolved, as opposed to me having more time,” Smith counters, “because I did just as much work then as I do now. People always tell me, ‘Oh, my gosh, teaching is wearing me down, I can’t do my work. I look at them, and I say that’s just absolutely crap. All you got to do is get up [early] or stay up late and do your work.”

Case in point: Smith had written all of Ten Freedom Summers and recorded it while he was still at CalArts, and much of the music he has released since then had already been written then. The first recordings of his string quartets took place sometime after 2007 and finally completed in 2019. His composing has far outpaced the practical ability to realize all his compositions in sonic form. He intends to finish his 17th string quartet sometime next year. “It’s a gift,” he says simply. “Everybody don’t write as much music as I do.”

Smith’s life has been governed by an unwavering artistic vision, something he also imparted to his students. He praised pianist Keith Jarrett for that very thing, saying how his refusal to compromise on his ideals is what led him to his fantastic success. He still considers Jarrett “a person of great musical character and beautiful sincerity.”

The recollection brings to mind a disagreement Smith had with ECM founder Manfred Eicher. “Manfred had wanted me to record with Keith Jarrett,” he recalls, “and I had asked him about recording with [Jack] DeJohnette. And because he didn’t want me to record with DeJohnette, I didn’t record with Jarrett for him. It could have been resolved easily. He could have said, ‘OK, let’s do Jack and then do Keith, or Keith and then Jack.’ But he said no on Jack, and because I wanted to do Jack as well, I said no [on Keith].”

Smith eventually realized his wish to record with DeJohnette, the long-standing drummer in Jarrett’s Standards Trio. The two met in the late ’60s when DeJohnette was in Chicago to play at Soldier Field with Miles Davis. Smith had relocated to Chicago and ended up playing an informal session with DeJohnette and pianist Muhal Richard Abrams, cofounder of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, of which Smith had become an integral member. It would be many years later that Smith would finally collaborate with DeJohnette, first for the inaugural version of his Golden Quartet in 2000, and a dozen years later for Ten Freedom Summers. After another decade, DeJohnette rejoined Smith as one of the four drummers on The Emerald Duets. In a surprise twist, we hear at times both DeJohnette and Smith on piano and Rhodes electric piano, respectively. “I started using the piano about five years ago,” Smith says. “It’s something that I know, but I use it based off my musicality as opposed to my knowledge of how to play the piano. That fortunately allows me to play the piano as sound, which I really love.”

DeJohnette and Smith on two keyboards represent a unique “musical moment” for Smith, who once told this writer that the goal of every performance should be to discover something you had never played before. “In a system that has a majority of redundant material, that system is at fault; it cannot be creative,” he says. “All you need to balance out maximum redundance is one small instance of something that’s creative … the central balance of a physical body can be knocked off balance with just a slight pluck of the thumb,” citing an ancient Tai-Chi proverb.

Smith says the way to avoid creative inauthenticity is to “follow your inspiration.” Authenticity seems to guide each of the four duets on the new album. All four drummers have a long working history with Smith, and it’s fascinating to hear Smith reinvent himself as a response to what his counterparts are putting forth sonically. The best example of this is the piece “The Patriot Act, Unconstitutional And A Force That Destroys Democracy.” Smith performs the same piece with three of the four drummers on the album (his session with Han Bennink had occurred years before the entire project took shape), with startlingly different outcomes each time. Smith recommends listening to all three versions in one sitting to appreciate the variations on the same theme.

It’s a theme that recalls a difficult time in America’s recent history, but current events dare to compete with the severity of emergency for our ideals and freedoms.

For Smith, the sirens have been blaring for ages. In 1973 he published notes (8 pieces) source a new world music: creative music, a treatise on the importance of creative music in the world around us. In it, he writes: “This music will eventually eliminate the political dominance of Euro-America in this world. When this is achieved, I feel that only then will we make meaningful political reforms in the world: culture being the way of our lives; politics, the way our lives are handled.” Nearly 50 years later, have we moved any closer to achieving this? “No, we have not,” Smith answers bluntly. “And that’s unfortunate, because there are serious waves of art in every category, but it’s not being responded to in the same way as it would have been during the ’60s and ’70s. I wish I had a better report than that, but I don’t. What’s shattering to me most is this: I’ve lived all my life hoping that America would become the kinds of dreams that are expressed in the Constitution, and I always felt that it would move closer and closer to that. But that dream no longer exists.”

It’s a rather dark proclamation from an otherwise eternally jovial figure.

Still, Smith persists in creating music that he hopes will help. One of the most important lessons he teaches is that art is a representation of our lives, our communities, our stories as human beings. Once, I disputed the premise, asking if art could simply exist for its own sake, as a pure act of creation.

Smiling at the memory, Smith answers. “It can’t, and I remember the question. It’s [about] placing art and placing the artist inside the community, because we are social beings as well. To not do it, it won’t destroy one’s life. But if one connects the social aspect to them and their art, then it’s going to benefit the society, either now or later.

“And you don’t have to figure out whether it’s now or later — you just simply do it and keep moving.” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…