Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

“You want to speak to someone’s heart, not just befuddle their brain,” Brunious says.

(Photo: Camille Lenain)When you enter Preservation Hall in New Orleans, it’s like stepping back in time. The small no-frills room looks pretty much like it did when Allan and Sandra Jaffe first opened the now-legendary French Quarter venue on St. Peter Street in 1961. Bare unvarnished floors serve as the stage, surrounded by wooden chairs where the audience sits — until, as often happens, they are moved to get up and march around with a band that celebrates the living past of New Orleans jazz.

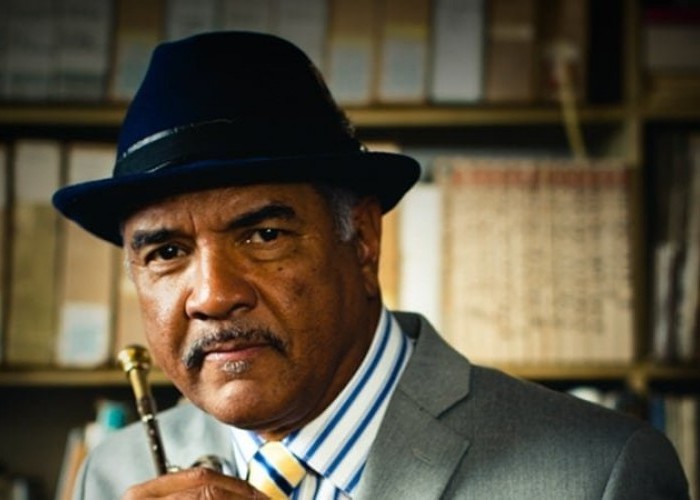

At the center of all the action is master trumpeter Wendell Brunious, the band’s exuberant long-time leader, who’s just been named Preservation Hall’s first-ever musical director. A tall, sharply dressed gentleman, his domain extends far beyond the walls of this tiny “hall.” As Pres Hall’s ambassador to the world, he brings the joyful spirit of New Orleans music to far-flung countries around the world. He’s also a born storyteller who lards his tales with pithy one-liners, as he did for an interview on his home turf.

Spiffy as ever, in a cream-colored suit and elegant brown-and-white spectator shoes, he was accompanied by Caroline Brunious, his Swedish wife of 23 years, who blows a sizzling hot clarinet in the Preservation Hall All-Stars. The scion of legendary trumpeter John “Picky” Brunious — who, like his son, was educated at Juilliard as well as by the brass bands of New Orleans — he’s also the brother of the late John Brunious Jr., who preceded him as Pres Hall’s bandleader.

Our interview ranged from his boyhood memories of Louis Armstrong to close encounters with jazz masters like Dizzy Gillespie, as well as the vitality of the music he passes on to future generations.

Cree McCree: I’ve been to Preservation Hall performances, but I’ve never been back to this room. It feels like a sacred space.

Wendell Brunious: It’s called the Library and it’s got a lot of beautiful old things, like the largest collection of miniature tubas in the world. New Orleans is a living library of music and rhythms, and just being born here is a great advantage. Because you grew up with the music.

McCree: You picked up the trumpet when you were 11, right?

Brunious: That’s when I got serious. But before that I would just take the mouthpiece and make these little duck-call sounds. Sounds kind of like a kazoo. [Grabs a mouthpiece and starts to blow.]

McCree: Wow! [laughs] That’s even better than a kazoo.

Brunious: Then, when I was 10, Louis Armstrong came to town and my dad took us all out to the airport. About a hundred musicians had gone there to meet him, and Louie was one of the last ones off the plane. We thought maybe he missed it [laughs]. Then, suddenly, there he was. The air got thick enough you could cut it with a butter knife, and the whole gang started playing “When The Saints Go Marching In.”

That was magic. God put him here for a specific purpose to teach and influence all of us. If you’re a guitar player, you think you don’t owe something to Louis Armstrong, think again. He revolutionized the whole art of music, especially American music.

McCree: What a thrill that must have been for a kid just starting out on the trumpet. Did your dad give you any specific tips about the trumpet?

Brunious: Not really, because he was always working. He played on Bourbon Street at night, and during the day he worked as a truant officer at Milne’s Boys Home. But on Sunday, when my dad was off, he’d tell everybody go get your horn. There were eight brothers and sisters in our family, and though just me and my older brother John got to the level of playing professionally, everybody played. Dad would say you hit this note, you hit that note, and it’d be this real crazy chord. And he’d say, see, that’s the kind of stuff I like. It was wonderful growing up with that.

McCree: You were still pretty young when you joined Preservation Hall.

Brunious: Yep, 23. I was the youngest person ever to be on the payroll, and it was strange how I came to play here. One night I was playing around the corner on Bourbon Street, blowing my brains off for $88, and my car was parked here. So as I came down the street, I passed right by the gate. I’d never been inside, but it wasn’t but $1 to get in, and when I went inside there was nobody playing trumpet. I said, “You need a trumpet player?” [laughs] And the drummer said, “Man, we don’t let people sit in.” I said, “I’m not sitting in, I come to play, man.” And I took my horn out and played a couple of songs. Allan Jaffe was there, and Kid Thomas [Valentine], and they came up front to see who the heck was playing that trumpet. Kid Thomas had this scowl on his face, and I felt like, “Oh, my God, I had violated something.” But he wasn’t angry, that’s just the way he looked. Then Kid put his hands together and the whole audience started clapping. And I sat down next to him and played the rest of the night.

But I was still playing on Bourbon and barely squeaking out a living. Then one morning my phone rang. It was the great trumpet player Wallace Davenport, who said, “I got a gig for you playing with Lionel Hampton. They need an extra trumpet player tonight.” I must have done OK because after that gig, I went up to New York and joined the Lionel Hampton Band for a while.

McCree: Is that where you met Dizzy Gillespie?

Brunious: No, that was when Dizzy played the New Orleans Jazz Fest. There’s a picture of Dizzy, Mahalia Jackson and Duke Ellington outside Municipal Auditorium. I wasn’t in the picture, but I was sitting there, and Dizzy was holding court. He said, “Man, Charlie Parker told me, keep one foot in the future and keep one foot in the blues.” And I’ve continued to spread that message. Because the blues is not 1, 4 and 5 or 1, 4, 2, 5, 1. You could wake up with a flat tire or a headache this morning, that’s the blues, man. When you hear Charlie Parker playing “Laura,” that’s not a blues. But you hear the blues all through there, that’s what makes your individual voice.

McCree: Circling back to Preservation Hall, I was very surprised to learn you weren’t just the youngest musical director but the first musical director. Why was there never a musical director before?

Brunious: The world has gotten more complicated [laughs]. A lot of our older people have passed on, so I’m gonna help channel the music in the right direction. Kids have so many options today that we gotta bring their focus back to where they need to be to play this kind of music. Back in the 1990s, Ellis Marsalis called me up one day, said, “Would you come teach ’em how to play?” So I made up a class, 40 forms of the blues. Hey, man, you really know how to play the saxophone, but are you delivering the message I want to hear?

McCree: And what is the message you want to hear?

Brunious: You want to speak to someone’s heart, not just befuddle their brain. ’Cause there are enough things that do that, anyway. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…