Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

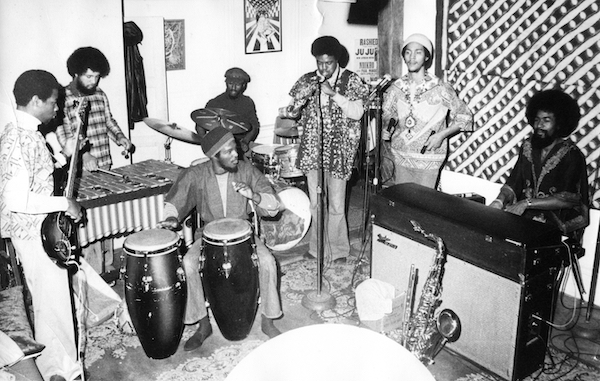

Oneness Of Juju in the studio during the 1970s. A batch of the band’s recordings is being reissued as African Rhythms 1970-1982.

(Photo: Courtesy James "Plunky" Branch)What was the scene like for independent labels back then, especially those run by Black people?

There weren’t a whole lot of them, but there were some. The one thing that made Black Fire so special, both as a label and, even more so, as a distributor, was it was the one place you could get [albums] from these labels. You could get Strata-East, Black Jazz Records, Tribe Records. Black Fire also put out a magazine that was basically a glorified catalog of things you could order through Black Fire.

It was splintered, and not many of the labels had any kind of national distribution at the time. There was a network of little sub-distributors that could service record stores in most of the major urban markets, but it wasn’t 50 record stores. It might have been two or three in Philadelphia or New York or D.C. And, again, having the experience that we had with “The Bottle,” we were able to capitalize on that and supply those stores with these six or eight or 10 labels, plus the other independent people who might put out only one record.

In reading the liner notes for Soul Love Now, it seemed like there were some issues getting Black Fire releases around the U.S., because you didn’t want to play the game and grease the palms of the major distributors.

Yeah, we were trying to not play that game. We were trying to create a new game. We were trying to say that we could create a demand. While that demand might not be tens of thousands of copies, those could create some impact, based on the concentration. And while we might not have wanted to—even if we had the money—we did not have the money to grease those palms.

Our game might be again what we learned from “The Bottle.” If you had a hit record, people would come to you. Without it, you’re just knocking on doors trying to make things happen. African Rhythms had some cache, because we were able to get that record on WHUR, which was a Black college station that functioned like a commercial station. And it was in D.C., which was the sixth largest Black music market in the country. So, we had airplay.

For African Rhythms, we were able to get one of the songs as the theme song to the WHUR daily news show, which was called “The Daily Drum.” So, we had a record that was heard every day. That gave us a leg up we might not have otherwise had.

What was the music scene like in Richmond, Virginia, at that time?

Richmond was a very conservative market. So much so that it was a test market for a lot of Black music, under the theory that if it was successful in Richmond, it could be successful almost anywhere there was Black people. So, people out of Philadelphia or Motown or some of the more commercial labels oftentimes would introduce records there.

Can you talk a bit about working with Gray?

Fantastic. Wild. Very, very political. Jimmy was a unique individual. Very much a revolutionary, in terms of trying to make business and culture mesh. He saw Black Fire as a business, but he also saw it as a political advocacy group. So, working with him was educational. Jimmy was one of those people who would cross all these boundaries until you told him to stop. He might be the engineer on the record, the producer of the record, the DJ spinning the record on radio and the promotion person trying to sell the record. He saw nothing wrong with this, if you didn’t.

Was there a guiding philosophy in how you chose the artists for the label?

It was 50 percent people whose music we liked or could get behind, and 50 percent people who were of the same political mindset. Experience Unlimited ended up being a go-go group with a kind-of-major hit with “Da Butt.” But when we worked with them, they were a Black-rock group doing political things in their neighborhood. So, what attracted Jimmy to Experience Unlimited was the music and their politics. Every group on Black Fire, whether it was Wayne Davis or Baba Dontez or this group called Southern Energy Ensemble or Lon Moshe, if you delve into their biographies, these were cultural, progressive people. Activists. That was the mindset to be on Black Fire.

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…