Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

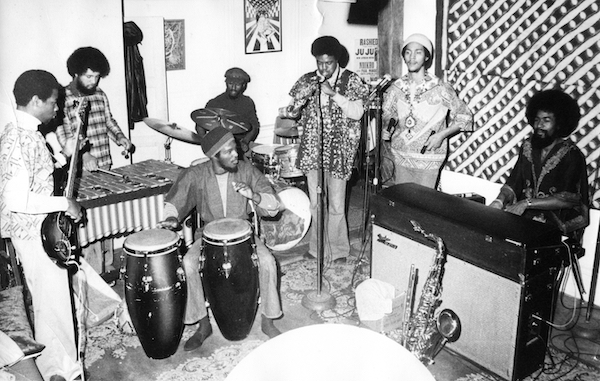

Oneness Of Juju in the studio during the 1970s. A batch of the band’s recordings is being reissued as African Rhythms 1970-1982.

(Photo: Courtesy James "Plunky" Branch)I’m looking at a copy of the magazine while I’m speaking to you, and Jimmy says in it that within Black music, there are cultural seeds of survival. He says, “People are standing still, but we’re looking for the right time to do something now. Now, there’s no excuses. This is your call.”

We just put out the call, and if you heard the call and could be attracted to it, then you fit.

Even with a focus on activism and self-determination, you still had a hit during the ’80s with “Every Way But Loose.”

It seems like in this conversation, I keep going back to “The Bottle,” but that kind of taught us. When we released African Rhythms, one of the first things that Jimmy did was to take the group to Charisma Productions, which was a booking agent based in D.C. They handled Roy Ayers, Hugh Masekela, Norman Connors [and] this group called The Young Senators. It was this idea of having groups that could have some culture and musicianship, but find a larger audience. For Oneness Of Juju, that was maintaining a kind of African orientation, but looking for a way to find a bigger audience.

That song, “Every Way But Loose,” was first released on Black Fire, but I created an offshoot label called N.A.M.E. Brand to release that record, because Jimmy was doing the more political, straightahead jazz things. We didn’t have a falling out, but it was that thing of, how much energy were they going to put into having commercial success versus the politics and culture that we were promoting? So, I went off on my own and made a deal for that record, and it was very big for us. It broke into the Billboard Top 100. In Great Britain, it was a top-10 dance hit. That’s based on the power of Sutra Records, taking it over and promoting it. Remember earlier in the conversation, me saying we didn’t have the money to grease palms? Well, they did.

In the liner notes for the Oneness Of Juju compilation, it mentions that you finally visited Africa in the ’80s. What was that experience like?

Tremendous. I went back six or eight times. And I say it that way because almost anybody can go to Africa once, but it’s the people who go back [that get a fuller sense of it]. You can have this romanticized version of what Africa is going to be like, which can be very disconcerting when you go there and see the physical and fiscal reality of the place. It was very moving for me. I had spent 10, 15 years chasing African culture. Going there and experiencing it was eye-opening and very rewarding.

On one of my trips, I met and played with Fela Kuti. I did a tour of Ghana with several members of my band with the sponsorship of the Ghana Commission on Children and USAID. I also had some ... I don’t want to say negative things, but the name of the group is Juju, and when I went to Nigeria, I ran into some issues with that. I ended up dropping “Juju” from our name, because when I finally went to Africa, I had my album Message From Mozambique, which was released as Juju. They said, “Oh this is great—an African-American group playing juju.” But they put the record on and it was avant-garde jazz, and they were actually angry. “This isn’t juju!” They weren’t thinking that I was trying to pay homage; they thought I was trying to capitalize on it and pervert it in some way. So, when I went to Ghana, I’m going through town and the posters for our tour said, “Plunky And The Oneness Of God.” They won’t even put “Juju” on the posters, because that’s like black magic.

How does it feel to still have your work and the work of Black Fire in circulation and celebrated like this?

Oh, man, it’s one of the most rewarding things of my life. And I don’t think that’s overstating it. Back in those days, we might not have seen it, though. Jimmy often said, “Don’t be surprised if, 20 years from now, people will be coming to talk about this history.” He saw that. I have collected my own papers and photographs and recordings under the belief that it would have some historical significance. So, I can’t say that it was surprising.

I used to say, “Being ahead of your time is just as bad as being behind your time.” But I met Tom Silverman, of Tommy Boy Records, at a music conference, and I said that to him. He said, “Oh, no, it’s better to be ahead of your time. Because then you can be around to say, ‘I told you so.’” DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…