Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

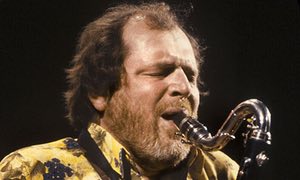

Willem Breuker (1944-2010)

(Photo: Courtesy bvhaast.nl/)The composer, bandleader and reedist Willem Breuker, who died in July 2010 at the age of 65, is often omitted from contemporary assessments of Dutch jazz, where the primacy of pianist Misha Mengelberg (1935–2017) and drummer Han Bennink feels indisputable. Those two musicians left a huge impact on the Amsterdam music scene through the work they created in the Instant Composers Pool Orchestra—work that carries on through Bennink and pianist Guus Janssen, who took over the piano chair for Mengelberg.

But in 1967, they weren’t alone in starting the Instant Composers Pool. Breuker was the third figure involved in launching that highly theatrical, deeply improvisational and fearlessly experimental collective. He was also a key player in the popularization of European free-jazz—he played on Peter Brötzmann’s influential 1968 masterpiece Machine Gun and was an early participant in Alexander von Schlippenbach’s Globe Unity Orchestra. But by the mid-’70s he had moved toward a different practice, situating his love for improvisation and theater in more traditional contexts.

In 1974 he debuted the Willem Breuker Kollektief, which would be his versatile, humor-laden vehicle for a sprawling array of projects and ideas until his death. The medium-sized combo—usually a 10-piece—delivered a lively mixture of Ellingtonian swing, artsy Weimar cabaret, Morricone-inspired scores, circus music, Spike Jones-derived shtick and practiced absurdity in ever-shifting proportions, with loads of improvisation embedded within rigorously arranged, meticulously charted compositions.

The group’s raucous performances were legendary, bringing a theatrical edge that ranged between hammy set pieces to full-blown stage productions. Recently, two of his most devoted sidemen in that band—trombonist Bernard Hunnekink and bassist Arjen Gorter—compiled a mind-melting glimpse into its 38-year history (although Breuker died in 2010, he stipulated that the group could carry on until 2012, which it did, playing its final notes in a concert before the clock struck midnight at Amsterdam’s Bimhuis that year).

Out Of The Box (BVHaast) is a dense 11-CD set drawn from the Kollektief’s rich discography—most of which has been previously available, but the set includes a slew of long out-of-print material as well as several discs of never-before-issued work.

One full disc is devoted to a performance from 1980 in Angoulême, France—it was previously issued as a limited-edition double CD—while an even more sizzling live set taped in Umeå, Sweden, in 1978 has never been previously available. On these discs, there’s no missing the mix of manic energy and sleek precision the group routinely achieved, swinging like mad and playing rich, contrapuntal arrangements. Improvisations often veered deep into free-jazz terrain, and sometimes they went beyond, blurring the line between parodic ineptness and Dadaist silliness. The French concert features an extended vacuum cleaner solo by trumpeter Boy Raaijmakers, and there are stretches of uproarious laughter as the audience responds to some physical humor invisible to the listener.

Another disc highlights Breuker’s love of strings, mixing original pieces and suites adorned with lush arrangements, including some played by the Mondriaan Strings—both as a complement to the Kollektief’s freewheeling performances and as a central facet.

There are romantic, unabashedly sincere readings of classic material by Gershwin (“Rhapsody In Blue”), Kurt Weill and even an adaptation of “Sensemayá,” by the 20th-century Mexican composer Silvestre Revueltas. Another disc features work Breuker’s ensemble created for various Amsterdam theater companies and films.

That interest in film scoring reached its apotheosis in 2003, when the Parisian Cité de la Musique commissioned him to write a new score for a digitally restored version of F.W. Murnau’s classic 1926 silent film Faust. The group premiered the work in Paris and performed it a few times—and a handful of individual pieces were eventually incorporated into the Kollektief’s live sets—but this is the first time the full score has ever been issued, and it largely holds up on its own without the visual component.

The final two discs in the set are called “Happy End” and document the program the band put together as the final farewell to Breuker. It’s a career- and style-spanning program that the Kollektief performed 22 times around the Netherlands in the last months of 2012. Packaged in a container shaped like a cigar box, the discs are accompanied by an 84-page spiral-bound book with detailed annotations of every track by Hunnekink and Gorter and an assortment of essays from music journalists, festival directors and fans—all larded generously with a dazzling array of photographs.

It’s a heady collection, and music this packed with ideas can make for a taxing listening experience, particularly with Breuker’s tendency to front-load his music and leave little breathing room. Still, the set provides a dynamic portrait of his diverse work and it offers a needed corrective to the story of Dutch jazz. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…