Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Two releases serve as reminders of how drummer Buddy Rich and saxophonist Fred Anderson stayed sharp and productive in the latter part of their careers.

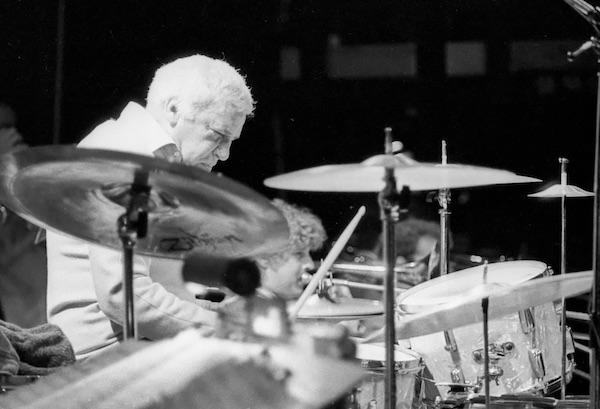

(Photo: Brian O’Connor)In terms of style, background, recognition and—perhaps, most famously—temperament, drummer Buddy Rich and saxophonist Fred Anderson seem poles apart. But digging deeper, they both sought and often achieved the best of jazz: dedication, crafting an individual sound and staying with it for the long haul.

Two releases serve as reminders of how they stayed sharp and productive in the latter part of their careers. That these are also live albums, recorded in sharply different places, showed how much they delivered for their respective audiences.

Rich is introduced as “the world’s greatest drummer” at the beginning of Just In Time: The Final Recording (Gearbox 1556; 71:30 ***1/2), and that accolade isn’t far from the truth. Nor would Rich likely have considered such a statement to be a benediction, as it was a claim he professed throughout his entire life. (Then there are the candid bus tapes posted to YouTube where he made such an assertion rather notorious.) This 1986 date came at a time when his musical life was nearing its end: He died the following year at age 69, but sounded determined to go out fighting.

Performing at Ronnie Scott’s, still London’s most recognized club for traditional jazz, Rich had led big bands for about 20 years by the time that this 16-member ensemble took the stage. This is streamlined swing, heavy on standards and as tightly controlled as Rich’s reputation would indicate. A spirited exchange between the trumpet and saxophone sections shapes “The Trolley Song.” Rich’s focus here is leading from behind, rather than unleashing any extroverted solos. His command of dynamics remained sharp at this late date, especially when he directs the low-end brass moans on the title track and creates a contrast between these runs and Matt Harris’ piano solo. Rich’s daughter, Cathy Rich, also makes a guest appearance with a lively take on “Twisted.” When Rich does let loose on an appropriately dramatic “Porgy And Bess,” he became a relentless force without any unnecessary flourishes.

Anderson never had Rich’s kind of demeanor as a bandleader or while he was running his crucial Chicago bar, The Velvet Lounge. Still, his inner strength required few words. He delved into free-jazz before that idiom gained a foothold in the Midwest and withstood the knocks he received as a trailblazer. But Anderson also created spaces for such sounds to flourish, especially at the Velvet, where he and his contemporaries regularly would jam with a slew of visiting musician who would carve out their own paths. Fred Anderson Quartet—Live Volume V (FPE 26; 57:30 ***1/2) captures one such night in December 1994.

Anderson, 65 years old at the time of the recording, was just about to see a resurgence of disciples, which would continue growing until his passing 16 years later. Possibly, many of the musicians who have become known throughout the jazz world recently had attended a gig like this one, which bartender Clarence Bright recorded on a DAT. Bassist Tatsu Aoki (who also has released live Anderson recordings) held onto it and more recent technology helped clean up the sound. The results present another look at an impactful scene just as it was making another shift.

Aoki and percussionist Hamid Drake had been frequent collaborators with Anderson while trumpeter Toshinori Kondo guested at the Velvet. Also an electronics artist, Kondo paid more than a passing visit to this community: That year he and Drake were performing woth saxophonist Peter Brötzmann’s Die Like A Dog ensemble. (The German musician made Chicago a frequent touring and recording stop back then.)

They all blend in here throughout three extended tracks that essentially are open-ended improvisations within Anderson’s framework. “Analog Breakdown” starts with Kondo’s electronic blasts and builds upward from there. But Anderson’s labyrinthian tone uses quiet force to turn everything around. Drake and Aoki also make the piece swing toward its conclusion. Anderson’s warm low-end notes also add direction to Kondo’s energy on “Probability Distribution.” When the set concludes with “Era Of Rocks,” there’s a sense of playfulness that serves as one more reason why this saxophonist remains so beloved, especially in his hometown. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…