Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

“At this point in my life I’m still looking for the note,” Lloyd says. “But I’m a little nearer.”

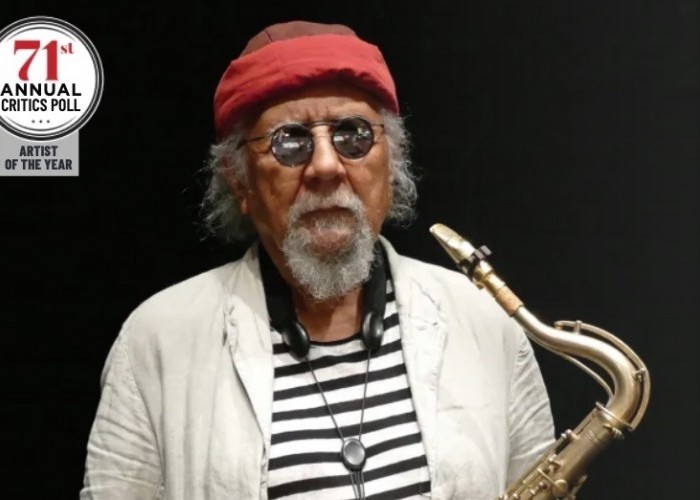

(Photo: Dorothy Darr)If, as Charles Lloyd likes to say, “creativity is going to burst at its seams,” then it’s no surprise that the irrepressibly creative artist breaches the two-dimensional confines of a video-conference screen and emerges as a multidimensional figure.

Lloyd — saxophonist, seeker and self-described late-blooming flower — appears imbued with the serenity of a yogi, the sensitivity of an empath and the constitution of a swimmer just back from a dip in the pool outside his home in the California hills.

That he is 85 and the oldest-ever DownBeat Critics Poll Artist of the Year, as he is this year, is almost beside the point. Lloyd seems to have transcended chronology; to hear a Lloydian musical phrase unfold is to receive the wisdom of several lifetimes in a single breath — suspending, if not upending, one’s perception of reality as a linear proposition.

“There is no ‘time,’” he said, soaking in the negative air ions generated by the ultraviolet rays streaming through the skylight in his bedroom. “There is only ‘now.’”

Early on, Lloyd built enough bridges for several lifetimes — across a racial divide as a young man of color playing with white musicians in his native Memphis; across a genre divide as both a counterculture fixture on Fillmore’s rock stage and DownBeat readers’ 1967 Jazz Artist of the Year; across a commercial threshold, selling a million units of an album, Forest Flower, back in the day.

And, he said, he had no intention of “leaving town” before his work was through. “At this point in my life I’m still looking for the note. But I’m a little nearer.”

Lloyd was just back from a late-May concert in Healdsburg, California, where he played to adoring crowds in a duo with pianist Gerald Clayton. By the time this year’s touring ends, he will have played at least 13 more concerts in venues spanning North America and Europe.

Last year, he played at least 22 concerts worldwide. Most everywhere, he was greeted like a conquering hero by a mix of groups. At New York’s Sony Hall, the overflow crowd ranged from Gen-Z’ers just learning about him to Baby Boomers who regard him like an old friend. The concert presented Lloyd in trio and quintet formats. Playlists and group dynamics diverged. But both groups offered generous quantities of a quality that guitarist Bill Frisell, who played in both, dubbed “the Charles thing.”

“It’s his voice, or his way of coming at something,” Frisell said. “There’s a sensitivity. He’s putting himself out there in danger a little bit, like exposed nerves. There’s a thing where you’re not quite sure where things are going to go that allows for extraordinary things to happen.”

On that June night, micro-events morphed into extraordinary things. During the quintet set, for example, Frisell, unfamiliar with a tune Lloyd called, ventured a contravening series of ideas so logical that they threatened to alter the flow of play until Lloyd, who had laid out, re-entered the fray and, with a small gesture, brought it home. Similarly subtle assertions of authority over the course of the evening built to a kind of crescendo. At show’s end, the audience, hardly calmed by Lloyd’s recitation of excerpts from the Bhagavad Gita, rushed the stage.

The process, in one form or another, repeated itself on stages from Canada to Poland. Yet, for Lloyd, the most personally satisfying moments on the tour might have been offstage at the Memphis stop — a “great homecoming,” he said, courtesy of Manassas High School classmates and a contingent of aspiring saxophonists whose presence recalled memories of youthful days coming up among a rich crop of Memphis musicians: Phineas Newborn, Frank Strozier, Harold Mabern, George Coleman and his dear friend Booker Little. “In Memphis we had freedom and wonder,” he said, glancing at the collection of photos he called his jazz shrine. “That game they were playing out there was not going to taint us.”

Lloyd’s lifelong refusal to play the game is a major reason he has, despite his share of ups and downs, emerged at the top of his field, enjoying the adoration of the masses and a late-in-life recording contract with Blue Note that allows him near-total freedom, according to Don Was, the label’s president. “He was always impervious to musical fashion and true to his musical vision,” Was said, “and it’s kept him vibrant.”

The label followed Lloyd out on a numerological limb last year with its Trio of Trios series of recordings, three sets of threesomes released at approximately three-month intervals. Meanwhile, Was said, that achievement is just prologue to Lloyd’s next release, “the best record of his life.” The album, a studio session recorded in the run-up to Lloyd’s 85th birthday celebration at Santa Barbara’s Lobero Theater in March, will be out next year, and it will feature pianist Jason Moran, bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Brian Blade.

Lloyd is enthusiastic about the release; likewise, his present tour, which will take him from Newport to Berlin, Germany, with an October stop for two dates at Jazz at Lincoln Center. One will feature the long-awaited return of Sangam, the trio with percussionist Zakir Hussain and drummer Eric Harland formed in tribute to Billy Higgins. Lloyd’s association with the drummer, he said, stretched from jams at Ornette Coleman’s Los Angeles home in the 1950s to a duo recording made in January 2001, four months before Higgins “left town.”

That recollection is yet another in Lloyd’s memory bank, a repository in which, despite its seemingly limitless capacity, he ultimately refuses to dwell. For all his memories, Lloyd remains a man of the moment. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…