Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

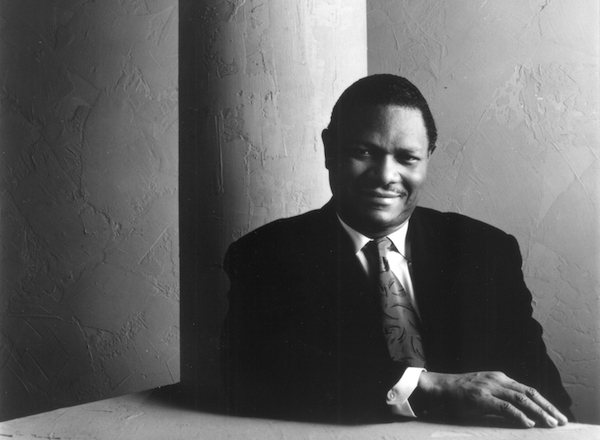

McCoy Tyner (1938–2020)

(Photo: Marc Norberg/Blue Note/DownBeat Archives)A member of the classic John Coltrane quartet of the 1960s, as well as a powerful improviser and potent composer in his own right, iconic pianist McCoy Tyner died March 6 at his home in New Jersey. He was 81.

A 2002 NEA Jazz Master and 2004 DownBeat Hall of Fame inductee, Tyner’s playing style—with its harmonic inventions, predilection for modal fourth voicings and signature emphatic left-hand attack on the low keys—made him one of the most instantly identifiable and influential players in jazz.

“Most people think of McCoy’s music, and obviously I think of that, too, but I mostly think of him as a person, as a man,” said bassist Avery Sharpe, who played with the pianist for 26 years. “He was a considerate cat and a sensitive cat, and amazingly funny. People don’t even realize that. McCoy was like a big brother to me.”

Born Alfred McCoy Tyner on Dec. 11, 1938, he grew up in Philadelphia and began studying piano at age 13 at the Granoff School of Music. Inspired by Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk, Tyner began developing quickly, and at age 15 was thrilled when Powell moved into his neighborhood, taking up residence in the apartment of younger brother and fellow bop pianist Richie Powell.

“I was very fortunate to have a gentleman that inspired me right around the corner in my neighborhood,” Tyner explained to Joe Maita of jerryjazzmusician.com.

By 17, the pianist joined a band led by Philadelphia-based trumpeter Cal Massey that also included alto saxophonist Clarence “C” Sharpe, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Albert “Tootie” Heath.

It was at a matinee performance at the Red Rooster in Philly with Massey’s band where Tyner first encountered Coltrane.

“He was with Miles [in October 1956],” he told this writer in a 2008 interview. “He came home for a sabbatical to spend some time with his mother, Alice, and it was during this period that I met him. But we really got acquainted with each other when he left Miles’ band the first time [in April 1957], and returned to Philly to live with his mother. I used to go by there and play with John. She had an upright piano, and we’d play together at his home. And he’d also come by my place and play with me. My piano was in my mother’s beauty shop ... . So, we used to have jam sessions at her beauty shop with John and guys from the neighborhood. He was 12 years older than me, so he was like a big brother to me.”

Tyner’s first recording session came on Dec. 17, 1959, for the Curtis Fuller Sextet LP Imagination. Around the same time, he joined The Jazztet, led by saxophonist Benny Golson and trumpeter Art Farmer. On May 1, 1960, they recorded the album Meet The Jazztet, which introduced Golson compositions that would become standards: “Killer Joe” and “Blues March.” Tyner’s stint with the ensemble lasted just six months.

By June 1960, the pianist had joined Coltrane’s quartet, setting jazz destiny in motion. Together they created a musical synergy on the bandstand with bassist Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones, and recorded such forward-thinking Coltrane albums as Ballads, Live At Birdland, Crescent and Trane’s masterwork, A Love Supreme.

The 2018 Impulse release Both Directions At Once: The Lost Album documented the classic quartet in stellar form at a March 6, 1963, session at Rudy Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. It was recorded the day before the session that produced John Coltrane And Johnny Hartman.

Tyner explained his perception of the quartet’s work for a story titled “Tyner Talk” in the Oct. 24, 1963, edition of DownBeat: “People sometimes say our music is experimental, but all I can answer is that every time you sit down and play, it should be an experience. There are no barriers in our rhythm section. Everyone plays his personal concept, and nobody tells anyone else what to do. ... We have an overall different approach, and that is responsible for our original style. As compared with a lot of other groups, we feel differently about music. With us, whatever comes out—that’s it, at the moment. We definitely believe in the value of the spontaneous.”

After leaving Coltrane’s quartet in 1965, Tyner generated a string of brilliant Blue Note albums—The Real McCoy, Time For Tyner, Expansions and Extensions—all recorded between 1967 and 1970. Add to that the important Blue Note sessions that Tyner made during the mid-’60s with Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson, Grant Green, Lee Morgan, Hank Mobley, Lou Donaldson and Freddie Hubbard, and you’ve got the résumé of a bona fide jazz legend.

“It’s difficult to comprehend the magnitude of McCoy Tyner’s innovative contributions to music,” Blue Note President Don Was said in a statement to DownBeat. “As a leader and sideman, he recorded dozens of monumental Blue Note albums and has played a major role in shaping the character of our catalog. As an artist, his sense of harmony and rhythm has been pervasive. Mr. Tyner’s signature is forever imprinted upon the musical vocabulary of generations to come.”

Tyner’s albums on Milestone in the 1970s, Blue Note in the 1980s, Impulse in the 1990s and Telarc in the 2000s added to his incredibly rich recording legacy.

His late-period recordings as a leader—Quartet (2007), Guitars (2008) and Solo: Live From San Francisco (2009)—all were released on the Half Note label.

“People always talk about McCoy’s power and the whole thing that he created with Trane, but McCoy had an incredible sense of calm,” Sharpe said. “He could play behind singers, he could play behind anybody, because he was really very sensitive. The way he would comp behind my bass solos was super-sensitive. But at the same time, he could just run everybody off the stage if you want to bring the energy level up ... . I’ve been in all-star situations where cats have egos, but they’ll all look over at McCoy and go, ‘He’s the cat. We’re all great players, but he’s the cat.’”

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…