Aug 26, 2025 1:53 PM

Blindfold Test: Buster Williams

Buster Williams, who at the age of 83 has been on the scene for 65 years, had never done a Blindfold Test. The first…

Among his numerous projects, Noah Preminger has written and recorded music based on the films of a distant relative, director Otto Preminger.

(Photo: Steven Sussman)Concept albums help an artist establish an identity. They’re more than a mere exercise in composing songs as vehicles for blowing or re-envisioning standards.

True concept records come from a different place—the heart, the soul, the deep doubts and the exhilarating discoveries. It’s all about exploring and attacking.

That resides as the wellspring of the music created by Noah Preminger. After topping the category Rising Star–Tenor Saxophone in the 2017 DownBeat Critics Poll, Preminger entered into a prolific phase, raising his profile as a bandleader. This year, he will deliver three albums of intriguingly diverse material: an examination of the works of film director Otto Preminger (a distant relation); a sonic contemplation of the afterlife, accompanied by poetry; and, perhaps the most challenging, an intrepid tenor flight through a dense maze of unpredictable electronic ebullience.

In 2018, Preminger also scored a trifecta, releasing three albums—Whispers And Cries (Red Piano Records), a duo session with pianist Frank Carlberg; his Criss Cross Jazz quartet debut, Genuinity; and Chopin Project (Connections Works Records) by Dead Composer’s Club, a collaboration with drummer Rob Garcia. For the latter, Preminger dug into Chopin’s preludes, phoned Garcia in the middle of the night, and then the two fashioned an ongoing project devoted to the music of composers who have passed. Next up for the Dead Composer’s Club? Right now, it’s a coin toss between the eclectic oeuvre of guitarist/vocalist Frank Zappa and the chants of 11th-century nun Hildegard von Bingen.

Preminger is in perpetual motion nowadays. The 32-year-old, currently living in Boston, sounds a bit worn out from the slog. “I feel like things are missing musically for me,” he said, sipping a dark beer in the West Village watering hole Kettle of Fish in mid-December. “Boston has been great after living in Barcelona for two years. It’s been nice and easy, but I don’t find many people to play with. After four years there, I’m thinking of moving back to New York, even though I struggled in the eight years I lived here before. The day-to-day lifestyle wasn’t doing it for me.”

Preminger suddenly brightens when discussing the first episode of his three-day recording sessions for an album tentatively titled Zigzaw: The Music Of Steve Lampert, which he plans to release later this year. It’s a collaboration with Lampert, a trumpeter and electronic music composer. “It’s my 15th as a leader, and it’s been going awesome,” Preminger said. “Steve, who is a student of [the late composer] Elliott Carter, wrote all this music for me, and it’s serious stuff. It’s the hardest saxophone melody in my life.”

An alumnus of New England Conservatory of Music who earned both undergrad and master’s degrees there, Preminger plays robust tenor with angular flair, emotional intensity and genre-blending authority. He’s shared the stage with Cecil McBee, John McNeil, Billy Hart, Fred Hersch and George Cables, among others, and made his mark as an upstart with a pair of critically acclaimed albums for Palmetto. He continued following his muse while developing his singular voice as saxophonist and composer.

“I have a weird career,” Preminger said. “Critics seem to like what I do. I get great reviews, and I’m often in the list of top records of the year. But my straw is not the one that’s drawn for work. I don’t get the opportunity to play that much. I have limitations—in terms of how other musicians play in wonderful bands on a regular basis and get to travel and perform. For me, it’s OK, though. I’m on a different path.”

Preminger stressed that for a project to be a good fit, all the cards need to be perfectly lined up; otherwise, it’s too strenuous and not enjoyable. “Most importantly, the music has to be satisfying,” he said. “You can only play so loud and so intense and with so much passion. Then it’s cut off.” Not one to mince words, Preminger reflected on John Coltrane’s short career: “I understand why Trane ended when he ended, because writing chord changes and melodies and blowing on them becomes not fun anymore. There’s only a certain point you can get to, a certain point when you can’t scream that loud anymore. Trane really, really lived the music, but couldn’t do it anymore. He couldn’t find where else to go. That’s the end. It doesn’t go on forever.”

Even though Preminger isn’t fully satisfied, career-wise, these days, bring up another special project, and he beams. Case in point: the soulful, sensitive Preminger Plays Preminger, released by the vinyl-only label Newvelle Records and featuring an all-star cast, including his regular bassist Kim Cass and two newcomers to his recording history: pianist Jason Moran and drummer Marcus Gilmore. “I need to be passionate about a project,” Preminger said. “This was another concept, another direction. And overall, it was something to do that was fun.”

The saxophonist’s connection to Otto Preminger has been a subject of personal intrigue for years, ever since Ran Blake approached him during his first term at NEC. “Ran greeted me on the front steps,” he said. “He told me, ‘Noah, I’ve been waiting for you.’ But he was disappointed when I told him that I was unfamiliar with Otto’s films. At that point, I was only 18.”

Blake inspired Preminger to begin exploring Otto’s work. First, he learned that the director was a horrible person who treated women and crew members in misogynist ways. Then he dug deeper to discover that Otto was a distant relative. “My great-grandfather and Otto were supposed to have been first cousins,” he explained. “But most of the people who knew for sure were dead. But my grandmother, who died last week, told me that Jack Preminger and Otto were first cousins and grew up in a town called Czernowitz in the Austria-Hungary empire.”

Several years ago Preminger got the idea to interpret some of Otto’s soundtrack music and then compose his own scores based on his films. He watched more than 15 movies to come up with four pieces based on movie themes and four original compositions. He got the green-light from Newvelle after finding success with his 2016 recording for the label, Some Other Time.

Tracks include the Americana-tinged theme from the 1954 film River of No Return (starring Marilyn Monroe and Robert Mitchum), which opens with a tenor flight and riveting bass solo. “I love the opening credits to the film,” Preminger said. “It was the perfect arrangement for me. It’s like a country folk song with the prairie, cowboys.” Another standout is a quiet piece Preminger wrote for the 1953 classic Stalag 17, a tale of two prisoners of war trying to escape, but are shot down outside the World War II prison camp. (Otto didn’t direct, but had an acting role as the arrogant Colonel von Scherbach.)

For Preminger’s originals, he watched the films and isolated scenes or movements, which he wrote for. He’d hit “mute” and replay scenes until he had written melodic motifs on piano. On the haunting “For Bunny Lake Is Missing” (inspired by the 1965 thriller Bunny Lake Is Missing), Preminger focused on a scene in which a child is ripped away from a swing set. He also composed a sober piece, “For Laura,” based on a scene from the 1944 classic. “I love the song from the film, but I decided to go for something better,” he said.

“What I got from Percy was the dignity of playing the bass,” Buster Williams said of Percy Heath.

Aug 26, 2025 1:53 PM

Buster Williams, who at the age of 83 has been on the scene for 65 years, had never done a Blindfold Test. The first…

Don and Maureen Sickler serve as the keepers of engineer Rudy Van Gelder’s flame at Van Gelder Studio, perhaps the most famous recording studio in jazz history.

Sep 3, 2025 12:02 PM

On the last Sunday of 2024, in the control room of Van Gelder Studio, Don and Maureen Sickler, co-owners since Rudy Van…

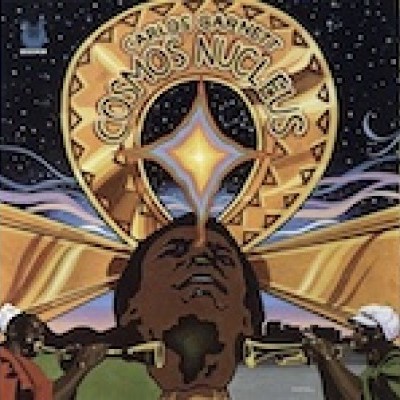

The Free Slave, Cosmos Nucleus and Sunset To Dawn: three classic Muse albums being reissued this fall by Timer Traveler Recordings.

Aug 26, 2025 1:32 PM

Record producer and “Jazz Detective” Zev Feldman has launched his next endeavor, the archival label Time Traveler…

Butcher Brown, clockwise from top left: Marcus Tenney, DJ Harrison, Morgan Burrs, Corey Fonville and Andrew Randazzo. (Keyboardist Harrison couldn’t make the gig, so special guest Jacob Mann sat in with the band at the Reno Jazz Festival.)

Aug 19, 2025 12:41 PM

The band known as Butcher Brown has enjoyed the last half-decade basking in the glow from the twin engines of critical…

This year’s Jazz em Agosto set by the Darius Jones Trio captured the titular alto saxophonist at his most ferocious.

Aug 26, 2025 1:31 PM

The organizers of Lisbon, Portugal’s Jazz em Agosto Festival assume its audience is thoughtful and independent. Over…