Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

In Memoriam: Ken Peplowski, 1959–2026

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

Pianist Pat Thomas recently has enjoyed some serious momentum.

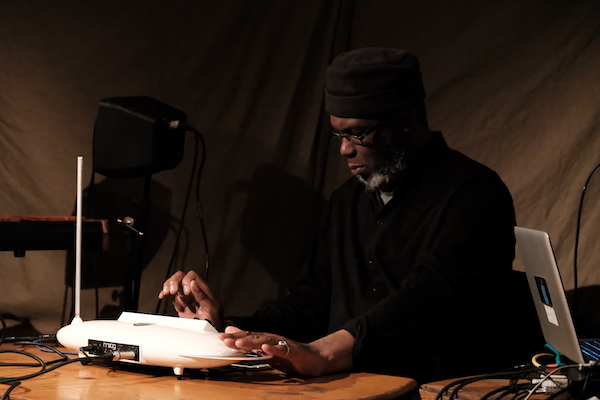

(Photo: Cristina Marx)Keyboardist and improviser Pat Thomas, 59, has been a prolific polymath on the U.K. jazz and improv scene for four decades, working in a dizzying array of projects and styles. Yet, he remains an overlooked figure in much of the world, especially in the States, where he’s never had the chance to perform.

Even in his homeland, Thomas often has been taken for granted, although that began to change in 2014 when he received one of the prestigious Paul Hamlyn Foundation Awards for Artists—an annual U.K. honor akin, albeit more financially modest, to a MacArthur Fellowship.

In 2019, however, Thomas enjoyed some serious momentum, unleashing a barrage of excellent recordings—from the ruminative post-bop piano trio heard on BleySchool, the free improv of the collective trio Shifa, an exploratory trio with reedist John Butcher and drummer Ståle Liavik Solberg on Fictional Souvenirs and a stunning live solo piano set of Duke Ellington music available digitally from London’s Café Oto. The Truth, a duo recording with alto saxophonist Matana Roberts, is due out this spring from Oto’s imprint, Otoruko.

Yet the project that just might galvanize the most interest in his work is Super Majnoon (East Meets West) (Otoruko), the dazzling second album by the quartet Ahmed, which salutes the fascinating marriage of jazz and Arabic music pioneered by the bassist and oud player Ahmed Abdul-Malik. Along with alto saxophonist Seymour Wright, bassist Joel Grip and drummer Antonin Gerbal, Thomas reduces Abdul-Malik’s themes into fiercely rhythmic kernels and then rides them into infinity with a relentless churn of constantly shifting grooves.

The foursome’s first-ever performance was released as New Jazz Imagination (Umlaut) in 2017, capturing an extended, hard-driving interpretation of Abdul-Malik’s “Anxious.” The recordings on the new album were made at Hong Kong’s Empty Gallery and Café Oto in 2018, and represent a quantum leap in terms of focus and intensity.

“The first record is really great, but we were still searching,” said Thomas. “On this one, we felt like we started to create a sound for Ahmed.

“We had to find a context for playing Abdul-Malik’s music, and I think that’s how we found this collective way of playing. If we were just freely improvising, it would be very different music. The compositions are the bedrock, the foundation for what we’re doing. We wanted to do his music, but we also wanted to put our own mark on it, so we came up with this approach. We’re all coming from the improvised thing while respecting the fact that there’s this compositional framework, and we’ve used the rhythmic concepts more.”

On first glance, the music strays from its roots, but there’s an undeniable connection in its trance-like intensity. Thomas and Wright dig deep into terse, cycling phrases over the shape-shifting propulsion of Grip and Gerbal, each steadily chipping away at the theme through fine-tuned rhythmic alterations.

“Even though you might hear the repetition, it’s not like systems music where everyone is doing the same thing,” Thomas explained. “That’s why people don’t get bored with it—we’re using this traditional free improvisation and jazz approach, shifting around the rhythms, so even though the material might be static, it doesn’t get boring because the rhythm section is never doing the same thing.”

This summer the quartet has planned collaborative performances in Europe with Morocco’s Master Musicians of Jajouka, whose current leader, Bechir Attar, inspired part of the album title when he used the Arabic slang “majnoon”—or crazy—to describe the musicians. DB

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…