Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

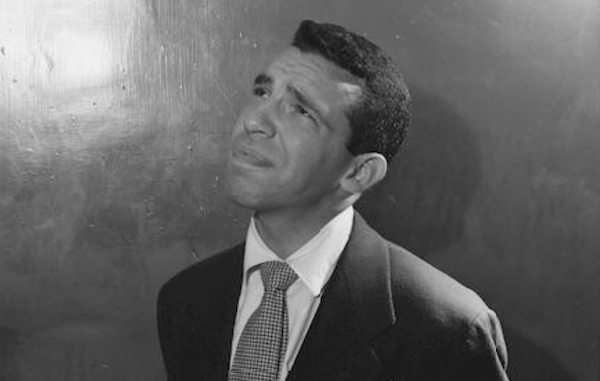

Buddy Rich at New York’s Arcadia Ballroom in May 1947

(Photo: William Gottlieb/Library Of Congress)Buddy Rich died in 1987 at the age of 70. For 68 of those years, he was one of the world’s greatest drummers, first as a child prodigy in vaudeville, then a star sideman, leader and personality. He navigated the swing era, Hollywood, bebop, the TV sitcom and talk show couch, and then finally turned out the last light of his big band.

This is a big story to compress into Buddy Rich: One of a Kind (The Making of the World’s Greatest Drummer) (Hudson Music) by Pelle Berglund, which is an edited version of an original 2018 text from Sivart Books. Gone are many pictures, a timeline and (unfortunately) an index. The text survives—as well as a number of typos and errata, including a reference to “Carnegie Hall’s large stage in Chicago.” It also adds a few new ones of its own. Inaccuracies are rare, though, and almost too trivial to mention.

Though Berglund combs relevant memoirs and press accounts for details, Rich’s formative childhood and early New York days left little documentation, a vacuum he pads with milieu. Rich was a hyperactive toddler when he began banging out miraculously intuitive rhythms. Drummers were a popular attraction in vaudeville, because they were physical. Like tap dancers, they catered to the eye, as well as the ear. Young Rich studied them obsessively. By the time he was 4, he had no memory of ever not playing the drums. His gift became his destiny without ever asking his consent. It chose him. Berglund writes with an orderly clarity about how he managed, but seldom pauses for the enlivening insight, interpretive flourish or incisive probe into the particulars of technique.

Momentum hits its stride with Artie Shaw and Tommy Dorsey, where Rich enjoyed his first taste of the big time—landing spots in MGM musicals and sparking a romance with Lana Turner. He and Frank Sinatra fought as roommates on the road with Dorsey, then found great friendship after leaving the band. But before a stint in the Marines, Rich squeezed in an uncredited spot in Robert Siodmak’s Phantom Lady, which film noir buffs might know for its surreal jam-session sequence where Rich’s off-screen drum solo becomes a kind of maniacal opioid to Elisha Cook Jr.’s on-screen frenzy.

Rich joined the Marines to fight the Germans but instead wound up fighting flagrant anti-Semitism, a battle that landed him in the stockade. After his discharge, he marked time with Dorsey again, before launching his first big band. But the old troupes were sinking fast, and new ones were being dragged down in the undertow. Berglund paints a bleak picture, as Rich fought a two-front war with his sidemen against bebop and drugs.

After the breakup of another band, Rich found a partner in trumpeter Harry James and a place with Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic. It was a volatile relationship; Rich’s recklessness with money was not something Granz cared to subsidize. But the ’50s was crowded with TV, tours, marriage and a daughter, Cathy, who is a major source for Berglund. In 1957, Rich vainly tried to give up the drums for a singing career. Then in 1959, a massive heart attack almost achieved what he could not. Doctors said he would never play again.

Two months later he was back.

Berglund describes Rich’s attempts to balance domestic stability and musical adventure, which in 1966 finally led the drummer back to a big band. This time it clicked. The band would sustain Rich and become the personification of his integrity, letting him enjoy the privileges of fame on his own terms.

For this, Berglund suggests, Rich owed much to talk-show host Johnny Carson. “Carson recognized Buddy’s natural quick wit,” he writes, “and didn’t hesitate to use it humorously. Going forward Rich … became much more than a jazz drummer—he was now an entertainment personality.” Berglund gives a full picture of the band’s 20-year history and Rich’s leadership style in its many dualities, from defender of principle (canceling a South African tour) to complete jerk (the famous bus tapes).

Rooted in the rules of show business, however, Rich never disappointed an audience. Berglund helps explain how. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Hammond came to the blues through the folk boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which he experienced firsthand in New York’s Greenwich Village.

Mar 2, 2026 9:58 PM

John P. Hammond (aka John Hammond Jr.), a blues guitarist and singer who was one of the first white American…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…