Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

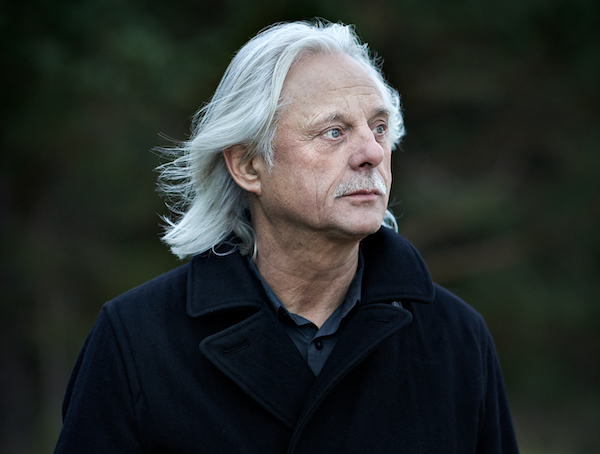

Fifty years ago, Manfred Eicher co-founded Edition of Contemporary Music, better known as ECM, and has issued more than 1,600 titles spanning jazz and classical sounds.

(Photo: Kaupo Kikkas)In one large room, cabinets with massive archives line the walls, and another area belongs to the design station for the label’s legendarily subtle and refined album cover graphics, currently created by Sascha Kleis, in collaboration with Eicher. (Previous designers include Barbara Wojirsch and Dieter Rehm.)

In a rare touch of whimsy, the room also houses a female mannequin sporting an ornate cap once owned by drummer-bandleader Paul Motian (1931–2011), who recorded influential ECM albums in a trio with guitarist Bill Frisell and saxophonist Joe Lovano.

“Paul was a good friend,” Eicher said, “and a great musician whom I’d admired since Bill Evans’ Village Vanguard recordings [1961]. Conception Vessel [1973] marked Paul’s debut as a composer and leader. I’m glad to have encouraged him on that path.”

On the office’s far end, ECM’s founding (and funding) partner Karl Egger’s health food and wine company LaSelva has a showroom combining its products with an ECM record store, with a small performance space attached. The night before DownBeat’s visit, the ECM-aligned duo of cellist Anja Lechner and guitarist Pablo Márquez performed there.

Egger, who ran the Elektro-Egger record store, played a key role in the label’s origin story, offering Eicher a seminal record-making opportunity. The result: pianist Mal Waldron’s Free At Last, recorded on Nov. 24, 1969, at Tonstudio Bauer in Ludwigsburg, West Germany. It became the first ECM release, with early partner Manfred Scheffner (who died in September at the age of 79) listed as producer.

ECM’s 50th anniversary has been celebrated at numerous festivals this year, including the Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, Tennessee, the Healdsburg Jazz Festival in California and the Montreal Jazz Festival.

More celebrations are forthcoming. One will be at the Deutsches Jazzfestival Frankfurt in Germany on Oct. 23–27. SFJAZZ in San Francisco will salute the label Oct. 24–27, with performances by 10 acts; Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York will present an ECM tribute Nov. 1–2; The Skopje Jazz Festival will spotlight ECM Oct. 17–20 in Skopje, Macedonia; and Flagey will present the “ECM 50th Anniversary Weekend” Nov. 21–24 in Brussels, Belgium.

Despite the numerous tributes, Eicher admitted, “I’m not a celebration kind of guy. We will do a few things [to mark the anniversary], but I mostly want to do the work, and just let people [hear the music]. ... That’s the most important thing.”

In a 1975 Saturday Review article, writer Chris Albertson noted that Eicher’s “sensible approach to jazz recording, perceptive ear, venturesome spirit, sensitivity, and stringent technical demands are widely appreciated now, but they will be even more appreciated in years to come.” True enough.

Last January, the celebratory year commenced with a two-night, ECM mini-fest, part of Manhattan’s Winter Jazzfest, at (Le) Poisson Rouge. The roster included pianist Shai Maestro, trumpeter Ralph Alessi, drummer Billy Hart and the piano duo of Iyer and Craig Taborn.

Eicher, who tends to eschew public appearances, traveled to New York for the occasion, which was sandwiched between two other important matters: He visited the rural New Jersey home of longtime friend Jarrett, whose health issues have interrupted his music-making, and he produced a recording session by trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith.

Amid a busy Gotham weekend, Eicher sat down in the lobby of his Midtown hotel, over a pot of tea, and spoke about his adventures.

Regarding his perspective after 50 years, Eicher offered a pithy assessment of the ECM manifesto, as such. “It is all about curiosity,” he said. “It began that way and I am still pursuing that. I am always searching for new sounds.”

Soon after the 1969 Waldron recording, Eicher was drawn deeper into officially starting a label, though without any particular role models: “It was more a simple matter of following my musical interests. This gradually led to what was perceived as the label’s ‘identity.’ But there wasn’t a grand plan. I just wanted to make some recordings and had some ideas about sound in mind.”

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…