Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

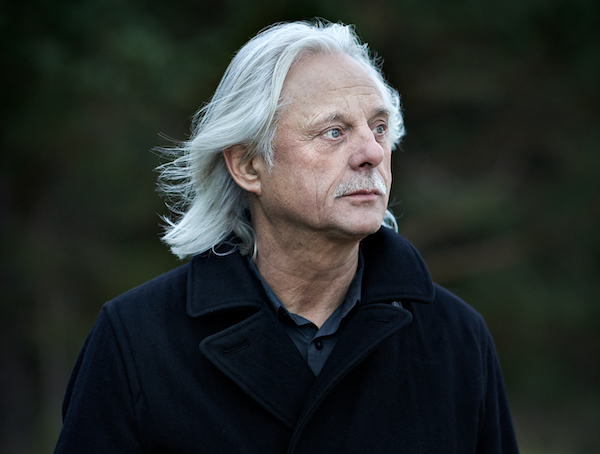

Fifty years ago, Manfred Eicher co-founded Edition of Contemporary Music, better known as ECM, and has issued more than 1,600 titles spanning jazz and classical sounds.

(Photo: Kaupo Kikkas)After playing on guitarist Jacob Young’s 2004 ECM album, Evening Falls, Eicher invited the trumpeter to record his own work. Eick’s ECM debut, The Door, was released in 2008.

Working with Eicher was both exhilarating and a bit nerve-racking. “He’s one of my idols,” Eick said. “I was trying not to think of the history that he has had his hands on, and all that he has meant to me. It took me a couple of albums to really relax. Maybe after we had a few glasses of wine and went out and had dinner, and he came and met my family, he became human.

“That was the biggest challenge for me, personally, just to relax and to trust myself and my own opinions in the context of working with Manfred.” With a laugh, he added, “I would do whatever he told me.”

ECM has done more to disseminate the “Norwegian jazz” sound to other countries—especially the United States—than any other label, beginning in the ’70s.

“My choice of Norwegian musicians was very selective,” Eicher said, citing saxophonist Jan Garbarek as a prime example. “The four players of [Garbarek’s 1970 album] Afric Pepperbird—Jan, [guitarist] Terje Rypdal, [bassist] Arild Andersen, [drummer] Jon Christensen—had a big influence on the music that followed. For a long time, Oslo seemed a good place to record and develop ideas, because it was so far from the center of the jazz scene. And the studio became my home—Talent Studio, and then the first Rainbow Studio, with Jan Erik Kongshaug.”

But if there is a flagship ECM artist, it is Jarrett, whose first ECM title was the 1972 studio solo album Facing You. A few years later, Jarrett recorded his most popular album—also ECM’s most celebrated title: The Köln Concert. The landmark solo piano improvisation opus was recorded on Jan. 24, 1975, at the Opera House in Cologne, Germany. Today, it has sold millions of copies and appeared on many “Best Jazz Albums of All Time” lists.

Jarrett’s ECM discography, upward of 70 titles, chronicles his so-called “American” quartet with Haden, Motian and saxophonist Dewey Redman; his “European” quartet with Garbarek, Christensen and bassist Palle Danielsson; the Standards Trio with drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Gary Peacock, as well as numerous solo works. Among his classical releases are works by Bach, such as The Well-Tempered Clavier and Six Sonatas For Violin And Piano, a collaboration with Michelle Makarski.

“It’s impossible to sum up in a few sentences what Keith and his music have meant to me personally and to ECM as a label over the decades,” Eicher said. “We have been proud to present the full range of his music, which is, by any definition, a unique body of work from a master of spontaneous invention.” He added, “We have a great trust in each other.”

Early on, there were many bases of compatibility. “[Jarrett] was very much into classical music,” Eicher said, “but also the music of Joni Mitchell and Bob Dylan. Early on, I wrote a letter to Keith, before Facing You. I was proposing he make a record with Jack DeJohnette and Gary Peacock.”

For 1976’s Hymns/Spheres, Jarrett improvised on an organ at the Benedictine Abbey in Ottobeuren, Germany. Eicher worked the organ’s many stops: “He was playing and telling me which stops to pull at which times.”

In a 1995 interview (with this writer), Jarrett reflected on ECM’s role in his career: “The ability to find somebody who heard what I was doing and let the format be determined by me, basically, was what I needed. So, if there wasn’t anyone like Manfred—in my case, that’s who there was—I don’t know what would have happened otherwise.

“On the one hand, the story might have been different and I might not have been able to do what I’ve done. On the other hand, I know how early I felt that I was going to be doing something. I just wasn’t sure when. I knew that my work would be of value. I don’t know if I ever would have found the outlet, so in that case, there would have been a horrible difference between the beginning that I did have and the nonbeginning that I might have had.”

One striking recent ECM release was veteran bassist Barre Phillips’ solo project, End To End. (Interestingly, ECM also released Larry Grenadier’s solo bass album The Gleaners on Feb. 15.)

Eicher noted, “I knew Barre already before ECM began and admired his playing. Hearing him together with Dave Holland inside an NDR Workshop project led to [1971’s] Music From Two Basses and a working relationship that extended over half a century.”

While at the FIMAV festival in Victoriaville, Quebec, this year, where he delivered a remarkable solo set, Phillips recounted the origins of End To End. A seasoned solo bass concert performer with a handful of solo bass albums—including his 1984 ECM album, Call Me When You Get There—Phillips approached Eicher about another solo venture.

“For me, it would be some kind of full circle,” Phillips said. “I started so many things with Manfred in the ’70s. I called him up and he said, ‘Yeah, I want to do it tomorrow.’ That surprised me very much, because he’s such a busy man. We made the record. I made the music. He made the record. I have to be clear about that.”

During July’s Moldejazz Festival in Norway, Bill Frisell, 68, sat in his hotel’s lobby, in plain view of the adjacent Romsdal Fjord, recounting his history with ECM. Early on, Frisell earned the sobriquet “ECM house guitarist,” via sideman roles with Garbarek, Weber and others. He recorded three leader albums for ECM in the 1980s before becoming frustrated with creative control issues, later recording for Nonesuch, Savoy and OKeh, and recently signing with Blue Note.

Before a duo concert with bassist Thomas Morgan, Frisell recalled a fateful 1981 gig at Moldejazz with Arild Andersen, which virtually marked the launch of his initial ECM chapter. Three decades later, apart from appearances with Motian, Gavin Bryars, Lee Konitz and Kenny Wheeler, the ECM/Frisell drought ended in 2017, when he and Morgan teamed up for duo album Small Town and its 2019 follow-up, Epistrophy.

Frisell asserted that the catalyst for the recent ECM reunion was New York-based Sarah Humphries, head of the label’s U.S. operations, who was wowed by the duo and determined to release it on the label. “She’s like an angel,” Frisell effused, “a true, incredible mediator, in this world of men trying to be the tough guy. She’s the last person who would ever draw attention to herself.”

Frisell, strongly influenced by ’70s ECM albums, yearns to correct a misconception, explaining, “I have trouble when people say ‘the ECM sound.’ There is something about just being in a big room and there’s space. To me, the ECM sound is also like Columbia records from the early ’60s, or early Paul Bley records. ... Or when Miles played one note and then he waits for five minutes, then hits another one. Or Monk. It’s about waiting for a second [rather than] running your mouth off. It’s not ‘the ECM sound.’ It’s a sensibility about space. Manfred is definitely sensitive to that.

“When you’re on the same wavelength, it’s so amazing to have [Eicher] in the studio, because it’s like his life is on the line. When I’m playing, with every note, I feel like my life is on the line. That’s where he’s at. It’s that intense. You can’t say that about everybody. His commitment to it is really about the music.”

Backstage at July’s Montreal Jazz Festival, Swedish pianist Bobo Stenson, 75, took time before a dazzling, poetic solo concert to reflect on his long ECM connection, dating back to 1971.

Of Eicher, Stenson, who has released several trio albums on ECM, including 2018’s Contra La Indecisión, said: “I would call him a real producer. He really wants to be a part of the process and what is happening. His main thing is to get the creative things out of the musicians. He might come running out into the studio saying, ‘Yeah, keep that. Go on.’ He is very much involved in every production.

“Normally,” Stenson continued, “you record for two days and then you make the whole thing ready on the third day. Everything should be ready by then. On mixing day, [Eicher is] really busy with the sound and also the order [of tracks in the program].”

Another artist deeply connected to ECM and Eicher is influential keyboardist-composer Carla Bley. A stubbornly resourceful artist who launched her own label, WATT, along with a model DIY project, the New Music Distribution Service, Bley recently recalled her pre-DIY days. “I remember asking Manfred, ‘Me and Mike [Mantler] just made this album. Would you like to put it out on your label?’ He wrote back and said, ‘No.’ I remember that,” she said with a chuckle.

According to Bley, in the mid-’70s, NMDS “ended up having to distribute Manfred’s records.” She added, “In those days, I guess none of us had any money. Manfred would sleep on our couch when he was in New York. Everything was pretty relaxed.”

Today, Bley’s WATT releases are part of the ECM catalog. Lately, she has opted to focus on making music—away from the music business aspect—releasing trio albums on ECM, proper, with Eicher as producer. (Her trio bandmates are her life partner, bassist Steve Swallow, and saxophonist Andy Sheppard.) “We figure [Eicher has] got some kind of a magic formula,” she said, “and if we just shut up, he’ll do it for us. ... Manfred is absolutely sure of himself and sure of his reasoning. He knows how he feels about something and he makes sure that’s what he does.”

While ECM’s massive, diverse catalog defies easy description, one recurring thread has been an inward, meditative and even spiritual quality. In some cases, the musical contexts have dealt directly with liturgical music, religious traditions and matters of spirituality, especially in the music of Pärt, Bach and various treatments of Norwegian hymns—and Armenian hymns on pianist/vocalist Areni Agbabian’s latest album, Bloom.

Is ECM, in ways implicit or otherwise, an inherently more spiritually charged enterprise than other record labels of note? Eicher clarified, “It’s ‘spiritual’ in that music addresses matters of the spirit—but it also addresses every other aspect of existence. The ‘mission’ is simply to release music that matters, or what I think matters. Music that has meaning for us and, we hope, for others.”

A final, open-ended question: What’s next?

“Tomorrow,” Eicher said. DB

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…