Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

More Trump-Kennedy Center Cancellations

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

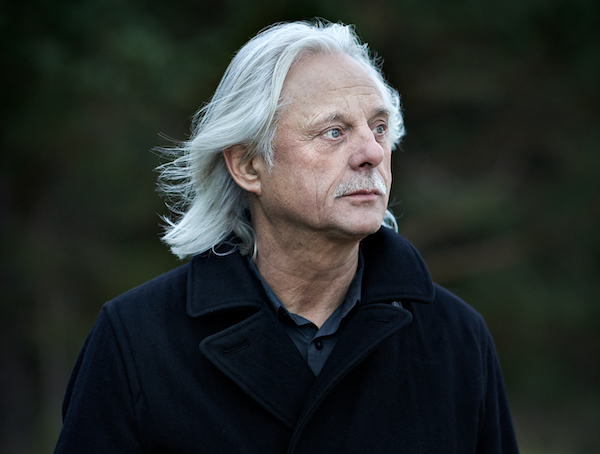

Fifty years ago, Manfred Eicher co-founded Edition of Contemporary Music, better known as ECM, and has issued more than 1,600 titles spanning jazz and classical sounds.

(Photo: Kaupo Kikkas)Acoustics and the recording process have been central ECM concerns. Eicher’s aesthetic involves a sonic landscape of purity, the judicious use of silence and an insistence on live tracking rather than excessive takes, overdubbing or other production trickery.

Eicher’s studio techniques and his malleable “producer” role entail the critical art of “attentive listening,” paying close attention to details and the structure of the musical experience.

“I believe in going with a plan,” he said, “but also being open to whatever might happen unexpectedly in the studio, in the improvisational process. Sometimes, you have to stop and start again, if it’s not coming together or working.

“Each project brings its own demands, such as whether to use a studio with isolation for the musicians or to put them all in the same room, or whether to use a studio at all—compared to, say, a church, as we have done many times with the New Series projects.”

Key sonic collaborators have included such frequently called-upon engineers as Jan Erik Kongshaug in Oslo, Grammy winner James Farber in New York and others. “Together,” Eicher explained, “we worked on developing a sound, and an appreciation of space and silence. We were looking for a sound that was transparent, detailed and lucid.”

Further along in the creative process, Eicher emphasizes the importance of sequencing and shaping the final program. “It’s like film editing,” he said, “telling a story and giving a rhythm to a project.”

An avid cineaste who co-directed the 1992 film Holozän and has worked with iconoclastic director Jean-Luc Godard, Eicher has also cited his admiration for French filmmaker Robert Bresson.

Eicher’s reverence for storytelling helps explain why the album concept is still so important to him, regardless of the format. ECM finally joined the streaming revolution in November 2017, easing a once-firm disinclination to break up an album’s continuity. “Young people don’t understand the power of the album,” Eicher said ruefully, “which is too bad. An album is like a film or a play, presented in a certain way, with an overall sense of rhythm, dynamics and a story being told.”

Back in Munich, ECM’s export manager Heino Freiberg—part of the team for 30 years—was in his office, laying out the chronology of ECM’s technology and platform history, moving from vinyl to CDs, and then, eventually, to digital streaming on platforms like Spotify.

“ECM has been trend-setting in many fields,” Freiberg said, “but in this very special case [of streaming], we followed a little bit.”

The album format, Freiberg said, “remains important—the order of how you present the music, but also, from the very beginning, how to present it, graphically. [Eicher] wanted to have nice packaging and not any kind of short-minded artist photo or instrument. Manfred introduced typography, photography and painting, and this was a way to consider this as an artifact.”

One recent ECM “artifact” of note is the Iyer-Taborn duo’s The Transitory Poems. The pair sat down with DownBeat at ECM’s New York office the day after their high-profile Winter Jazzfest concert. They belong to a coterie of New York-based pianists, including Ethan Iverson and David Virelles, who have become part of the ECM roster in the 21st century.

These two, though, aren’t tethered to “a stylistic thing,” according to Taborn. “It’s just very personal approaches, and I think [Eicher] got excited by that.”

Iyer added, “It doesn’t feel like any one of us is a marginal outlier. Actually, we’re all outliers, a group of nonconformists.”

As sidemen, Iyer and Taborn made their ECM recording debuts with saxophonist and Art Ensemble of Chicago co-founder Roscoe Mitchell—Taborn on Nine To Get Ready (recorded in 1997) and both pianists on Far Side (recorded in 2007). Their debuts as ECM leaders arrived with Taborn’s 2011 solo album, Avenging Angel, and Iyer’s 2014 album Mutations. Both have since released ECM albums in varied contexts and idioms.

Iyer appreciates the label’s broad scope: “Given the fact that [trumpeter] Lester Bowie’s Avant Pop, [tabla player] Zakir Hussain’s album Making Music, and [pianist] András Schiff playing Bach exist under one umbrella, there’s nothing wrong with anything that we propose here. We have to keep reminding ourselves that this is a vast spectrum of music.”

Iyer and Taborn’s connections to Mitchell reinforce ECM’s many links to the Art Ensemble of Chicago and the Association for Advancement of Creative Musicians. Eicher noted, “We recorded musicians from the AACM from the early days of ECM onwards. Anthony Braxton plays on [saxophonist] Marion Brown’s Afternoon Of A Georgia Faun [1970], the fourth ECM album, and would soon reappear on Circle’s Paris Concert [1972] and Dave Holland’s Conference Of The Birds [1973].

“As a bassist, I played in 1970 with Leo Smith and Marion Brown in their Creative Improvisation Ensemble [documented by Theo Kotulla in his film See the Music]. And I still work with Wadada: Next year we’ll put out a new album by him.”

On the ECM-dense January weekend in New York, trumpeter Mathias Eick, 40, spoke to DownBeat about his ECM path. Eick is one of the most popular of ECM’s more recent Norwegian contingent—a list that includes saxophonist Trygve Seim, trumpeter Arve Henriksen and keyboardist Christian Wallumrød.

Belá Fleck during an interview with Fredrika Whitfield on CNN.

Jan 13, 2026 2:09 PM

The fallout from the renaming of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to include President Donald…

Peplowski first came to prominence in legacy swing bands, including the final iteration of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, before beginning a solo career in the late 1980s.

Feb 3, 2026 12:10 AM

Ken Peplowski, a clarinetist and tenor saxophonist who straddled the worlds of traditional and modern jazz, died Feb. 2…

The success of Oregon’s first album, 1971’s Music Of Another Present Era, allowed Towner to establish a solo career.

Jan 19, 2026 5:02 PM

Ralph Towner, a guitarist and composer who blended multiple genres, including jazz — and throughout them all remained…

Rico’s Anti-Microbial Instrument Swab

Jan 19, 2026 2:48 PM

With this year’s NAMM Show right around the corner, we can look forward to plenty of new and innovative instruments…

Richie Beirach was particularly renowned for his approach to chromatic harmony, which he used to improvise reharmonizations of originals and standards.

Jan 27, 2026 11:19 AM

Richie Beirach, a pianist and composer who channeled a knowledge of modern classical music into his jazz practice,…