Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Saxophonist, Sonic Explorer Casey Benjamin Dies at 45

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

Joshua Redman’s current quartet first convened in 1998.

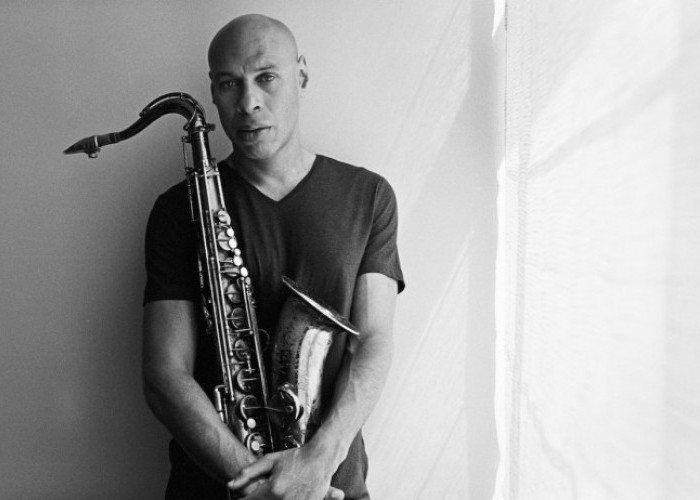

(Photo: Michael Wilson)When DownBeat contacted Joshua Redman about an interview, the saxophonist and Berkeley, California, resident agreed to meet at a particularly appropriate location.

Located in the East Bay city’s dynamic downtown arts district, Freight & Salvage Coffeehouse is a nonprofit community arts organization that produces concerts and hosts music classes. Its neighbors include the California Jazz Conservatory and Berkeley Rep, which presented pre-Broadway runs of American Idiot and What the Constitution Means to Me.

The athletic Redman, 50, settled into a Freight & Salvage practice room for a conversation about Come What May (Nonesuch), the new album by his longstanding quartet with pianist Aaron Goldberg, bassist Reuben Rogers and drummer Greg Hutchinson. Featuring seven Redman originals, it’s the group’s third album.

The son of Texas tenor Dewey Redman (1931–2006), Joshua rose to fame as a summa cum laude Harvard graduate who won the 1991 Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz International Saxophone Competition (ahead of Eric Alexander and Chris Potter) and then eschewed Yale Law School to pursue music. Since then, he’s gigged and often recorded in solo, duo, trio, quartet and quintet settings. Redman’s live album Nearness (Nonesuch)—recorded with pianist Brad Mehldau and released in 2016—won the duo glowing reviews.

Nowadays, the husband and father to two school-age children is enjoying the second act of his career. In addition to his quartet, he’s worked in recent years with The Bad Plus and as a member of the groups James Farm (with pianist Aaron Parks, bassist Matt Penman and drummer Eric Harland) and Still Dreaming (with cornetist Ron Miles, bassist Scott Colley and drummer Brian Blade).

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

For several years, you’ve recorded and toured as part of three saxophone quartets, as well as the band Still Dreaming. What’s the experience been like to move from project to project?

What happened to my focus? [laughs] I guess I’m in a phase where I’ve been involved in a lot of ongoing projects, ongoing bands. Definitely for the first 10 or more years that I was doing this professionally, I would only have one band at a time. I think, at that time, I only felt comfortable kind of focusing on just one thing.

All of these projects are now continual founts of inspiration for me. It can be a little musically disorienting at times. But in general, it works out well. And I gain so much from playing with these different combinations of amazing musicians.

Because your quartet hasn’t released an album since the turn of the century, many people might not realize how long the group has been together.

We started playing regularly together as a quartet around 1998 through 2001. That was my main working group. And we started working together again in 2013. At that time, I was writing a lot of new quartet music, and in the past five years we’ve built up a pretty big repertoire of stuff that we played together back in the late ’90s, plus standards that we all love and new tunes that I’ve written.

Our collective history goes even further back: Reuben and Aaron have been playing together since Reuben moved to Boston from St. Thomas in 1992. And I’ve been playing with Greg for basically that long. I haven’t done the math or done the count, but I’d venture to say I’ve probably done more gigs and logged more hours off and on the bandstand with those three than with anyone else over the years except maybe Brian Blade.

How would you characterize this band?

There’s no substitute for the understanding and the empathy and the trust that you build up, that you earn, over two-plus decades of playing with the same musicians. It’s a collaborative ethos where we do what’s right for the music and not for our own individual agendas.

One of the things that’s so great about playing with those guys is, I know that whatever I bring in—no matter how convoluted it is, or how overwritten it is, or how messy it is or even how bad it is—they’ll find the best music within it and bring that out. Those guys really know how to make music feel good. They really prioritize that sense of rhythmic infectiousness, that sense of groove.

Do you compose with specific bands in mind?

It depends. Having the family and being on the road so much, I find it’s harder for me to get into that space where I’m ready to write. So, I go through longer periods where I’m not writing now. Then sometimes when I’m writing, I just have to kind of force myself to just write something.

I can’t even think, “Oh, I’m going to write a tune for James Farm. Or I’m going to write a tune for Still Dreaming. Or a tune for the quartet.” I just have to start writing anything. It’s just a matter of pen to paper, or mouse-click to Sibelius note-entry, or finger to piano.

Then I allow whatever the creative process is to take shape and unfold, and I might end up with a tune. And at a certain point, I might realize, “This sounds like a tune that would work for quartet,” or “This sounds like a tune that’s better without piano—perfect for Still Dreaming.”

And maybe some of the stuff I would write for James Farm might be more complex in terms of time signatures. That’s something we like to play with as a band. And it may be more structured, compositionally.

Ambrose Akinmusire, a fellow Berkeley High School alum, said your 1995 album, Spirit Of The Moment, recorded at the Village Vanguard, made a big impression on him. Have you adjusted to the notion of being influential?

I feel guilty. And I want to apologize, because I don’t see how I could be anything but a bad influence! [laughs]

But it’s weird: I just turned 50, so I officially can no longer be called a “young lion.” I couldn’t, really, for the past 25 years. But there’s no question, I’m not young anymore.

I’ve been lucky that I’ve been able to do [music] seriously since ’91. You do this for long enough and play with enough musicians and make enough records, and I suppose eventually some people hear your music. And a lot of them are younger. But I’m just very focused on trying to play honest and creative now. So, the thought of something “cringey,” as my son would say, I did 20 years ago being at all influential is strange.

Benjamin possessed a fluid, round sound on the alto saxophone, and he was often most recognizable by the layers of electronic effects that he put onto the instrument.

Apr 2, 2024 12:59 PM

Casey Benjamin, the alto saxophonist, vocalist, keyboardist and producer who stamped his distinctive sounds on the…

“He’s constructing intelligent musical sentences that connect seamlessly, which is the most important part of linear playing,” Charles McPherson said of alto saxophonist Sonny Red.

Feb 27, 2024 1:40 PM

“I might not have felt this way 30 to 40 years ago, but I’ve reached a point where I can hear value in what people…

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935–2024) followed in the tradition of drummer Kenny Clarke, his idol.

Apr 5, 2024 10:28 AM

Albert “Tootie” Heath, a drummer of impeccable taste and time who was the youngest of three jazz-legend brothers…

“Both of us are quite grounded in the craft, the tradition and the harmonic sense,” Rosenwinkel said of his experience playing with Allen. “Yet I felt we shared something mystical as well.”

Mar 12, 2024 11:42 AM

“There are a few musicians you hear where, as somebody once said, the molecules in the room change. Geri was one of…

Henry Threadgill performs with Zooid at Big Ears in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Apr 9, 2024 11:30 AM

Big Ears, the annual four-day music celebration that first took place in 2009 in Knoxville, Tennessee, could well be…