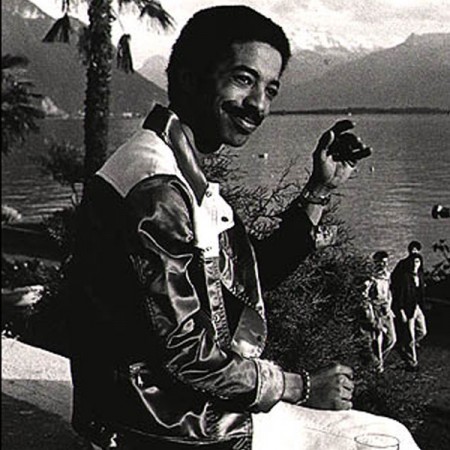

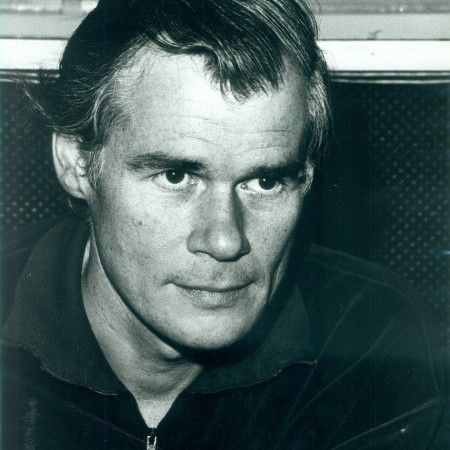

“One of the reasons that we appear to be not so popular with the so-called ‘jazz’ public is because they expect Miles to be doing something he did five, 10 years ago,” said drummer Al Foster. “This current band is going in another direction, and I think that it’s wrong to put the music down simply because it differs from yesterday. … My favorite musicians today are Miles, Sonny Rollins and Sly Stone. I love the variety available to us. You lose something when you restrict yourself.”

(Photo: DownBeat Archive)

“To see him is still an experience,” Andy Bey said of Jimmy Scott. “Life force. Still blues-based, still a lot of soul.”

(Photo: Steven Sussman)

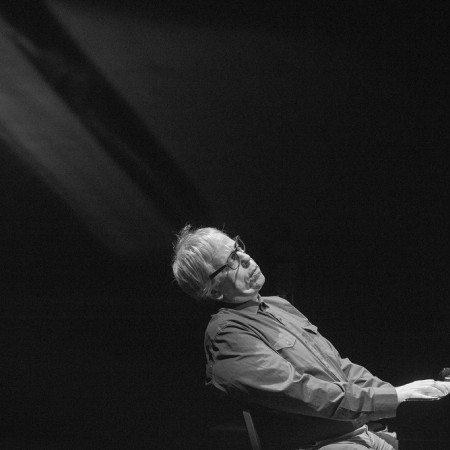

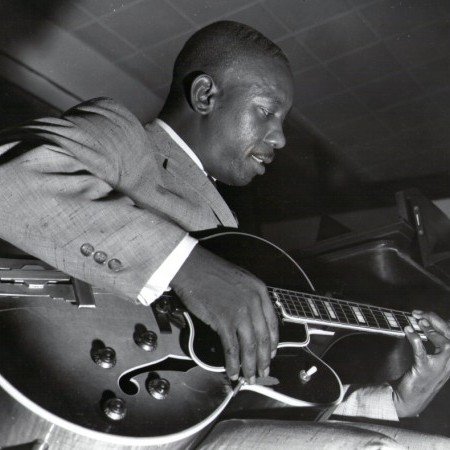

“I heard Lou Donaldson for the first time, and that down-home feeling of his was a gas,” said Bunky Green about one of his early influences.

(Photo: DownBeat Archive)

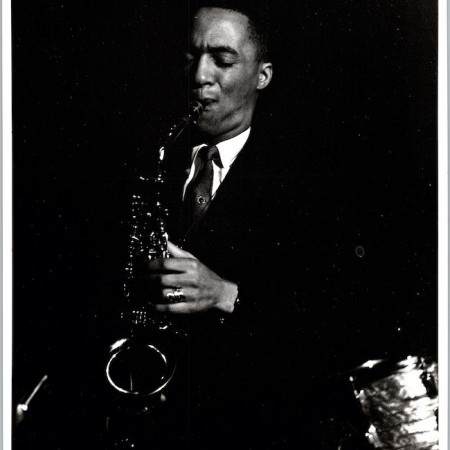

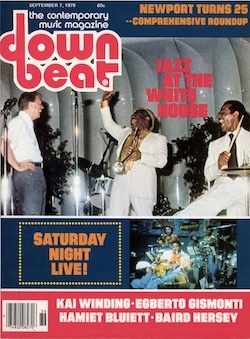

The cover image of DownBeat’s Sept. 7, 1978, issue, which featured in-depth coverage of President Jimmy Carter’s jazz picnic party on the White House’s South Lawn. The historic gathering honored and was honored by a history of jazz that embraced everything from ragtime through the avant garde.

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)

“If you never suffered, you can’t play the blues,” says Lou Donaldson.

(Photo: Tomas Ovalle)

The candidate and his crew, from left, Kenny Barron, James Moody, Rudy Collins, Dizzy Gillespie, Chris White and Shelly Manne.

(Photo: Robert Skeetz)

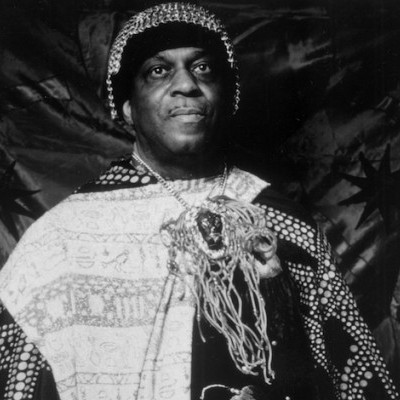

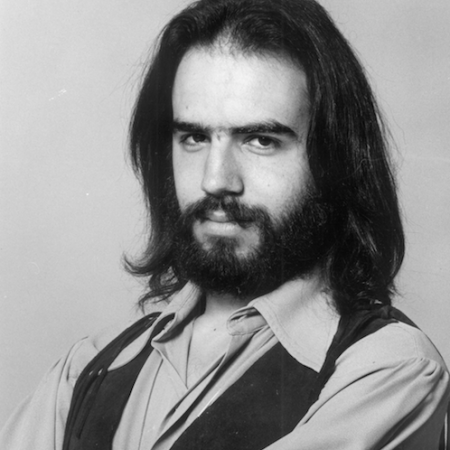

Albert Ayler

“The thing about New Orleans jazz,” Don broke in, “is the feeling it communicated that something was about to happen, and it was going to be good.”

“Yes,” Albert said, “and we’re trying to do for now what people like Louis Armstrong did at the beginning. Their music was a rejoicing. And it was beauty that was going to happen. As it was at the beginning, so will it be at the end.”

I asked the brothers how they would advise people to listen to their music.

“One way not to,” Don said, “is to focus on the notes and stuff like that. Instead, try to move your imagination toward the sound. It’s a matter of following the sound.”

“You have to relate sound to sound inside the music,” Albert said. “I mean you have to try to listen to everything together.”

“Follow the sound,” Don repeated, “the pitches, the colors. You have to watch them move.”

“This music is good for the mind,” Albert continued. “It frees the mind. If you just listen, you find out more about yourself.

“It’s really free, spiritual music, not just free music. And as for playing it, other musicians worry about what they’re playing. But we’re listening to each other. Many of the others are not playing together, and so they produce noise. It’s screaming, it’s neo-avant-garde music. But we are trying to rejuvenate that old New Orleans feeling that music can be played collectively and with free form. Each person finds his own form.

“Why,” I asked, “did bop seem too constricting to you?”

“For me,” Albert said, “it was like humming along with Mitch Miller. It was too simple. I’m an artist. I’ve lived more than I can express in bop terms. Why should I hold back the feeling of my life, of being raised in the ghetto of America? It’s a new truth now. And there have to be new ways of expressing that truth. And, as I said, I believe music can change people. When bop came, people acted differently than they had before. Our music should be able to remove frustration, to enable people to act more freely, to think more freely.

“You see, everyone is screaming ‘Freedom,’ but mentally, everyone is under a great strain. But now the truth is marching in, as it once marched back in New Orleans. And that truth is that there must be peace and joy on earth. Music really is the universal language, and that’s why it can be such a force. Words, after all, are only music.

“I’m encouraged about the music to come,” Albert said. “There are musicians all over the States who are ready to play free spiritual music. You’ve got to get ready for the truth, because it’s going to happen. And listen to Coltrane and Pharaoh Sanders. They’re playing free now. We need all the help we can get. That Ascension is beautiful! Consider Coltrane. There’s one of the older guys who was playing bebop but who can feel the spirit of what’s happening now. He’s trying to reach another peace level. This is a beautiful person, a highly spiritual brother. Imagine being able in one lifetime to move from the kind of peace he found in bebop to a new peace.” DB

T.S. Monk at home

(Photo: Michael Weintrob)So what happened was the Japanese came up with a very, very good marketing philosophy. What they would do is when you had all these jazz musicians come in, when you got off the plane in Tokyo, they’d put a Seiko watch on your wrist. They’d put a Sony miniature TV in your hand. And they’d hang a Nikon camera around your neck. So, I go to the airport and here comes Thelonious and Dizzy and these cats. And Dizzy had this Nikon camera—this was a $1,000 camera in 1962–’63. Dizzy looked at me. I’m saying, “Hi, Dad. Hi, Dizzy.” Hi to everybody. He looks at me and says, “Monk, the kid like cameras?” He just took it off his neck and put it around my neck—a $1,000 camera. And I’ve been into photography ever since.

I WAS ALLOWED to run around like a little maniac and be a kid. I remember one night, I don’t even know where we were, but Art was there and Max was there and Sonny and a whole lot of cats. I think they might have come down to hear Thelonious. And I’m running around the room doing my little thing. And I remember Thelonious saying, “Hey, Coltrane.” And Coltrane said, “What, Monk?” And Thelonious said, “You see? That’s my son there. You know he’s automatically hip.” [laughs] Now, myself, I was embarrassed. I didn’t know what this was about. First of all, how am I automatically hip?

WHAT I REALIZED years later was the major self-esteem building that he was doing on me. I didn’t know it at the time because it seemed so off-the-wall. But he was telling me, “You are my son. And I’m very hip. And you are automatically hip because you are my son. And John Coltrane, dig him.”

DESPITE WHAT YOU MIGHT HAVE READ about his aloofness, Thelonious was probably the most accessible of all the giants in jazz that we have ever had. Thelonious insisted on our address and telephone number being in the phone book his entire life. He didn’t want no unlisted number. Of course he had me and my sister and my mother to answer the phone for him. So, he never had to deal with the telephone himself. But he was very, very regular in a lot of ways.

ONE OF THE REASONS that I believe I was able to garner support during the first years for the Monk Institute was that I had an actual personal relationship with those guys—with Clark Terry, with Jimmy Heath, with Max Roach, with Billy Taylor. I knew them personally, so I was able to go to them personally and say, “Hey, I’m going to start this organization called the Monk Institute of Jazz. Would you help me out?” I don’t think if Thelonious didn’t have me on his knee, hanging around all the time, I would have been able to do it, or it wouldn’t have been as easy, because I wouldn’t have those personal relationships. You know what was amazing? They all bought my father’s rap. I was automatically hip. [laughs] So, when I went to them, there was no resistance at all. They all said, “This is Monk’s son. He’s automatically hip. We’re ready to get down. We’re ready to go.” It made it a lot of fun.

AT 15, I WAS GETTING home from school, and I just broke down. I said, “Dad, I think I want to play the drums. I think I really want to play the drums.” And he said, “Oh, really?” And this is no lie. It was one of the few times I actually saw my father pick up the phone and call somebody. He said, “Art, look, Toot needs some drums.” Like three days later, I had a set of drums from Art Blakey. He put the phone down from Art. He picked up the phone again. And he dialed a number. He said, “Max Roach.” He always called him “Max Roach.” He never called him “Max.” He said, “Max Roach, you are the greatest drummer in the world, and the kid wants to play the drums. I’m sending him to your house.” [laughs] So, he sent me to Max. And then, he didn’t say one word. That’s at 15. At 19, I discover who he is, and he still hasn’t said a damned word to me about what I’m playing!

The next year, when I was 20, he just comes sauntering through the house and asks, “Are you ready to play?” And two days later, I was on the bandstand. I was in his band. It went just like that.

I JUST STARTED PLAYING with the band, but I’d known from observing him that he wouldn’t say anything. I never heard him say two good words about Charlie Rouse, either. So, I didn’t feel bad. Thelonious was from that generation that, you know, you were supposed to be playing all that hip stuff. There was something to say if you weren’t, but if you were, there really wasn’t anything to say because that’s what we do.

ONE NIGHT, we were playing at the Village Vanguard. The line was around the block. The show was packed. We hit it. Everybody went crazy, standing ovations. And during that performance I did something. I turned the beat around. Now, everybody knows that jazz is about recovery. It’s all about the recovery. If you recover correctly, then no mistake took place. So, I recovered my butt off, right? So, I’m feeling groovy. I’m standing in the kitchen. I’m signing autographs. I’m grinning.

And I felt this presence ease up on me. So, Thelonious eases up next to me and leans down, while I’m signing autographs, and he says, “Stop f’ing up the music, man.” I mean, for real. He didn’t say “f’ing”—it was the full monty. And I was stunned. The abject lesson was not that I made a mistake; the abject lesson was in accountability. Because, despite the applause, despite the accolades, I didn’t come up to the bandstand and say, “Hey guys, I’m sorry I jammed us up.” I acted like it never happened. I was completely awash in all this glorification.

At 25 years old, bassist Esperanza Spalding wasn’t overly concerned with marketability.

(Photo: Sandrine Lee/Montuno Productions)The next morning, Spalding is speechless—almost. “Anything I could say would not do justice,” she says when asked what it’s like to play with Tyner. But hardly ever at a loss for words, Spalding says that it wasn’t a case of intimidation the first time she played with him, but more self-consciousness and even a sense of insecurity. She recalls that the summer before the Yoshi’s gig was dreamed up, she and her longtime pianist Leo Genovese had gotten into a total Tyner-zone over the course of two month-long gigs.

“So, McCoy was already in the air,” she says. “We listened to hours and hours of his music—solo recordings, live albums, quartets. We’d be driving for six hours through Italy and taking about McCoy the whole way. So, when the Yoshi’s week came up, I knew all of his music, so I didn’t have to prep as much. But, as a bass player, I knew it was going to be difficult because McCoy plays the bass and the drums at the same time on the piano. At first, that was a challenge for me, figuring how I could offer him the most with my bass, but by the end of the week at Yoshi’s, I felt less idiotic. We were all totally engaged.”

Spalding has had a love affair with music since she was very young. She was home-schooled for a stretch after a childhood illness and dropped out of the conventional setting of high school to pursue music. She took her GED, enrolled in the music program at Portland State University and entered Berklee on a scholarship thanks to her bass prowess. She graduated a year early in 2005 at the age of 20, and with much fanfare was immediately hired to teach in the bass department there. (She’s since terminated her pact with Berklee, partly because she’s gotten so busy, partly because she had qualms with the classes the school administration wanted her to teach.)

By that time, she had established herself as a side player with such notables as Lee Konitz and Patti Austin, as well as a bandleader in her own right, which led to her recording a demo in April 2005 that was picked up by Ayva. A year later Junjo was issued in the States, at which time Spalding said, “My music has come so far from when we recorded it. It’s all been a trip. It seems like every six months my music evolves. As I meet different musicians in new circles, they influence me and change my sound.”

A nine-song collection of buoyant originals and sprightly covers, Junjo featured Cuban pianist Aruán Ortiz and Mela. In the liner notes, Spalding wrote: “You are my people, and I hope to make a dozen more CDs with you as we grow together musically and personally.” As it turned out, that dream proved to be wishful thinking. By the time it finally saw the light of day in the States, she laughed at the liners and said, “Already we’ve all become too busy. I’m glad we had the chance to take a picture, and I hope to take more. But they’re off and I’m on to other stuff, too.”

In 2007, Umbria creative director Carlo Pagnotta caught her at the Jazz Standard in New York playing in a trio comprising guitarists Romero Lubamba and Russell Malone. “I wanted to have her come to Umbria with them,” Pagnotta said, “but she insisted on bringing her own band.”

At the festival, Spalding proved to be a revelation to the audiences at the Oratorio Santa Cecilia, where she performed three days with her trio of Genovese on piano and Lynden Rochelle on drums. She was a sparkplug who danced with her bass as she scatted and sang through a mixed set of standards (a grooving “Autumn Leaves” and a funky, upbeat take on “Body And Soul”) and originals such as “Winter Sun,” a samba-tinged tune with a funk-rock beat that she retitled “Summer Sun” for the occasion.

As for the expansive range of her music, she said, “Everyone wonders, why did you go to jazz when you’re interested in so much else? For us young jazz musicians, it’s how we learn music. It’s like reading a sacred text in Greek. So, we study and learn more and more, but our hearts are into a mishmash of different sounds.”

At her Umbria performance, Spalding was as likely to explode into a patch of vocalese as to solo using her bass to sound like a horn. “I can’t help it,” she said afterwards. “I always try to tone down my dancing with the bass. I think, I must look like an idiot, but then I bust out and can’t control it.”

In regard to her Heads Up debut, Spalding upped the ante on her vocals and plowed deep grooves with her bass. It scored top of class, as far as selling the most CDs internationally for a new jazz artist in 2008.

After the popularity of Esperanza, Chamber Music Society is decidedly an album that’s coming in from left field. Inspired by the Chamber Music Society of Oregon (in which she played violin for 10 years), Spalding decided to create a modern image of a chamber group with string trio arrangements complementing her own originals that are infused with pop, folk and jazz. Genovese is on board, as well as drummer Terri Lyne Carrington.

Spalding credits her Barcelona-based management, Montuno Productions, with giving her free license to pursue her latest musical vision. “They were the first people to approach me when I was just starting,” she says. “They loved my music, and I’ve loved working with them. Sometimes I forget how blessed I am when I think of young artists whose managers are not really on their team. I told Montuno that I was making a decision that might not seem to make much business sense, but they’d just have to respect me.”

Spalding didn’t have a fully developed game plan for Chamber Music Society. It evolved slowly and came into focus with the help of Goldstein. “I wanted to work with Gil because of his enthusiasm,” she says. “This genius master was so into my music that he was willing to go into it and make it better.”

Spalding, says Goldstein with admiration, is “always reaching for something new every time she performs. She puts a face on every note. She’s become more refined as a player. She’s going deeper.”

Goldstein explains how he got involved in Spalding’s project: “It’s not luck or an accident. It’s more like I attract things that are suited to me. I have a distrust of things that are won through politics or positioning, and feel more blessed and in sync when things unfold in an organic way.”

Spalding showed Goldstein three Chamber Music Society pieces she had arranged. Goldstein attended a Spalding show with pianist Adam Goldberg, vocalist Gretchen Parlato and three string players. “It was an early presentation of her chamber music project,” he says. “But I didn’t know what I could bring to it to make it better. I wasn’t sold on the three strings and suggested that we bring in a couple of woodwinds. Espe immediately said no woodwinds. I said we may need some more colors in the music, so we decided to bring in extra singing voices. As it turned out, Espe sang in such a pure way that she sounds like a woodwind.”

While she’s received a lot of attention for her bass playing (she won this year’s DownBeat Critics Poll for Rising Star, Acoustic Bass), Spalding also has improved immensely as a singer, showcased on wordless and lyrical parts throughout Chamber Music Society. Early on, she was best known as a terrific bassist in motion to greater heights, but then she began to slip in vocal numbers among the instrumentals.

She’s been intent on that ever since, especially on Chamber Music Society.

Spalding downplays the notion that she’s doing anything new or special as a bassist who also sings. “I never thought about singing,” she says. “I didn’t really care, because it came easy to me. But in the last couple of years, I decided to cultivate that. But I didn’t know what I didn’t know. I was singing by ear and not worrying about how it sounded.”

Spalding’s first self-taught vocal exercise was singing Michael Brecker’s saxophone solo on “The Sorcerer” from his Directions In Music. She recorded herself and became dismayed when she played it back. “What I thought was happening was not really happening,” she says. “What I was hearing in my head—the timbres, the different sounds, the textures—was not happening. I had to learn how to get that, how to articulate and come to the understanding of the mechanism of the instrument like I have with the bass.” She began to listen to and study singers like Betty Carter, Abbey Lincoln and Nnenna Freelon to find out what was lacking in her own vocals.

Goldstein has seen the progress and goes so far as to say that Spalding is one of the best jazz singers on the scene today. “She’s a real jazz vocalist like Abbey or Betty,” he says, then adds, “not like an Ella or Sarah who were more populous. Espe is so versatile, running the gamut from great r&b to Stevie Wonder pop, and sings with the most personality. You hear half a note and you know it’s her.”

He’s also amazed at how she plays bass and sings. “I can’t think of another jazz singer who can sing the melody and comp with the bass notes for herself the way she does,” Goldstein says. “It’s singing the melody and anchoring the rhythm. The world could collapse around her, or she could be playing with the worst drummer, and she would still protect the rhythm like a soccer goalie.”

Parlato, a good friend who has appeared on Spalding’s last two albums (including their show-stopping duet on Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Inutile Paisagem” on Chamber Music Society), says that Spalding’s singing has become “profound and versatile.” It helps, she says, that Spalding studied instrumental music first. “She’s singing at such an advanced level. She’s developed a very unique sound with her tone and texture that immediately hits you. It gives me goose bumps. She’s very precise, perfectly in tune and takes big risks. Her dynamics are so wide. She’s doing everything the right way. She’s causing a scene by just being herself as a total person.”

When reminded of her telling me three years ago that wonderful things happen as a byproduct of the natural evolution of a musician who’s in motion, Spalding says, “Yes, it’s all about the process. That’s getting reaffirmed over and over. The things I forget the quickest are the events. But what I don’t forget is being some place and grabbing a chunk of insight from another musician. It kicks my butt into a new direction.”

As for the future, Spalding, who splits time between Austin, Texas, and New York’s Greenwich Village, is already conceptually working on her next album, Radio Music Society, which she initially described as a funk, hip-hop, rock excursion. That’s all changed now, as she’s been on the road experimenting with the tunes she’s written so far. “It’s about putting elements of our own music onto the radio,” she explains. “It’s about playing songs that should be on the radio but haven’t been meddled with for the sake of getting on the radio. We’ve been doing some of these songs live and people are freaking out. They love them.” Knowing Spalding, their shapes are bound to change even more when she and her band hit the studio in November.

The final question of our interview gives Spalding pause. She’s a fluid talker, who moves from topic to topic with gleeful ease. But when asked to describe herself in six words, she stops in her tracks. The wheels are turning, but after long thought, she settles on her phrase. It’s not perfect, she says, but it’ll do: “Striving to achieve full human potential.”

It’s an excellent summation of what lies ahead—steady and grooving and determined as she goes. DB

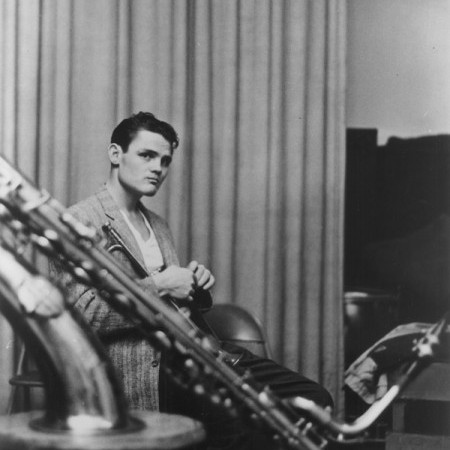

In addition to making significant contributions to the jazz canon’s batch of standards, saxophonist Benny Golson appeared in a pair of films and was photographed in “A Great Day In Harlem.”

(Photo: Oliver Rossberg)Jazz was a young music when Golson stood on that Harlem doorstep sometime in July or August 1958. (The precise date has been lost.) Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor were barely on the radar. The first jazz record was only 41 years old, about the same span of time that separates us from the death of John Coltrane today.

Few jazz musicians of importance had marked a 60th birthday yet, not even Louis Armstrong. The two oldest players in the Esquire photo were Zutty Singleton, 60, and Sonny Greer, 62. Old age in jazz was still uncharted territory in 1958. No one yet knew what a 65-, 70- or 80-year-old trumpet or saxophone player might sound like. Bunk Johnson, perhaps?

“The mind doesn’t change,” Golson observed with some experience in the matter of age. “Only the body. Sometimes the mind makes appointments the body can’t keep. Arthritis, feeling tired, things like that. When you’re young, you’re always ready to go. But the thinking doesn’t change. In fact, if one has talent, it’s like good wine. You add things to it. It gets better. You renew yourself. You take the older things, push them to one side and make room for the newer. Creativity never retires, unless you give up. I wake up every morning at this age and intuitively think, ‘What can I do better today than I did yesterday? What can I discover today? What things are awaiting my discovery?’ Enough is never enough. You want to get from here to there, then you get there and you want to go somewhere else.”

Golson’s uncle was a bartender at Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem. One of Golson’s earliest memories is being taken to the now-legendary site of the earliest bop jam sessions and seeing the house band with Thelonious Monk, Joe Guy and Kenny Clarke. “I was 11 and didn’t know what the heck it was all about,” he admitted. “But Sugar Ray Robinson was there and my uncle introduced me to him.”

A conversation with Golson doesn’t go long before the subject of another of his childhood associations—John Coltrane—comes up. The two knew each other as boys in Philadelphia, and in some ways, Golson seems to measure himself against Coltrane, even though they took vastly different paths. Perhaps it’s because they started at the same time and in the same place.

“Look at my friend John Coltrane,” he said. “He was great, but he wanted to go farther. I haven’t gotten there yet. Where is there? Wherever it is, we want to get there as soon as we can.”

Where they began as adolescents, though, was the height of the swing era in 1940. Golson was 12, Coltrane 14. When they turned on the radio, they heard anyone from Jan Savitt to Count Basie playing live music. “You know who my favorite band was then?” Golson asked rhetorically. “Glenn Miller. And I loved [tenor saxophonist and singer] Tex Beneke with that Southern drawl he would sing. I loved that. ‘Moonlight Serenade’ and the movies, Sun Valley Serenade and Orchestra Wives.”

Golson might have loved Miller and Beneke, but he didn’t imitate them. His epiphany came at 14 in the Earle Theater. “It was the first time I ever saw a band live,” he said, “and it was Lionel Hampton. When the curtain opened I was bedazzled. The bright lights were shining on these gold instruments. The music was like a hand reaching out and grabbing me. Then Arnett Cobb stepped out from the reed section to the edge of the stage, and, lo and behold, a mike came up from the stage floor. When he started to play, the piano paled. I wanted a sax. We were just getting off of welfare, but I thought I could get one at a pawn shop. One day [my mom] brought a brand new one home, and wow. That’s when it all started.

“I was listening to records,” he continued. “Coltrane and I were doing the same thing. There were no school jazz programs. Then right in the middle of all this, along come Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. Coltrane and I are trying to learn the traditional stuff, and not very good at it. Then this new stuff comes out. So, we’re trying to pick up on this new music before we’ve learned the old stuff. We had a kind of oath of determination to try to imbibe this music and make it part of our psyche.”

Golson and Coltrane were like two peas in a pod then. Golson listened to Coleman Hawkins and Ben Webster. Coltrane played alto and loved Johnny Hodges. “But he was always a little ahead of the rest of us,” Golson said. “When we got to where he was, he was always somewhere else. He had a penchant for that—to always reach. But his reach never exceeded his grasp. He always got to it.”

Was it a place Golson might have followed? “Truthfully,” he said, “I wouldn’t have known what I was doing. He was somewhere else then, and I was not in that place.”

Does Golson believe that Coltrane is being remembered for the right reasons today? He asked what I meant. Is it his music, I explained, or the quasi-religious and mystical dimensions of his persona that surfaced on A Love Supreme? What other musician, after all, defined his music in such overtly spiritual terms that it produced a San Francisco church in his name? (Golson himself crafted an impressive orchestration of A Love Supreme in the ’90s.)

“I don’t think [he] would have been a part of that,” Golson said. “I’m sure he would have shivered at that prospect of a Coltrane church. He was really not religious when I knew him. Whatever happened in his search happened later when we were no longer together. He was like Picasso, in that he went through many periods; many styles. He was always changing and evolving into something, searching.”

Perhaps because Golson was once such a close witness to Coltrane’s processes, he respects his outcomes even if he cannot entirely embrace them. Coltrane may have ended in the tangle of the free-jazz movement, but Golson had seen him master so much.

He’s decidedly less sympathetic to others associated with the music, though. He won’t mention any names, lest he might harm a fellow musician. Yet he makes no secret of his views on the larger free-jazz musicology.

“Bogus,” he said. “Completely and without any doubt. The lie cannot live forever.”

Many years ago, Golson said he approached a prominent young apostle of the new music. His mind was open and he was eager to understand its value.

“[This man] told me himself it was bogus,” Golson recalled, “though without knowing it. Do you know about bass and treble clefs? The clefs are there only for convenience. You would have too many lines without the clefs. But they have nothing to do with concepts. I asked how he arrived at what he’s doing. He said he played in the ‘tenor clef.’ It was ridiculous. There is no such thing.

“He was a clever man. He took what he didn’t know, and made it into something that seemed unique. He said that he played off the melody, not chords. This was his system, to which he gave a fancy name. What do you think Sam and Cephus said in the cotton fields when they were buck dancing and strumming the banjo? ‘Sam, I think that was a G7 in bar 10?’ Of course not. They played off of the melody. It was intuitive. What do you think professional musicians do today when they don’t know the song a singer is doing in some strange key? They play off the melody. It’s nothing new.

“Then one day I picked up the International Herald Tribune and read a story proclaiming this man a jazz genius who has come up with a new system. He plays off the melody.”

Golson rolled his eyes and slapped the table. “How can people be duped? Free jazz was a way out for a lot of musicians who couldn’t play the changes of ‘All The Things You Are.’ It opened the door to fakery.

“Not that it was invalid,” he added. “There were guys who could play both—like John. That’s why Coltrane was a great musician. He mastered it all. Whether you like where he ended up or not, he’s entitled to our respect.”

Golson presently is completing a book targeted to college and university jazz curriculums, which he hopes to publish later this year. Among the chapters, “The Bogus Genius.”

Golson’s genius is far less controversial. It lives in the easy warmth and fluency of his tenor lines, but his immortality might reside in a catalog of compositions that have taken root as major jazz standards, now with a life of their own.

Although he had recorded about a dozen sessions between 1950 and 1955, it was as a composer that he made his first serious impact when Coltrane brought Golson’s “Stablemates” to Miles Davis in November 1955. The Davis Quintet (and shortly after Coltrane with Paul Chambers) recorded it for Prestige, thus cementing it into the canon of modern jazz titles. Since then, it has been recorded 114 times by Golson and others. Other Golson standards include “Along Came Betty” (78 times), “Killer Joe” (94 times), “Whisper Not” (189 times) and, most famously, “I Remember Clifford,” with 282 recorded versions, according to Tom Lord’s Jazz Discography.

What kind of royalties come from such a songbook? “It varies according to how many plays I get,” he said. “How many recordings, how many performances. BMI keeps track of that. Sometimes it’s close to half a million in royalties. Sometime it’s $200,000. It might not be anything.”

He continues to play those songs today, because he knows his audiences want to hear them. “As much as I play them,” he said, “I try to make something fresh out of them every time. I don’t have any set solo routines. And when I play ‘Clifford,’ it’s a reflective mood for me because I remember all those times we were together. They were the songs that gave me my reputation. I owe them my best, because of what they’ve done for me. No, I don’t mind playing them, any more than I mind signing autographs. It’s a privilege.”

Composing them came with no guarantees, though. “You can’t get up and say, ‘I think I’ll write a hit today,’” he said. “You have to wait and see what the reaction is from the people who pay to see you. When I wrote those tunes, ‘Stablemates’ and ‘I Remember Cifford,’ I had no idea what would happen to them. My wife told me that ‘Killer Joe’ was too monotonous. You never know.

“What gives a composition validity is the knowledge of the person writing it, the experience he can draw on,” Golson continued. “But when you get to the meat of it, it’s in the intervals, what follows what. That’s what a melody is. When I write my songs, I’m conscious of intervals. Art Farmer was conscious of intervals. That’s why he played so beautifully. You get the right intervals in place and you’ve got something that will live past your time—Duke, Coltrane, Bill Evans, Claude Thornhill.”

As a composer, Golson has occasionally served as his own lyricist on songs such as “From Dream To Dream” and “If Time Only Had A Heart”—mainly to deny the opportunity to others. “You have no idea how many sets of lyrics I’ve gotten to ‘Along Came Betty,’” he complained. “I get some every year. Once, a person had the audacity to write a lyric to ‘Whisper Not’ and record it. Legally, I had to get them to take it off the market. I guess they think they’re doing you an honor, when they put words to your songs, and you should be happy about it. But I have to say, ‘I’m sorry.’ I have never approved any of the attempts.”

Not quite never. Leonard Feather added an approved lyric to “Whisper Not,” which Al Jarreau sings on the new Jazztet CD. And Quincy Jones penned the “Killer Joe” lyric. But generally, Golson remains protective of his songs’ integrity. Not even a Jon Hendricks lyric to “Stablemates” made the cut. “I told him, ‘Jon, don’t do that anymore,’” he said. “That’s not the kind of tune for a lyric. Nobody can put a lyric to a tune of mine legally without permission. I usually hate those attempts to take a jazz tune and put a lyric to it. Worse is putting words to improvisations. It’s not my cup of tea.” DB

Tomasz Stańko

(Photo: Andrzej Tyszko)Wasilewski sat between his partners at a conference table in a meeting room in ECM’s Midtown Manhattan offices. Wasilewski and Kurkiewicz were 5 when the shipyard workers of Gdansk began the nationwide strike that would lead to the development of Solidarity, the first independent labor union to exist in the Eastern Bloc. When the Berlin Wall came down, they were 14.

“What happened in Poland in the ’60s did not influence us much,” said Miskiewicz, two years their junior.

“At the same time, our generation had to respect older musicians,” Wasilewski said. “Then in the ’90s, it became a DJ’s world, and it’s now popular to sample and mix music from Polish jazz from the ’60s. This generation realized that the ’60s were important.”

In February 1995, one year after they joined Stańko, before any of them had reached 20, the Simple Acoustic Trio recorded Komeda (Gowi), a mature recital of eight Komeda tracks. Compared to now, Wasilewski’s lines have more notes, the dialogue is more florid and the transitions are less sophisticated, but the group is recognizable. In contrast to the prevailing European ethos of eschewing blues and swing toward the end of constructing an individual tonal identity from local vernaculars, these musicians followed Stanko’s example on Komeda’s Astigmatic, engaging and responding to the building blocks of American post-bop modern jazz—McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, Jarrett — on its own terms.

“It seemed like an obvious thing to do,” Wasilewski said of the repertoire. “We were listening to Komeda’ s quintet recording with Tomasz. He was in the air.”

“It was easy to play, easy to improvise,” Miskiewicz said. “After we made the recording, we started to be more interested in Komeda as a person, what his feelings might have been.”

“He was a window to explore the Polish roots we could be influenced by,” Kurkiewicz said. “But there was a big jazz scene, opposite to the system, and jazz was a synonym of freedom. It was common for jazz to be put into the movies — it wasn’t just Komeda.”

“Komeda wasn’t a virtuoso player, but it doesn’t matter,” Wasilewski said. “Thelonious Monk as well was not so technically great. But at the same time, Monk is one of the most important composers in jazz history. With Komeda it’s the same, but unfortunately he had an accident and died earlier than he should.”

Born in Koszalin, a city on the Baltic Sea, Wasilewski and Kurkiewicz met as 14-year-olds at a music academy in Katowice. “We were focusing on playing jazz, learning jazz every summer with Polish and also American teachers from Berklee College of Music.” At a workshop in 1993, they met Miskiewicz, then 16, and joined forces.

“We want to connect the European and American ways of playing—it doesn’t matter what either one means,” Wasilewski said.

It did seem to matter.

“Rubato tempo playing,” Wasilewski elaborated. “More influence from classical music. More influenced from different folk music — Bulgarian, Romanian, French and Norwegian. Polish, too, though we don’t like it; it’s not so inspiring. Hungarian is more entertaining, stranger, more attractive for us than for Hungarian people. Jazz for me is folk music.”

“We respect the traditional way of playing, and we respect the soul of it,” Miskiewicz said.

“From the beginning we did a lot of jazz and blues form, and it was our best form,” Wasilewski said. “Next we would like to work on developing forms.” He mentioned his admiration for outcats Alexander von Schlippenbach and Peter Brötzmann, with whom Stańko had played in the Globe Unity Orchestra.

“They use not only playing ability,” Kurkiewicz added. “They use the soul, the ghosts, the spirits.”

It seems that always, the whole history of art, people think that if you are old, art is over,” Stańko said. “In our time, everything was more rich, more intense. I try to be like Miles, a little under, a little downstairs, and see what’s really going on.”

Today’s musicians don’t face official censorship, as Stańko did during his youth in Poland. Perhaps the stakes were higher then.

“My generation don’t care about money like these young people now,” the trumpeter said. “But this is not important. The important thing is music. For this reason, I rely on musicians I play with to give me power. Billy Harper give me power. He was fresh in this band, playing free.”

Reflecting on the Komeda compositions that had inspired Harper the night before, Stańko reflected on the Polish cultural streams that inflect his and Komeda’s musical production. “We have a predisposition for anarchy, but also for lyricism, and that is in my music,” he said. “Maybe our weather, the same weather like today, a melancholic mood, a little depression coming from melancholic, but also an ‘agghhh’ coming from drinking too much.”

Drinking perhaps, but then there are the existential realities for Poles who lived first under German and then Soviet occupation. “My father had a quarter Jewish blood,” Stańko said. “In wartime, he was working in the administration of a Polish city. The Resistance was active, and the S.S. was taking people from the streets, and they make a line and every 10th person they shoot. Father had fast reflexes. He spoke German, and he started to speak to the Germans that he work in the city in this administration, and he’s musician. Then they said, ‘Go away.’ I don’t think he thought himself Jewish. I don’t, either, although I am happy that I have this blood. I also don’t feel much Polish. I feel international. I feel human.” DB

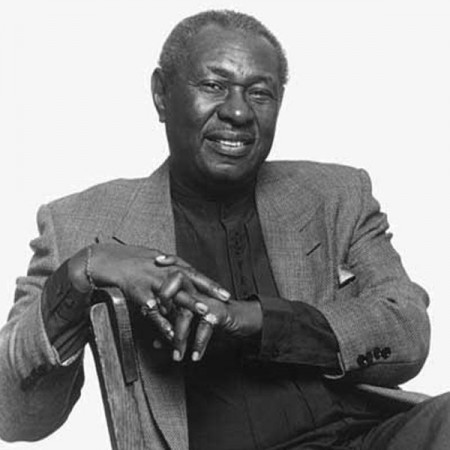

Count Basie (1904–1984)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)Basie: Oh, Lord, that was so. Yeah.

Teagarden: Have you seen Louis lately?

Basie: No, I haven’t seen Pops in a long time.

Teagarden: I miss him by hours sometimes.

Basie: We’re either ahead of him—or behind him, which is the wrong way to be, behind him, you know. But we worked seven, eight days down in the place in Washington together. Boy, that was great. That was the greatest thing I ever did. Man, we just play eight bars of that theme and nothing is going to happen in the next three minutes.

Teagarden: That’s right. Nothing but applause.

DownBeat: Count, why did you keep a big band going, when it became increasingly difficult to keep bands going?

Basie: ’Cause I was simple. There’s nothing else I could do. I can’t play in a small group because you have to play too much. And, then, I guess I’m simple—I just like that sound, that’s all. Excuse me, gentlemen.

[Teagarden and Basie leave to go on stage for finale; 10 minutes later, they return.]

DownBeat: Count, you’ve had a band since the middle ’30s. When you came up within the so-called big-band era, people were dancing, right?

Basie: Absolutely.

DownBeat: Was business good then?

Basie: Well, that was the dance era.

DownBeat: Now, today, there are just a handful of big bands—two of the best being yours and Maynard’s. How does today differ from the ’30s, as far as people dancing? Do people come to hear the band more than they come to dance? Do you play more concerts than you do dances? Just how is it different?

Basie: I think we play more concerts. I know we do, and we get to play a few dances, mostly at the universities, colleges, and things. But as far as our dance career is concerned, it’s been kind of beat. But for the last year or so, it seems as though it’s picking up a bit. That’s mainly due, I guess, to the wonderful work the disc jockeys have been doing on instrumentals throughout the country.

DownBeat: Can you call your band a jazz band and be a dance band at the same time?

Basie: I think you can.

DownBeat: Why?

Basie: I don’t know, but I think you can.

Ferguson: Basie’s band always sounds like a jazz band to me—if I may insert that—and I know what Basie’s doing when he plays an arrangement for dancing and when he chooses certain numbers when he’s on the concert stage. At times, he will play numbers for dancing that he wouldn’t play on the concert stage. But many of them overlap. It’s not like the old saying: “He has two separate books.” I don’t know if anyone ever really had two separate books—I think that was just a phrase.

DownBeat: Maynard, do you play more concerts than dances?

Ferguson: Yes, I would say so, if we are to include jazz clubs as concerts.

DownBeat: When both of you play dances, are some of the kids hard to get on the floor? In other words, Count, do you have to play different now than you did in the ’30s to get people dancing?

Basie: If we’re playing a dance, we find that slower melodies fill the dance floor. It’s still more of a listening audience that we have, especially if we have the teenagers, but if we do have the older people, naturally they’re not going to dance so much, because their dancing has become cut in half, too—unless you play a little slower so they can get together and reminisce a little.

DownBeat: In the ’30s ...

Benny Goodman

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)His general attitude to my queries was one of polite tolerance. He was rather guarded, evincing a sort of quiet, offhanded amusement that I should concern myself with such things. I felt that he considered any discussion of the music business—with me, at any rate—something to be avoided at all costs. But he stated definitely that he considers any discussion of his fellow musicians somewhat unethical. (Come to think of it, I never have heard him really put down anyone behind his back, except in the mildest possible way.) Not all his fellow musicians share this reticence, however.

“In 1935, I was in the front row at the Texas Centennial to hear the band,” Jimmy Giuffre said. “Harry James was in it, Teddy Wilson and Lionel Hampton. I was in high school at the time, and this occasion was one of the most important influences in starting me on my musical career. At that time, I could do nothing but admire Benny’s playing—the great drive and projection, the fluidity, strong technical fluency and feeling. He’s had more influence on more musicians that anyone else that I can think of. Practically all clarinetists have fallen in behind him. They followed his lead, and it was a good lead.

“He’s tried to open up his recent groups to new trends but usually winds up by going back to his old way of doing things. I wrote an arrangement for him once when he had that bop band with Buddy Greco. It was called “Pretty Butterfly,” but he never used it. Why didn’t he use it? Well, if you applied the word ‘why’ to Benny Goodman, you would be in trouble. He throws curves regularly to most people. As an older musician, I think he fears a new era in music that is leaving him behind, so he tries it all for size, and if it doesn’t happen to fit, he discards it and goes back to his old familiar style. What he’s doing now isn’t really interesting to me anymore because it’s the same approach he’s used for 30 years. Now it’s the expected; then it was an innovation. That band he had in 1935 hasn’t ever been topped—Benny really knows how to make a band swing—he had good guys, but it was his know-how that made the thing so great.

“But I can’t really blame Benny for not going any other route; he picks up the horn, and that’s the way he plays. Now, his playing of symphony music—the way it sounds is that instead of playing the music on a personal basis, he tries to be a legitimate clarinet player with a legitimate sound rather than being Benny Goodman. I feel that he assumes the classical player’s role, whereas he should still be himself, because if anyone has an identity, Benny Goodman has. I feel that jazz music has an identity which is difficult to define; it’s a dialect in the player, an accent. I don’t know if Benny is trying to prove something to himself by playing classical music in this legitimate style, but, to me, it just doesn’t come off. I don’t mean that it’s bad playing—he’s just not in his element, not himself.”

Benny’s long-time friend and great admirer, composer Morton Gould, takes a somewhat different viewpoint:

“It’s impossible to be objective about somebody you feel so strongly about. We would be less than human if we were machinelike in our appraisal. I think that Benny is a first-rate artist; I also feel that too often he is just taken for granted. To me, he has the qualities of a truly great artist—consistent musical integrity. He is very demanding of others, and of himself, and though at times he may be seemingly critical of another person, in my close, intimate contact with him, I have never heard him say anything derogatory, mean, or vicious about another person. He is violently super-critical of himself. Perhaps this is why he finds it so hard to find the right people to work with him.

“Benny, with all his worldwide success and acclaim, is actually a very shy person. He wants to be left alone. Basically, he’s a simple man, with no ostentation—very honest. He has none of the superficial ornamentation that sometimes goes with the public image of a famous personality. He always has his feet on the ground. The legend is that he is unapproachable. Well, basically, he is an introspective person, and, to me, it’s symbolic that a man who has lived though and been a part of so much jazz history as he has could have come away unscathed by the more lurid aspects of the business.

“To sum up my feelings about Benny the man, I feel that he is a very warm and compassionate human being, and I have a tremendous admiration for him. There still is a kind of vitality, virtuosity and imagination in his music. Maybe he’s not in vogue just now with the young set, but, nevertheless, his facility and command of the instrument are just as great as they ever were. All you have to do is listen to other clarinetists—and I mean beyond jazz—I mean that as a clarinetist, not as a jazz artist, he is a fabulous performer. I’ve heard him play and do things on the highest level of musical art.

“Why should a man like Benny Goodman be expected to become far out or be whatever is currently fashionable? All these developments in music are exciting. Popular music, by its very nature, has to change, but somehow one doesn’t expect an Elman or a Heifetz to change his style. I think it’s a little unfair to expect one generation to continually remake itself in the image of the generation that comes after it. It’s not in the cards.”

Pianist John Bunch, who was with Benny on the 1962 State Department tour of Russia and who also was in the group with which I played, seems to have insight into some of Benny’s other aspects. “Benny always seems happier with a small group, but really he’s the most complicated person I’ve ever met, as far as trying to explain him to anyone, or to myself,” John said. “I’m sort of proud that I’ve been able to get along with him so well, personally and musically. I have played seven tours with him. The first one was in 1957, and the more I think about it … wow! … the more I wonder how I’ve managed to stay on such good terms with him.

Lena Horne

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)After Lena had said goodbye to Daddy, while we proceeded downtown with her personal manager, Ralph Harris, the conversation took a more general turn. “Is the album with Duke and Ella out yet? That ought to be too much—what a marriage!” And, after we had all cast critical eyes on an Edsel that had passed, “We still have the same Jaguar we bought in Coventry, England, in 1950, and we’re still happy with it.” And, “When is Basie opening at Birdland—Thursday? Well, you know we’re going to be there!”

As the traffic slowed us almost to a standstill downtown, Lena’s fierce, darting eyes found stimulation in every passing stranger, every unexpected sight. … “Look at the guy standing on the corner there. You know he’s got to be Italian—the high shirt and those shoes. And you know, he’s very pretty!” A little later, as a bent, elderly man shuffled by, pushing a heavy hair dryer along the street, her face was suddenly downcast. “Look at that poor old man—isn’t that sad?” And when two orthodox Hebraic types with the traditional black hats and ear locks walked by: “Did you see those men? … Ooh, I just love New York!”

Just before we reached her destination, I asked Lena whether she felt her style had changed perceptibly. “Well, people are always saying, ‘Oh, you’ve changed your style,’ but I’d get bored to death if I thought I was a lot like I used to be five years ago. I still want to make sure that what I’m doing is what I want.”

“Now that you’ve settled down in Jamaica and have enough confidence in yourself as an actress,” I said, “do you think you might ever take a strictly dramatic part that didn’t call for any singing at all?”

“Not soon, I think. After all, people still know me essentially as a singer. But you know how I am—I didn’t think I was even capable of doing this job, and I always have to have Lennie hit me over the head about 12 times and say, ‘You can do it—go ahead and do it!’”

Lena got out of the cab, turned the uniquely vivacious freckled face and said goodbye. As her slender figure disappeared into the jewelry shop, she recalled a line from her autobiography. “I feel that my glamour days are rapidly disappearing,” she had said. The book was published in 1950. Today Lena has a graceful and beautiful grown-up daughter; a handsome son; a man in her life at once husband and “Daddy” and gentlest of teachers; and a place she can call home for her family in her native town.

If her glamour days are disappearing, there must be something disturbingly wrong with the vision of the audiences who pack the Imperial theater every night, for whatever the formula—perhaps a blend of maturity, security and the natural beauty that was hers all along—Lena Horne at 40 is the most glamorous sight in the city she has chosen to call home. DB

Tony Williams

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)DB: Were you thrilled to be part of the Miles band in the ’60s?

TW: Well, when you’re doing things it’s hard to say, “Oh gee, this is going to be real historical sometime.” I mean you don’t do that; you just go to the sessions, and 10 or 20 years later people are telling you that it was important. When you’re doing it, you can’t really feel that way.

DB: What is your relationship with Miles now?

TM: Very friendly. I saw him this summer. I haven’t heard the new albums, but when we played opposite him, I heard bits and pieces of the band, and Miles was sounding good. He’s been practicing. I liked Al Foster [Miles’ drummer] years ago, when I was with Miles.

DB: You’ve played with a lot of illustrious musicians. Being a drummer, you have to adapt to each one differently. Let’s talk about some of them, say, beginning with Sonny Rollins and McCoy Tyner.

TW: Sonny has a very loose attitude about things—the time, the whole situation. With McCoy I always felt like I was getting in his way, or that it never jelled. I felt inadequate. Actually, with both Sonny and McCoy, it’s like you’re playing this thing, and they’re going to be on top of it.

DB: How about John McLaughlin and Alan Holdsworth?

TW: Completely different. John is more rhythm oriented. He plays right with you, on the beat. He’ll play accents with you. Even while he’s soloing, he’ll drop back and play things that are in the rhythm. Alan is less help. With Alan it’s like he’s standing somewhere and he’s just playing, no matter what the rhythm is.

DB: Wynton Marsalis and Freddie Hubbard?

TW: Freddie plays the same kind of solo all the time. I get the feeling that if Freddie doesn’t get to a climax in his solos, and people really hear it, he gets disappointed. With Wynton it’s always different. I don’t know what he’s going to play. It’s always stimulating.

DB: I gather you think Wynton Marsalis’ manifesto about only playing jazz—and not funk or rock—is not that important?

TW: He thinks it’s an important attitude. That’s what counts.

DB: A lot of fans and critics still find a contradiction in your playing what they see as oversimplified rock as well as the kind of complex jazz you played with Miles and you play now with VSOP. What’s your reaction to that?

TW: Well, first of all, just because it’s jazz, doesn’t mean it’s going to be more complex. I’ve played with different people in jazz where it was just what you’d call very sweet music. No type of music, just because it’s a certain type of music, is all good. A lot of rock ’n’ roll is not happening. And a lot of so-called jazz and the people who play it are not happening. Complexity is not the attraction for me, anyway—it’s the feeling of the music, the feeling generated on the bandstand. So playing in a heavy rock situation can be as satisfying as anything else. If I’m playing just a backbeat with an electric bass and a guitar when it comes together, it’s really a great feeling.

DB: You were quoted in [an article in] Rolling Stone, praising the drummer in the Ramones. Were you serious?

TW: I don’t remember the occasion, but I do like that kind of drumming, like Keith Moon, any drumming where you have to hit the drum hard; that’s why I like rock ’n’ roll drumming.

DB: Sometimes so much of that music seems very insensitive.

TW: It depends on what you’re saying the Ramones are supposed to be sensitive to. Just because it’s jazz doesn’t mean it’s going to be sensitive. You’re trying to evoke a whole other type of feeling with the Ramones. When I drive through different cities and I look up in the Airport Hilton and I see the sign that says, “Tonight in the lounge, ‘live jazz’”—I mean, what the hell does that even mean? I’m not saying everybody’s like this, but I can see a tinge of people saying, “This is the only way it was in 1950, and we’re going to keep it that way, whether the music is vital or not, whether or not what we end up playing sounds filed with cobwebs.” When John Coltrane was alive, there were all kinds of people who put him down. But these same people will now raise his name as some sort of banner to wave in people’s faces to say, “How come you’re not like this?” These same people. That’s hypocrisy, and I find it very tedious.

DB: How important is technique?

TW: You’ve got to learn to play the instrument before you can have your own style. You have to practice. The rudiments are very important. Before I left home, I tried to play exactly like Max Roach, exactly like Art Blakey, exactly like Philly Joe Jones, and exactly like Roy Haynes. That’s the way to learn the instrument. A lot of people don’t do that. There are guys who have a drum set for two years and say they’ve got their own “style.”

DB: How can we prevent those kinds of guys from taking up more room than they deserve?

TW: [laughing] Well, we could pass a law.

Dexter Gordon (1923–1990)

(Photo: Rob Bogaerts/National Archives of the Netherlands)

Claudio Roditi (1946–2020)

(Photo: David Gahr)

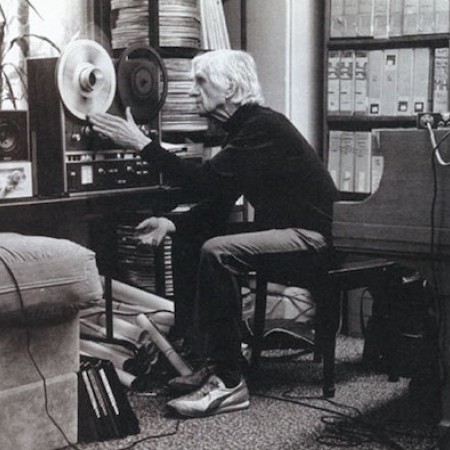

Gil Evans (1912–1988)

(Photo: Carol Friedman/gilevans.com)Gil led his own band in Stockton, California, from 1933 to 1938, playing accompaniment-rhythm piano and scoring a book of pop songs and some jazz tunes. When the band was taken over by Skinnay Ennis, Gil remained as arranger until 1941.

“I was also beginning to get an introduction to show music and the entertainment end of the business,” Evans recalls. “We used to play for acts on Sunday nights at Victor Hugo’s in Beverly Hills, and the chance to write for vaudeville routines gave me another look at the whole picture.”

Thornhill had also joined the Ennis arranging staff, and the two wrote for the Bob Hope radio show while the Ennis band was on the series. The radio assignments gave Evans more pragmatic experience in yet another medium.

“Even then,” Evans remembers, “Claude had a unique way with a dance band. He’d use the trombones, for example, with the woodwinds in a way that gave them a horn sound.”

In 1939, Claude decided to form his own band. Evans recommended the band for a summer job at Balboa, and he notes that Claude was then developing his sound, a sound based on the horns playing without vibrato except for specific places where Thornhill would indicate vibrato was to be used for expressive purposes.

“I think,” Gil adds, “he was the first among the pop or jazz bands to evolve that sound. Someone once said, by the way, that Claude was the only man who could play the piano without vibrato.

“Claude’s band,” continues Evans, “was always very popular with players. The Benny Goodman band style was beginning to pall and had gotten to be commercial. I haunted Claude until he hired me as an arranger in 1941. I enjoyed it all, as did the men.

“The sound of the band didn’t necessarily restrict the soloists,” Gil points out. “Most of his soloists had an individual style. The sound of the band may have calmed down the over-all mood, but that made everyone feel very relaxed.”

Evans went on to examine the Thornhill sound more specifically: “Even before Claude added French horns, the band began to sound like a French horn band. The trombones and trumpets began to take on that character, began to play in derby hats without a vibrato.

“Claude added the French horns in 1941. He had written an obbligato for them to a [Irving] Fazola solo to surprise Fats. Fazola got up to play; Claude signaled the French horns at the other end of the room to come up to the bandstand; and that was the first time Fazola knew they were to be added to the band.

“Claude was the first leader to use French horns as a functioning part of a dance band. That distant, haunting, no-vibrato sound came to be blended with the reed and brass sections in various combinations.

“When I first heard the Thornhill band,” Gil continued, “it sounded, with regard to the registers in which the sections played, a little like Glenn Miller, but it soon became evident that Claude’s use of no vibrato demanded that the registers be lowered. Actually, the natural range of the French horn helped cause the lowering of the registers. In addition, I was constantly experimenting with varying combinations and intensities of instruments that were in the same register.

Thelonious Monk (1917-1982)

(Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Library Of Congress)Piano Focal Point

“If my own work had more importance than any others, it’s because the piano is the key instrument in music,” he continued. “I think all styles are built around piano developments. The piano lays the chord foundation and the rhythm foundation, too. Along with bass and piano, I was always at the spot, and could keep working on the music. The rest, like Diz and Charlie, came in only from time to time, at first.”

By the time we’d gotten that far, we had arrived at Minton’s, where Thelonious headed right for the piano. Roy Eldridge, Howard McGhee and Hill dropped around. McGhee, fascinated, got Thelonious to dream up some trumpet passages and then conned Thelonious into writing them down on some score sheets that happened to be in the club.

Hill Gives Credit

Hill began to talk. Looking at Thelonious, he said: “There, my good man, is the guy who deserves the most credit for starting bebop. Though he won’t admit it, I think he feels he got a bum break in not getting some of the glory that went to others. Rather than go out now and have people think he’s just an imitator, Thelonious is thinking up new things. I believe he hopes one day to come out with something as far ahead of bop as bop is ahead of the music that went before it.

“He’s so absorbed in his task, he’s become almost mysterious. Maybe he’s on the way to meet you. An idea comes to him. He begins to work on it. Mop! Two days go by and he’s still at it. He’s forgotten all about you and everything else but that idea.”

While he was at it, Teddy told me about Diz, who worked in his band following Eldridge. Right off, Gillespie showed up at rehearsal and began to play in an overcoat, hat and gloves. For a while, everyone was set against this wild maniac. Teddy nicknamed him Dizzy.

Dizzy Like a Fox

“But he was Dizzy like a fox. When I took my band to Europe, some of the guys threatened not to go if the frantic one went, too. But it developed that youthful Dizzy, with all his eccentricities and practical jokes, was the most stable man of the group. He had unusually clean habits and was able to save so much money that he encouraged the others to borrow from him, so that he’d have an income in case things got rough back in the states!” DB

Lennie Tristano (1919-1978)

(Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Library Of Congress)

Joni Mitchell performs in 1983.

(Photo: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic)Anyway, by my doing this card, he introduced me to some jazz. Then I heard, at a party, Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, The Hottest New Sound In Jazz, which at that time was out of issue up in that part of the country, in Canada. So, I literally saved up and bought it at a bootleg price, and in a way, I’ve always considered that album to be my Beatles, because I learned every song off it. “Cloudburst” I couldn’t sing, because of some of the very fast scatting on it; but I still to this day know every song on that album. I don’t think there’s another album that I know every song on, including my own.

I loved that album, the spirit of it. And like I say, it came at a time when rock ’n’ roll was winding down, just before the Beatles came along and revitalized it. And during that ebb, that’s when folk music came into its full power.

What were the Miles Davis albums?

Sketches Of Spain. I must admit that it was much later that Miles really grabbed my attention ... and Nefertiti and In A Silent Way became my all-time favorite records in just any field of music. They were my private music; that was what I loved to put on and listen to—for many years now. Somehow or other, I kept that quite separate from my own music. I never thought of making that kind of music. I only thought of it as something sacred and unattainable. So, this year was very exciting to play with the players that I did.

You did let your hair down one time when you did “Twisted.”

Right—and “Centerpiece,” I also did that. One by one, I’ve been unearthing the songs from that Lambert, Hendricks & Ross album.

But there’s no seeming relationship between the two worlds ...

Which two worlds are you referring to?

The world of music you recorded and the jazzworld.

All the time that I’ve been a musician, I’ve always been a bit of an oddball. When I was considered a folk musician, people would always tell me that I was playing the wrong chords, traditionally speaking. When I fell into a circle of rock ’n’ roll musicians and began to look for a band, they told me I’d better get jazz musicians to play with me, because my rhythmic sense and my harmonic sense were more expansive. The voicings were broader; the songs were deceptively simple. And when a drummer wouldn’t notice where the feel changed or where the accent on the beat would change, and they would just march through it in the rock ’n’ roll tradition, I would be very disappointed and say, “Didn’t you notice there was a pressure point here” or “Here we change,” and they just would tell me, “Joni, you better start playing with jazz musicians.”

Then, when I began to play with studio jazz musicians, whose hearts were in jazz but who could play anything, they began to tell me that I wasn’t playing the root of the chord. So, all the way along, no matter who I played with, I seemed to be a bit of an oddball. I feel more natural in the company that I’m keeping now, because we talk more metaphorically about music. There’s less talk and more play.

You’ve been associating with jazz studio musicians for how long?

Four years. I made Court And Spark five albums ago.

Did that come about by design or by accident?

The songs were written and I was still looking for a band intact, rather than having to piece a band together myself. Prior to that album, I had done a few things with Tom Scott, mostly doubling of existing guitar lines. I wanted it to be a repetition or gilding of existing notes within my structure. So, through him, I was introduced to that band. I went down to hear them at the Baked Potato in Studio City and that’s how all that came about.

They all found it extremely difficult at first, hearing the music just played and sung by one person; it sounded very frail and delicate, and there were some very eggshelly early sessions where they were afraid they would squash it, whereas I had all the confidence in the world that if they played strongly, I would play more strongly.

So, from that point on, you worked with the L.A. Express?

We worked together for a couple of years, in the studio and on the road.

Trumpeter Lee Morgan (1938–’72) performs with the Jazz Messengers on Nov. 15, 1959, at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam.

“If a guy comes into a record company and says, ‘Look, give me $1,000 for publicity for the Fifth Dimension’—it could be any of those rock groups—solid. You come in and ask for $200 to pay for two 30-second spots to advertise a jazz record, and they look at you like you’re crazy. They just don’t want to spend any money.

“It’s almost like a conspiracy. It would help them to advertise. Everybody could make money from the music, but everybody is happy to keep the level of AM daytime listening in a trash bag.”

The U.S. Information Agency makes propaganda specials, Morgan said, pointing out that last spring there was one featuring Nipsey Russell with Billy Eckstine, Joe Carroll, Etta Jones “and a guy from the Metropolitan Opera.” Morgan was on it, too, with a big band. “It’ll be shown all over the world to foster good relations with our government,” he said, but added, ruefully, “probably nobody here will ever see it.”

“Even superstars like Miles Davis and Duke Ellington don’t get the exposure of Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic,” he said. “Maybe this music of ours isn’t meant for the masses. But he’s held as a great conductor, and he lives in a penthouse, and he’s rich, and he conducts the New York Philharmonic in Lincoln Center. And Coltrane had to be playing in Slugs’. That’s the difference.

“See, Leonard Bernstein plays to a minority audience, too, because everybody can’t like symphony orchestras. But symphony orchestras are subsidized. And jazz should be subsidized. This is the only thing from America. The United States ain’t got nothing else but what we gave it, man. And that seems to be the reason it gets the short end of the stick of everything.”

Though angry about the mass media, Morgan is happy about the young people of today.

“Thanks to them,” he said, “music has gotten much better. And when I was a kid, white people had one way of dancing and we had another. Now, everybody dances the same. Rock and jazz—it’s all good music. Now, you go over to Europe, and you might be on a concert or a TV show opposite The Doors, and it would be very successful. The ones in charge in the United States don’t want to do this. Like I said before, jazz is still a thing that’s dominated by Blacks. At first, there was blues and rhythm-and-blues, and then the white man got a hold of it, and it was rock. Rock didn’t start in Liverpool with the Beatles. All that long hair and stuff came later. But most of the whites got the most money from it.”

Noting that the work of some successful rock groups has an intricacy comparable to jazz, Morgan observed that even with its new hipness, rock “is selling millions. So, I don’t want to hear that stuff about they can’t sell jazz, because the music’s gotten so now that rock guys are playing sitars and using hip forms, and Miles is using electric pianos. Music’s gotten close. There are no natural barriers. It’s all music. It’s either hip or it ain’t.” DB

Art Tatum (1909–’56)

(Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Library Of Congress)

Lee Konitz (1927–2020)

(Photo: Jimmy Katz)“I enjoy making the singing feeling dictate the playing feeling, not the finger technique, which I tried to develop for many years, like most people,” Konitz said. “I’m a shy person to some extent, and I never had confidence to just yodel, as I refer to my scat singing. One day with Dan, I played a phrase and needed to clear my throat, so I finished the phrase, bi-doin-deedin-doden, or whatever, and then a few bars later Dan did something like that. So, I said, ‘Oh, good—I’m in now; I can do this.’ I don’t get up to the microphone. I don’t gesticulate. I just sit in a chair, and whenever I feel like it, at the beginning of a solo or in the middle or whenever, I warble a few syllables. I’ve been warbling ever since, and feel great about the whole process.”

As a teenager in Chicago, Konitz—then an acolyte of Swing Era altoists Johnny Hodges and Benny Carter—played lead alto and sang the blues at the South Side’s Pershing Ballroom in a black orchestra led by Harold Fox, the tailor for Jimmie Lunceford and Earl “Fatha” Hines. Seventy years later, he scatted with Douglas in England and with Bro in Scandinavia. Just three months earlier, he scatted several complete solos on the sessions that generated the new recording with Denson, following three albums on Enja with the collective trio Minsarah: Standards Live– At The Village Vanguard (2014), Lee Konitz New Quartet: Live At The Village Vanguard (2009) and Deep Lee (2007). Denson recalled that when he and his Minsarah partners, pianist Florian Weber and drummer Ziv Ravitz, first visited Konitz in Cologne, he immediately suggested they sing together.

“After several minutes, Lee said, ‘Sounds like a band,’” Denson recalled. “For years traveling on the bus, we’d sing and trade and improvise, but never on stage until last October, when we were touring California. We went to extended phrases, then to collective improvising. We decided to record it, so I booked a show at Yoshi’s in February, and went into the studio.

“His vocal solos are beautiful. Lee told me that over the years he’s worked to edit his playing to pure melody. If you listen to the young Lee, it’s virtuoso, total genius solos. Now, it’s still genius but a very different mode—all about finding these beautiful melodies. That sense of melody continues to capture me. So does Lee’s risk-taking, his desire not to plan some ‘hip’ line that he knows will work, but to take something from his surroundings, so that the music is pure and truly improvised in the moment.”

On June 9, 2011, during soundcheck for a concert with Tepfer’s trio and guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel in Melbourne, Australia, Konitz suffered a subdural hematoma and was hospitalized for several weeks. “He made an unbelievably miraculous recovery, and when we started playing again something had changed,” said Tepfer, whose recorded encounters with Konitz include Duos With Lee (Sunnyside) and First Meeting: Live In London, Volume 1 (Whirlwind), a four-way meeting in 2010 with bassist Michael Janisch and drummer Jeff Williams. “When I first played with him, Lee was open to pretty out-there experimentation. I realized he was no longer interested in anything that resembled noise. He was very interested in harmony and playing together harmoniously. That’s a real shift in his priorities, and it took me a while to get used to it. But we’ve done a lot of touring in the last six months, and the playing together feels powerful. We’re playing standards and some of Lee’s lines, which are based on standard chord changes. Lee is entirely comfortable with any harmonic substitution or orchestration idea as long as it’s clear and musical and heartfelt. There is tremendous freedom in that restricting of parameters.”

On the phone from Aarhus, Denmark, after the second concert of his tour, Bro described the effect of Konitz’s instrumental voice. “I’ve listened to all his different eras, and it seems the things he’s describing with his sound are becoming stronger and stronger,” he said. “When he plays a line, a phrase, it sounds clearer than ever. It has a lot of weight. I don’t know any young players that have it. Lee moves me so much. He plays one note, and I’m like, ‘How the hell did he do that?’ The sounds become more than music, in a way.”

Douglas recalled a moment in England when Konitz played “Lover Man,” which he famously recorded with Stan Kenton in 1954. “It was a completely new conception, of course with a kinship to that great recording,” Douglas said. “But what struck me most is how much his melodic invention is wrapped up in his warm, malleable tone that at times seems unhinged from notions of intonation or any sort of school sense of what music is supposed to be. It has a liquid quality, like the notes are dripping off the staff. Everyone was stunned that he pulled this out in the middle of the set.”

What these younger musical partners describe is the antithesis of “cool jazz.” That’s a term that critics attached to Konitz for the absence of what he calls “schmaltz” and “emoting on the sleeve” in his improvisations with Tristano, the Birth Of The Cool sessions, Gerry Mulligan’s combos, and during his two years with Kenton, when he emerged as the only alto saxophonist of his generation to develop a tonal personality that fully addressed the innovations of Charlie Parker without mimicking his style.

“To me, Lee combines Lennie’s rigorous, almost intellectual manufacturing of the line, with a huge heart and a desire to communicate,” Tepfer said. “I clearly remember that what first struck me when I met him is that there was never any misunderstanding. If Lee doesn’t understand you, he’ll always ask you to repeat it. He often says, if you say something on the money, ‘You ain’t just beatin’ your gums up and down.’ What he stands for in music is very much that. I think there’s nothing worse to Lee than people saying things just to say things, or playing things just to play some notes. There always has to be meaning, and intent to communicate that meaning to other people. What I described about his current passion for playing harmonious music, playing together with no semblance of noise or discordance, I think comes from an even more intense desire to communicate as he’s getting older.

“There has to be a question of what improvisation is and why we would do it, and whether it’s a meaningful thing or not. I think of all the people in the world, Lee stands as a beacon of truth in improvisation. There aren’t many like him, where you listen and come away with, ‘OK, that’s why we do this.’”

Konitz allowed that playing with Tepfer, Brad Mehldau or with Frisell, “or whomever I’m playing with who’s really listening and pushing a little bit in some positive way,” makes him “less inhibited to open up.”

He was asked about overcoming that shyness when he came to New York in 1948, at 21, and plunged into direct engagement with the movers and shakers of late-20th century jazz vocabulary. “Lennie’s encouragement had a lot to do with the playing ability that I became more confident in,” Konitz said. “I was always so self-critical; it was sometimes pretty difficult. But I was sometimes able to play. Marijuana had something to do with it, I confess. But at a certain point, I stopped it completely. I appreciated that, because whatever I played, it was more meaningful to me, and I felt totally responsible for it.”

Sixty-seven years after arriving in New York, Konitz is finally a member of the DownBeat Hall of Fame. “It’s the ‘ain’t over until it’s over’ syndrome, and I deeply appreciate it,” he said. “I appreciate being around to say thank you. It’s romantic and poetic, and I’m accepting it on that level, and for being honored for trying to play through the years.”

Konitz keeps moving. He’s focused on his itinerary immediately after he turns 88 on Oct. 13. “I’ve got a lineup of tours coming up, all over the U.S. the last part of October; all over Europe, day by day, in November,” he said. “I’m pleased that I can do it.” DB

Sarah Vaughan (1924–1990)

(Photo: Nationaal Archief, The Hague)Treadwell decided something must be done to give her confidence. He invested all the money he had, about $8,000, in the building of a star. He arranged for nose-thinning plastic surgery on her face and the straightening of her teeth and sent her to a beauty salon to have her figure streamlined. He paid for special arrangements and elocution lessons, and personally selected and bought becoming clothes for her.

It worked. So transformed and elated was she that he gave her a nickname. That’s how she came be known as “Sassy.”

Yet, Vaughan today doesn’t like to talk about her first marriage. “I want to forget that,” she said. “I never want to think about that again.”

Asked directly whether she thinks Treadwell should be given credit for guiding her to stardom, she revealed her tendency to rely on things current.

“No, my second husband did that,” she said.

“All George ever did for me,” she maintained, “was really for himself. You know, nobody wants to print that, but it’s the truth, and I wish people would understand that.”

Vaughan’s second husband is C.B. Atkins, a Chicago businessman and taxicab company owner whom she married in the summer of 1958 after a whirlwind courtship.