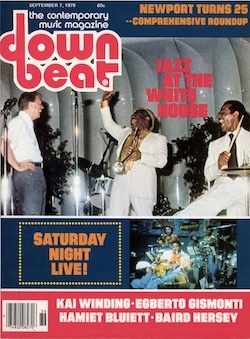

The cover image of DownBeat’s Sept. 7, 1978, issue, which featured in-depth coverage of President Jimmy Carter’s jazz picnic party on the White House’s South Lawn. The historic gathering honored and was honored by a history of jazz that embraced everything from ragtime through the avant garde.

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)

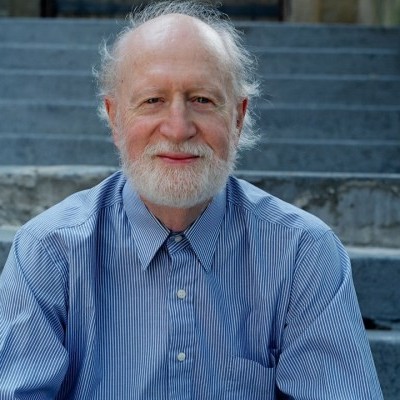

“If you never suffered, you can’t play the blues,” says Lou Donaldson.

(Photo: Tomas Ovalle)

The candidate and his crew, from left, Kenny Barron, James Moody, Rudy Collins, Dizzy Gillespie, Chris White and Shelly Manne.

(Photo: Robert Skeetz)

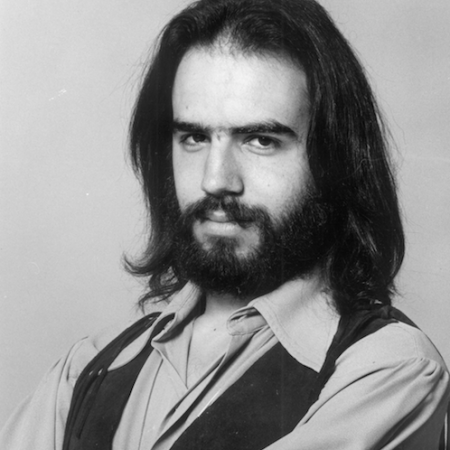

Albert Ayler

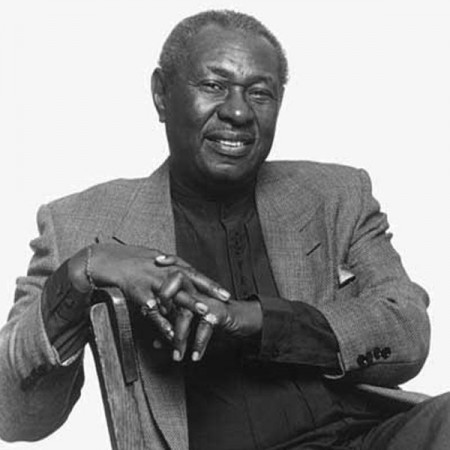

T.S. Monk at home

(Photo: Michael Weintrob)For jazz musicians, the first line of communication is to the other musicians with you on the bandstand. And there’s a respect that goes along with that. If everybody played it right and you know you played it wrong, don’t act like you didn’t play it wrong. Sound everybody [out], and say, “You know, I jammed that up. And thank you, you gave me that ‘one’ that got me back. And thank you for not freaking out because I know the changes were jammed up.”

THELONIOUS USED TO TEACH lessons like that all the time. He taught Ben Riley a lesson in lateness once. This was before I was playing with the band. They were playing in Cleveland. I’ll never forget because it was a gangster joint called Leo’s Casino. And when we got in the joint, I swear everybody in the joint looked like they were straight out of The Godfather.

Across the street from Leo’s Casino was a strip joint, right? The two young guys in the band were Larry Gales and Ben Riley. So, naturally, in between sets these guys are saying, “Hey, let’s go see what the girls are doing.” So they started going over to see what the girls were doing. They were going over every night … . But I could see, because I was going to the club every night, that they were cutting it closer and closer and closer to set time. And this one night, Larry Gales came running back, but Ben ain’t there. And Thelonious was of a mind [T.S. looks at his watch]: “Hit it.” So, they hit without Ben Riley. This is going to sound unbelievable, but I swear I’m not lying. About 10 minutes into the set, Ben Riley comes running into the club … running into the club. He done jammed up. He runs up onto the bandstand and gets into the groove. So, I’m sitting there saying, “OK, everything’s groovy now. Everything’s cool.” So, Rouse takes a solo, Thelonious takes a solo and Larry Gales takes a solo. And Ben goes to take his solo.

When Ben takes his solo, Thelonious gets up off the piano. He looks at Rouse and says, “Come here.” He looks at Larry Gales and says, “Come here.” They go walking down off the bandstand, and he looks at me and says, “C’mon.” I follow him. We go out of the club. We get in a taxi. We go back to the hotel. We go up to the room. Thelonious had a room with a record player. He puts on Art Tatum. So, me, Thelonious, Charlie Rouse and Larry Gales are back at the hotel listening to Art Tatum records.

Nobody’s saying a word. Larry and Rouse ain’t saying nothing to Thelonious. I don’t know what’s going on, so I’m not saying anything. I’m just following everybody. I swear we must have stayed there for 15 or 20 minutes. All of a sudden, Thelonious says, “OK, let’s go back.”

We go downstairs. We have to wait for the guy to get us a cab. We get a cab. We go back to the club. I can tell you that when we got back to the club, Ben Riley was a shell of his former self. He had been up on that bandstand for about 45 minutes soloing. Needless to say, Ben Riley was never late again. [laughs]

WHAT HAPPENED TO JAZZ EDUCATION in the first 40 years was that it was discovered. It was realized that this music, which came from these untrained, sometimes uneducated African Americans, was one of the most highly intellectual endeavors ever tried on the planet Earth. And when white music educators discovered that, they tried to hijack the music without the artisans. So, for instance, by the mid-’60s, schools were creating curricula on bebop. Now, in the 1960s, Thelonious Monk was alive. Dizzy Gillespie was alive. Max Roach was alive. Hank Jones was alive. Roy Haynes was alive. All those founders of bebop were alive. Did any of them get a call from a curriculum development person? No, they didn’t.

THE THELONIOUS MONK INSTITUTE OF JAZZ was formed in 1986. Basically, the idea was to recreate the interface that I had grown up with. I knew the best way to teach jazz was to put young musicians with the masters. That’s how I learned. That’s how my daddy learned. That’s how John Coltrane learned. That’s how Miles learned. That’s how everybody learned. So, this is very different than how you teach European classical music.

Jazz is a very hands-on music. It’s passed down personally. It comes out of the African tradition—the oral tradition. So, you pass it down that way. And that is what gave rise to the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz. In the past 25 years, we have tried to interact with anybody who is anybody in jazz. And, more importantly, we’ve tried to interact with everybody who has been profoundly influenced by jazz.

EVERY PROGRAM for the past 25 years, every single program that the Monk Institute has done, has been 100 percent free for our students. No kid has had to pay a nickel to interact with Herbie Hancock; not a dime to interact with Ron Carter or Wayne Shorter or Jimmy Heath or Clark Terry or any of the people who have been involved.

THIS IS THE MOST wonderful music. This is the most human music of all time. It will never go anywhere unless human beings stop desiring to be individuals. And that’s not going to happen. So, we are healthier now, despite marketplaces and all that stuff. As an art form, we are healthier now than we have ever been. DB

At 25 years old, bassist Esperanza Spalding wasn’t overly concerned with marketability.

(Photo: Sandrine Lee/Montuno Productions)

In addition to making significant contributions to the jazz canon’s batch of standards, saxophonist Benny Golson appeared in a pair of films and was photographed in “A Great Day In Harlem.”

(Photo: Oliver Rossberg)

Tomasz Stańko

(Photo: Andrzej Tyszko)

Count Basie (1904–1984)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)Basie: They were doing the Lindy Hop in those days. Sometimes you couldn’t play too fast. That’s when they were really doing the Lindy.

Ferguson: Basie, did you see that again in Sweden?

Basie: Yes, yes, I did.

Ferguson: You know, when we played the dances in Sweden—the first night I played nothing above a medium tempo, and I thought, “Gee, they dance to that awful easy.” And then I started getting into these faster things that really are the things we play in the jazz clubs. They are melody dancers in Sweden. If you play well-known jazz standards, and you play them fast, they’ll just start walking around the floor, and they all do it like puppets—they all do it together.

DownBeat: What do you mean melody dancers?

Ferguson: They love American jazz standards. By that I mean, I would have been a smash hit if I would have had “Honeysuckle Rose” in the book. I was speaking about the commercial dance public, for which you could play very hip music.

DownBeat: The average age of your band, Maynard, is about 26?

Ferguson: Right.

DownBeat: And, Count, the average age of your band is ...

Basie: Don’t say it!

DownBeat: But what can be said about the youth of Maynard’s band as opposed to the polish and massive musicianship of your own band—men who have played longer?

Basie: You just said it. They just played longer, not that they played any better, they just played longer. ... Let me tell you something—we haven’t been old all these years. Like the teenagers now—well, we were playing to their parents, and they were young then. I mean, like we haven’t always been 90 years old. Twenty years ago, remember, I was 20 years younger, too.

DownBeat: If you and Basie have to play more concerts and dances than you do jazz clubs, do you think this compromises you as jazz musicians leading big jazz bands?

Ferguson: One of the greatest things to do is to try and always find out how you can be happy in what you do, and one of the things I spend a lot of time on is seeing how I can play jazz at a dance. And I think that in Jack Teagarden’s day he did a great job—days when you could have just played the melody and they could have danced. Instead, you figured, “I’ll start off with the melody, then I’ll go from there and do my own scene.”

Teagarden: Start my melody first. I’ve given this a lot of thought, because I’ve lived through this whole generation. I’m almost 58. I think if the television and radios would have more programs like [International Hour: American Jazz]. ... For instance, this will be talked about for several weeks—like when they had the Timex programs, the great shows that they had about once every six months—there was a lot of comment, but there was nothing solid. The have to keep it up, have some live music on television, and it’ll make people come back to listen to music again—they just don’t get to hear enough music.

Then, I think a lot of the fault of where the dancing went was the musicians themselves. Now, I’m not criticizing us. We’re all a little bit of a ham in a way, which I guess is true in any business. But you just can’t go out there and play every number fast to show off your technique. You’ve got to play some numbers for the dancers.…Dancing is a romantic recreation. Play four tunes for the public and one for yourself; “Stardust” and a lot of pretty things ... it’s real beautiful for romantic dancing—and then let them all ride.

Basie: You sneak one in.

Teagarden: You sneak one in.

Ferguson: Jack, one thing I’ve always felt, when you play at a university ... when Count Basie or Maynard Ferguson play for a prom, where we won’t have as many esthetic kicks, shall we say; nonetheless, the whole student body comes to that dance. And I’m sure Basie puts on a jazz concert for them in the middle of the evening—just as I do. And what happens is that you gain a lot more new fans for jazz in general, as well as for yourself at the dance than you do at the concert.

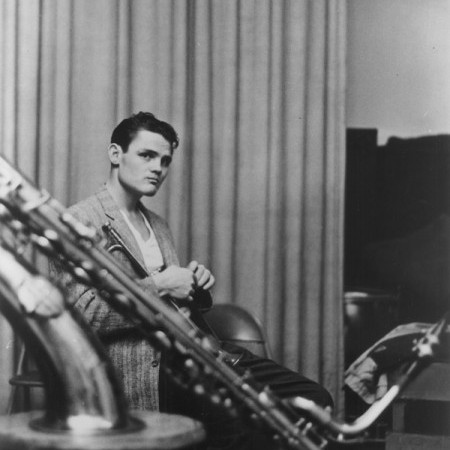

Benny Goodman

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)“When we were on that Russian thing, Benny played some of my arrangements, and I wrote a couple of tunes which he played and recorded. … A lot of people who haven’t had any experience of how he acts get pretty shook up, but I was not so disappointed—hell, I expected it! Knowing him, I know it doesn’t take much to set him off, and he really was under a lot of pressure in Russia.

“But it’s amazing how he seems to have changed since then. He’s more relaxed, remembers everybody’s name and is generally easier to get along with. I don’t agree with a lot of the people who put him down. When he’s really playing—forget about it, he’ll scare you to death! There’s a good reason for his staying on top all these years. It’s because he can play his head off, and he’s had great bands.

“Anybody his age with his endurance is really incredible. He’ll rehearse for hours, and we’ll all be getting tired, but he’ll just be ready to play! One night he came down to the Half Note and sat in with Al Cohn and Zoot Sims, and he cooked everybody right off the stand. He must have taken 10 to 15 choruses on every tune. We’re all a bit younger than he is, but we were exhausted when he got through, and there he was, fresh as a daisy, and ready to play some more!

“Anybody that says he can’t play—well, they just aren’t around when he is playing. He practices two or three hours a day, and when we were rehearsing [for last fall’s tour, which was half jazz and half classical], he would play for three hours with the Berkshire String Quartet first—and then start in on the jazz group and rehearse for about five hours straight. He’s like a young kid with all that enthusiasm. It just never occurs to him to take a break, because he never gets tired. Most people practice because they have to, but he practices because he loves it.

“What’s he really like? Well, I’ve been around a lot of characters in my life, and I can usually predict what all of them will say and do, but you can’t predict what this guy will do from one minute to the next. When we were out with a group that had Jack Sheldon, Johnnie Markham and Flip Phillips, Benny was in a real jovial mood the whole time. He was telling jokes. Man, he was a riot. He’s got a brilliant mind for comedy, but not too many people know it.

“I feel I’m pretty qualified—more than most—to say I know him. A lot of guys have just had one brush with him, and they base everything, their opinion of him, on that one experience, which isn’t really fair.”

“I think a guy that can play as well as he does is entitled to a few eccentricities,” said Bobby Hackett, who was in the Lincoln Center group. “I’ve always found him to be most honorable all around. The trouble with him is that he just can’t get his mind off the clarinet. He’s like an absent-minded professor, mentally rehearsing all the time. That’s why he comes up with these strange remarks sometimes.

“I’ve worked quite a few weeks with him at different times, and they’ve all been beautiful. I think a lot of guys that criticize him subconsciously envy his success and his musicianship. Who do you know that pays the kind of salaries he pays? People just don’t pay that kind of money, not matter how much they have in the bank. He pays more than anybody and winds up getting criticized. It’s like when this country lends money to another country, you make an enemy. Tony Parenti told me a marvelous story once about Benny. In 1930 Tony subbed one night for him on Ben Pollack’s band, and instead of cash, Benny gave him a baritone sax! That wasn’t bad pay for one night.”

As marvelous a musician as Benny is, I did notice, however, his seeming lack of interest in rich harmonies. His music reflects this; he always has concentrated on the beat, rhythmic excitement, the melodic line. Lush voicings and chord changes evidently leave him cold. He seems to want the blandest possible changes behind him, and his improvisations are carried out strictly within this framework. It bothers him to hear an unfamiliar voicing—as I found out. This is his style, however, and his taste; I respect it as such.

As regards his expecting perfection, I can understand this better now, because sometimes I’ve found that with my own group, I will lose patience with a drummer or bass player, for not playing the way I think he should play, yet I haven’t really told him what I wanted to hear—I just expected him to know.

I think sometimes Benny (I’m second guessing, as he’s never actually told me this) will hire a musician and expect a great deal from him; then when he finds that he and this person don’t have the rapport he thought they would have, he sort of gives up and shuts himself off. I get the feeling that he expects a musician to know certain intangible things, and if he doesn’t catch on at once, then Benny mentally cancels him out.

As a teenager Benny worked harder and more consistently than most people. In fact, he has all his life, and I think he tends perhaps to have a lack of tolerance for people who don’t have as great a capacity for work and study as he has, which is understandable. I feel that putting down Benny has become a national pastime, and I wonder if the contemporary jazz stars will endure half as long musically, or as people, as he has. I think that at times one tends to grow too emotional about his behavior and that it might be a good idea to examine oneself occasionally, instead of always getting mad at Benny.

In retrospect, working for him was a great experience, one from which I have derived a good deal of insight into my own playing and into working with, and playing with, others. Despite all the pinpricks that seemed so important at the time, I haven’t changed my belief that Benny is a warm human being, and the paradox of it is that he also can be quite naive and gauche—in fact, at times he would make Emily Post faint. But he can be gracious and charming and fun.

Regardless of what people say in favor of, or against, Benny Goodman, his music has endured, and will endure. To quote one of Benny’s favorite expressions, “the old pepper” is still there … the old magic is still there. DB

Lena Horne

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)

Tony Williams

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)DB: The Bad Drummer Ordinance?

TW: Exactly. Anyone who does not study is shot! Seriously, though, it’s a big responsibility when you play the drums, and a lot of guys don’t want the responsibility, but they want to play the drums. The drummer is playing all the time. You can have a terrible band and a great drummer, and you’ve got a good band; but you could have great horn players, and if the drummer and the bass player aren’t happening, you’ve got a terrible band.

DB: Is tuning important?

TW: Yes. I hear drummers that have maybe 12 drums which all sound the same. If you closed your eyes, you wouldn’t know where they were on the set. Or else you’ll have guys where each drum sounds like it’s from a different set. It’s important that the drum set sounds like one instrument. Like, if you have a piano, you wouldn’t want the C to sounds like a Rhodes, the D to sound like a Farfisa, the E to sound like a Prophet. A keyboard is a uniform system; a trumpet is a uniform system … drummers are out to lunch. On some of my drums, the bottom head is tighter than the top head. On other drums they’re about the same. And on the bass drum the front head is looser than the batter side.

DB: Have you tried electric drums?

TW: Yeah! I tried the Simmons. The separation you get on tape is great. The programmability, the sound, the sequencing … it’s another thing to do that seems very interesting. I have a DMX [electronic, programmable drum machine by Oberheim] at home.

DB: Will electronic drums be part of what you’re doing in the studio?

TW: Oh yeah, they already are.

DB: Can you say anything more about what direction your music is going?

TW: The popular direction. I like MTV. I like the Police, Missing Persons, Laurie Anderson. I performed with her on a San Francisco date. It was great. I love the new Bowie album. Prince. I like the idea of writing lyrics, of putting images with words that evoke a scene on top of the music. I like Herbie’s new album. It’s really happening.

DB: Are you interested in making a video yourself?

TW: Sure. Growing up in this country, watching TV and movies, everyone would like to make a movie. It’s a new thing to do. You know writers want to be painters; screenwriters want to be directors. Musicians want to make movies. Doing a project and having a lot of people like it and maybe listen to it on the radio, that appeals to me. What I’m trying to do is something that captures a lot of people’s imaginations. If the result is I’m more famous, fine. But it’s not like I’m after being a pop star.

DB: You’ve said in the past that jazz should be popular, not an elitist art form. But isn’t it about time Americans claimed jazz as their art form and started recognizing it with the kind of respect they give European music?

TW: That’s a fine thought, but how much is that really going to do for musicians? I don’t think society really recognizes classical music, anyway. It’s all about patronage, and grants, a certain class of people. Jazz was originally the music of the people in the streets and not in concert halls, so when you lose that, you suffer the consequences. There’s nothing wrong with jazz being an art form, but it has certain roughness and vitality and unexpectedness that’s important. I guess I’m old-fashioned. DB

Dexter Gordon (1923–1990)

(Photo: Rob Bogaerts/National Archives of the Netherlands)

Claudio Roditi (1946–2020)

(Photo: David Gahr)

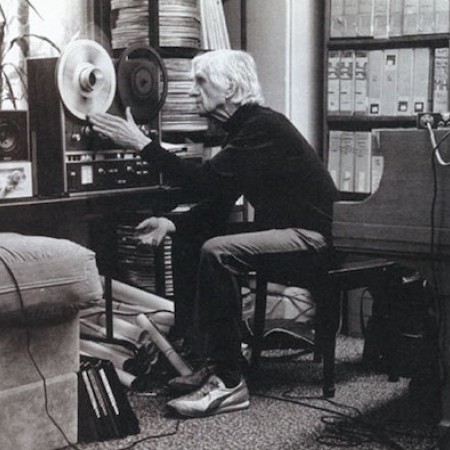

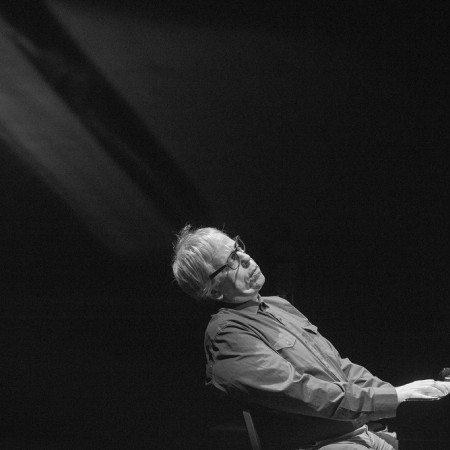

Gil Evans (1912–1988)

(Photo: Carol Friedman/gilevans.com)“A characteristic voicing for the Thornhill band was what often happened on ballads. There was a French horn lead, one and sometimes two French horns playing in unison or a duet depending on the character of the melody. The clarinet doubled the melody, also playing lead. Below were two altos, a tenor, and a baritone, or two altos and two tenors. The bottom was normally a double on the melody by the baritone or tenor. The reed section sometimes went very low with the saxes being forced to play in a subtone and very soft.

“In essence,” Evans clarifies, “at first, the sound of the band was almost a reduction to an inactivity of music, to a stillness. Everything—melody, harmony, rhythm—was moving at a minimum speed. The melody was very slow, static; the rhythm was nothing much faster than quarter notes and a minimum of syncopation. Everything was lowered to create a sound, and nothing was to be used to distract from that sound. The sound hung like a cloud.

“I should add, incidentally, that Claude’s desire was to avoid unnecessary activity even extended to the correction of mistakes. There was a minimum of discussion of the music. He hated to correct an error. ‘Find it yourself,’ was his attitude. If a guy was out of tune, Claude would touch the fellow’s note as he was passing through the harmony part on the piano, to show him the way it should be played instead of telling him.

“But once this stationary effect, this sound, was created, it was ready to have other things added to it. The sound itself can only hold interest for a certain length of time. Then you have to make certain changes within that sound; you have to make personal use of harmonies, rather than work with the traditional ones. There has to be more movement in the melody—more dynamics, more syncopation, speeding up of the rhythms.

“For me, I had to make those changes, those additions, to sustain my interest in the band, and I started to as soon as I joined. I began to add from my background in jazz, and that’s where the jazz influence began to be intensified.”

The next addition Thornhill made in modern band instrumentation was the tuba.

“In the old days,” Gil explains, “the tuba had been used mainly as a rhythm instrument. The new concept with Thornhill started when Bill Barber joined the band, around the middle of 1947 or in 1948. Claude deserves credit, too, for the character of the sound with tuba added.”

Gil returned to the jazz aspects of his work with Thornhill, saying, “I wrote arrangements of three of Bird’s originals, “Anthropology,” “Yardbird Suite” and “Donna Lee.” And I also got to know Charlie well. We were personal friends, and were roommates for a year or so. Months after we had become friends and roommates, he had never heard my music, and it was a long time before he did.”

(Gerry Mulligan explains: “What attracted Bird to Gil was Gil’s musical attitude. How would I describe that attitude? ‘Proving’ is the most accurate word I can think of.”)

“When Bird did hear my music,” Gil continued, “he liked it very much. Unfortunately, by the time he was ready to use me, I wasn’t ready to write for him. I was going through another period of learning by then.

“As it turned out, Miles, who was playing with Bird then, was attracted to me and my music. He did what Charlie might have done if at that time Charlie had been ready to use himself as a voice, as part of an overall picture, instead of a straight soloist.”

Thelonious Monk (1917-1982)

(Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Library Of Congress)

Lennie Tristano (1919-1978)

(Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Library Of Congress)

Joni Mitchell performs in 1983.

(Photo: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic)Did that expand your knowledge, being around them so much?

Not really, not in an academic sense. It gave me the opportunity to play with a band and to discover what that was like. But I still was illiterate in that I not only couldn’t read, but I didn’t know—and don’t to this day—what key I’m playing in, or the names of my chords. I don’t know the numbers, letters or the staff. I approach it very paintingly, metaphorically. So, I rely on someone that I’m playing with, or the players themselves, to sketch out the chart of the changes. I would prefer that we all just jumped on it and really listened.

Miles always gave very little direction, as I understand. It was just “Play it. If you don’t know the chord there, don’t play there,” and that system served him well. It was a natural editing system. It created a lot of space and a lot of tension, because everybody had to be incredibly alert and trust their ears. And I think that’s maybe why I loved that music as much as I did, because it seemed very alert and very sensual and very unwritten.

And you, in turn, trusted your own ears.

I do trust my own ears. Even for things that seem too outside. For instance, sometimes I’m told that So-and-So in the band, if I hadn’t already noticed, was playing outside the chord. I see that there’s a harmonic dissonance created; but I also think that the line that he’s created, the arc of it, bears some relationship to something else that’s being played, therefore it’s valid. So, in my ignorance, there’s definitely a kind of bliss. I don’t have to be concerned with some knowledge that irritates other people.

“Outside” is only a comparative term, anyway.

Outside the harmony ... but still, as a painter, if the actual contour of the phrase is, like I say, related to an existing contour that someone is playing, then it has validity. Like, if you look at a painting, there seem to be some brush strokes that seem to be veering off or the color may be clashing, but something in the shape or form of it relates to something that exists; therefore it’s beautiful.

I see music very graphically in my head—in my own graph, not in the existing systemized graph—and I, in a way, analyze it or interpret it, or evaluate it in terms of a visual abstraction inside my mind’s eye.

Where did you first hear about Mingus?

I remember some years ago, John Guerin played “[Goodbye] Pork Pie Hat” for me, which is one of the songs that I’ve done on this new album; and it was that same version. But it was premature; he played it for me at a time when it kind of went in one ear and out the other. I probably said “hmm-hmm,” and it wasn’t until I began to learn the piece that I really saw the beauty of it.

Mingus, of course, was a legend. Folk and jazz in the cellars of New York were overlapping, so I’d heard of Mingus by name for some time. As a matter of fact, I’d heard that name as far back as when I was listening to Lambert, Hendricks & Ross in Canada. I was in high school then, but my friends in the university spoke of these legendary people. That was in the early ’60s.

When did you actually get to meet him?

I got word through a friend of a friend that Charles had something in mind for me to do, and this came down the grapevine to me. Apparently, he had tried through normal channels to get hold of me; but there’s a very strong filtering system here and for one reason or another it never reached me. So, it came in this circular way, and I called him up to see what it was about, and at that time he had an idea to make a piece of music based on T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, and he wanted to do it with—this is how he described it—a full orchestra playing one kind of music, and overlaid on that would be bass and guitar playing another kind of music; over that there was to be a reader reading excerpts from Quartet in a very formal literary voice; and interspersed with that he wanted me to distill T.S. Eliot down into street language, and sing it mixed in with the reader.

It was an interesting idea; I like textures. I think of music in a textural collage way myself, so it fascinated me. I bought the book that contained Quartet and read it; and I felt it was like turning a symphony into a tune. I could see the essence of what he was saying, but his expansion was like expanding a theme in the classical symphonic sense, and I just felt I couldn’t do it. So, I called Charles back and told him I couldn’t do it; it seemed kind of like a sacrilege.

So, some time went by and I got another call from him saying that he’d written six songs for me, and he wanted me to sing them and write the words for them. That was April of last year, and I went out to visit him and I liked him immediately; and he was devilishly challenging.

He played me one piece of music—an older piece, I don’t know the title of it—because we figured it was going to take eight songs to make an album: the six new ones and two old ones. So, we began searching through this material, and he said, “This one has five different melodies,” and I said, “And you want me to write five different sets of lyrics at once,” and he said “Yes.”

He put it on and it was the fastest boogieingest thing I’d ever heard, and it was impossible. So, this was like a joke on me. He was testing and teasing me; but it was in good fun. I enjoyed the time I spent with him very much.

Trumpeter Lee Morgan (1938–’72) performs with the Jazz Messengers on Nov. 15, 1959, at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam.

Art Tatum (1909–’56)

(Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Library Of Congress)

Lee Konitz (1927–2020)

(Photo: Jimmy Katz)

Sarah Vaughan (1924–1990)

(Photo: Nationaal Archief, The Hague)Her skillful, natural, and frequent changes of key and her use of improbable intervals give each of her performances a freshness and originality unmatched by any other singer. With her, enunciation is completely subservient to music.

Vaughan doesn’t waste her singing. She loves to sing but does so only for a purpose. She must have an audience she cares about. It need not be large. Once, reportedly, she sang for an audience of one. Shortly after her engagement to Atkins, she called him in Chicago from New York and sang one of her best-known ballads, “Tenderly.”

There are, in fact, times when it seems everyone wants to sing but Sarah.

Once, in 1960, she made the alarming discovery that her husband, her maid, and her pianist all felt the magnetic pull of the spotlight. A member of her accompanying trio recalls, “Man, those trips in the car from one gig to the other were something else. We had great singing contests, and we tried to get Sarah to be the judge. Each one of us would sing his or her best number. It was too much, now that I think about it. Everybody was singing but Sarah.

“She was just sitting in the corner, wishing everybody would shut up so she could get some sleep.”

Most of the early fears are conquered now. In their place have come problems of adjustment, and some new fears.

But Vaughan has never looked healthier or happier. She makes no decision regarding either her career or her personal schedule without her husband’s approval. She is openly adoring of him, and obedient to the point of subservience. Often she sits quietly, watching him, hanging onto every word. If he asks her to do anything, she is off like a shot.

She is almost childlike in her anxiety not to displease him. If in his absence she goes for a moment against his wishes, she is almost instantly contrite, hoping he will never find out what she has done.

“I guess I’m too sensitive,” she admits. “But I’m so afraid of being hurt. I’ve been hurt so much.”

Onstage, she alternates between revealing herself as the pixie-ish Sassy and the sedate Miss Vaughan. At those moments when the old fears and nightmares peek through, it is the little church organist from Newark who stands there with the cloth of her skirt between her fingers, holding on tightly. It is then that she wants to slow the pace and spend more time as Mrs. Atkins.

“What’s the use of having a home if you can’t enjoy it?” she asked. “Of course, I want to keep singing as long as anybody will listen. But I want to spend more time at home.”

She is tired of the public demands on her and, although she remains gracious when she is talking to them, she resents autograph hounds and pushy people generally.

When her husband reminded her recently that this was a part of her responsibility as a star, she replied, a little pathetically: “Honey, I’m tired of all this. Let me just be Mrs. Atkins, and you be Sarah Vaughan.” DB

Stan Getz (1927–1991)

(Photo: Lee Tanner)The trouble with most of the Danish jazz musicians, however, is that they are hobbyists—though very good ones—for whom it apparently doesn’t pay to play for a living. Perhaps as the interchange of jazzmen increases, the climate will be more propitious for careers in jazz. It is already getting better, as evidenced by the fact the daily press devotes a considerable amount of space to jazz columns and reviews. Denmark also has two regularly published magazines devoted to jazz.

Two of the best jazzmen in Denmark are Jan Johansson, a lean young Swede with a beard and a modest manner, who has been influenced considerably by Horace Silver and Lenny Tristano; and William Schiøppfe, a poll-winning drummer who has learned from the two Joneses—Jo and Philly Joe—and is the only Danish musician who makes a full-time living from jazz.

Both have played extensively with Getz, in the house group at the Club Montmartre.

Johansson recalled his first few nights of playing with Getz and Pettiford: “They were, of course, excellent,” he said. “I was terrible. American musicians like Stan and Oscar not only play better than most Europeans, but in many ways are quite different from us. They have more nuances, they are more forceful, bolder. The rest of us are so busy trying to keep up with them that we rarely reach the great moments. ... European musicians spend a lot of time listening to American jazz on records; we seem to be less independent in our playing.”

Another young musician, Lars Blach, a Danish guitarist who occasionally sits in with Getz and Pettiford, speaks with even greater awe: “Of course, it’s wonderful to be allowed in with such company. At first you think it’s strange that they’ll have you sit in at all. There you sit—small, mean with big ears—waiting for that knowing smile that tells you that you’ve failed. But suddenly you realize that the other guy gets something out of even your worst blunder! ... Then afterwards you rush home with your head full of new ideas and try them out.”

This, then, is the present world of Stan Getz: a favorable, relaxed atmosphere in which he is able to play without pressure, in which his work is able to grow and his influence take root among musicians who need the inspiration he and Pettiford can give. And make no mistake: He is making a real effort to grow as an artist.

He sat down to talk about it one night at the Montmartre.

As it happened, it was one of those wrong nights. The Montmartre was half empty (a rarity), and the first few sets by the group were undistinguished to the point of being restive. Getz had had a bad day. Yet, suddenly he launched into a 12-minute version of “I Can’t Get Started,” during which he poured out his soul with extraordinary beauty and lyricism. The audience was transfixed.

Afterward he seemed to feel better.

“My music gets better when I have time for meditation and working new things out,” he said. “I have been working a lot with my tone over here. I’ve been trying to set it more naturally. I’m trying to get away from too much vibrato. ... I started off the wrong way, learning the practical aspects first. It’s a blind alley.”

To achieve his ends, Getz plans to enroll at a Danish music conservatory to study theory, and learn to play piano. He has, believe it or not, never had a formal music lesson since he began playing professionally in New York at the age of 15.

This devotion to improvement is already paying off. As Gitler detected from the Getz recording, his playing has reached a new maturity. The style has become more lyrical, yet increasingly forceful.

“He doesn’t seem dry and intellectual as he used to,” said one Danish jazz critic. “He has soul in every note he plays. ... Getz demonstrates that the modern school isn’t as bloodless as people have been thinking. He builds up his themes with unerring logic, and it is almost incredible that he can give his tone so much richness and fullness without vibrato ... .”

Getz has no intention of leaving Denmark at this time. Why should he?

He and Pettiford do considerable radio work, mostly with the intelligent planning of Børge Roger-Henrichsen, a jazz pianist who is in charge of jazz programming for the Danish state radio. And there is recording work. Pettiford does some recordings with small European groups for Dyrup, the Montmartre proprietor, who also owns a record firm and distributes American labels such as World Pacific, Savoy, and Roulette. Getz said that he plans to join Pettiford when his contract with Verve runs out.

Getz and Pettiford usually play four nights a week at Montmartre. During the weekends, they either play to one of the hundreds of jazz societies that have sprouted up all over this little country in recent years. Or they hop a flight to some other European city for a weekend gig.

And that is one of the main appeals of Copenhagen to Getz: It is so located that no major European city is more than a few hours away by air.

In point of fact, Getz at this time is away from Copenhagen, traveling the continent with Norman Granz’s Jazz at the Philharmonic troupe. With him are the Oscar Peterson Trio, Miles Davis—and Jan Johansson and William Schiøppfe. The pianist and drummer—modest in evaluating their roles in the career of Stan Getz—so impressed Granz when he went to Montmartre to talk to Getz recently that he hired both of them to work with the saxophonist on the tour.

When they return, it will be time for Getz to start thinking about the summer. During the summer months, he and his family rent a large home facing Øresund, the sound that separates Denmark from Sweden.

It is an easy drive into town for Getz, who uses a small German car. He explained that he brought a large white Cadillac with him from America, but promptly traded it in. “I didn’t want any notoriety,” he said, grinning.

But chances are that in the vicinity of his home, you’ll find Stan Getz using an even more modest mode of transportation. Adapting himself to the local atmosphere, Getz does what the Danes do: as often as not, he travels by bicycle.

“Yes, I like this life,” the quiet-spoken musician said. “It’s a good life.” DB

Lionel Hampton (1908–2002)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)

Benny Golson genuinely is excited by the opportunity to write good music in any genre.

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)

Woody Herman (1913–1987)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)

Chet Baker (1929–1988)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)

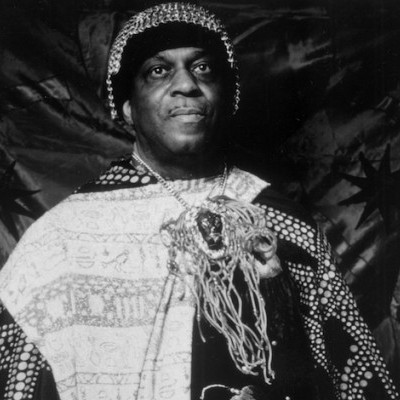

Sun Ra (1914–1993)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives/Impulse!)

Ella Fitzgerald (1917–’96)

(Photo: Verve)

Jelly Roll Morton (1890–1941)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives/Nonesuch)

Billie Holiday and her dog, Mister, in New York City during February 1947

(Photo: William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress)

Oscar Peterson (1925–2007)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives/Verve)

Mahalia Jackson (1911–1972)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives/Columbia Records)

Ornette Coleman (1930–2015)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives/Verve)It’s the same as in the music. You have a thing that you know about, how to get to it, but then you have to find a way ...

... to activate it.

People who are working at a high level, they’re struggling to take what they would like to do and bring it out. I can hear it in your music. It’s also a quality of vulnerability. That’s one of the only exclusively human qualities. You’re not trying to dominate something, as you’ve said.

What’s so free about it, you don’t have to hunt for it, it will appear. It’s not coming there because of you, it’s coming there because it exists. Life itself is dealing with those problems every minute. The quality of knowledge is not class, race or sex. It’s creation. If you have an idea and you put it down and materialize it, that’s as good as you can do.

I’m sitting here speaking to you and I know that if I got my horn out and played it, I would be doing that for the same reason I’m speaking to you: to bring something that has a meaning to the surface. We are all living, breathing, working, supporting each other, but there’s no human being up here and down here. That’s not human.

Doing is believing. That’s one way you know you exist.

That’s such a beautiful statement, and it seems to relate to the long musical relationship with your son, Denardo Coleman, which shocked many listeners when you debuted him as a child. But it showed how people could work together, be a parent, a bandleader, but also just be together.

There’s nothing in the way of it getting better. Nothing! Just you, your heart, your brain and the love that you wish to express because of what it means to you. Doing is believing. It’s the whole thing. Doing doesn’t get destructive, doesn’t have to be above or below, it’s right there.

Like surfing. When a surfer gets right where the wave breaks, everything is suspended. The fact of riding the wave has consequences, comes from someplace, but for that moment everything is halted. Your music can do that to me. On alto saxophone, in your hands, the act of doing is an act of belief.

You couldn’t say it any more clearly, eternally. How you describe things, you describe them in an eternal way, and you don’t have to describe things, you only have to activate it. It has to do with two things: love and life. There’s nothing in between. I’m trying to free myself from surviving, but I’m not sure if I’m going to survive, because I’m not clever enough. Who knows my weaknesses? I don’t even know them. I want to find the idea before it’s thought of, so I can be prepared for it. When I take my instrument, I know it too well; when I get ready to execute, I know the way I have to move my fingers, and I know that too well. Because of that, I’m not sure I want to do it that way. I’m only trying to make contact with life. We can make contact with life. It exists.

Was that behind your choice to move to violin and trumpet, instruments you didn’t have training on?

Those things have another way of adding to what the idea could replicate. I’m glad you brought that up. Suppose you couldn’t read or write, but you could pick up a horn and play everything anyone has ever heard? That can exist. That does exist. Trust me! Life doesn’t send you any bills.

So, according to life, you can pick up an instrument and play it ...

...instantly, as if you’ve been playing all your life.

You don’t have to play it according to all sorts of ...

... rules and conventions. The saddest thing in the whole world is when a human being makes another human being feel less than they are. DB

This story also appears in Microgroove: Forays into Other Music (Duke University Press). For more information on John Corbett’s work, visit his website.

“Doing shows and festivals under your own name, it’s a surprisingly big difference compared to playing with someone else,” saxophonist Kamasi Washington said, discussing the attention he’s received since the release of The Epic (Brainfeeder). “There is a lot of responsibility.”

(Photo: Mike Park)

Galt MacDermot (1928–2018)

(Photo: Dagmar/DownBeat Archives)“It was no big theatrical event, just a setting of the Anglican service. I would like people to do it. In my daughter’s school, in fact, the kids all know and sing it. It’s like a hymn, one long hymn, and that was the idea of it. In addition, I’ve been writing a wind quartet for my wife, who used to play clarinet in an orchestra. It’s a nice thing for a composer to do, and it’s fun. I wrote a few such things when I was going to school, and I do the arrangements for the shows I write. But doing this is altogether different from writing for a 14-piece band where you have a rhythm section to carry it and you use the brass to fill. This is completely carried by itself. It’s fanciful composing, but it has a little of that African feeling. The rhythms are West Indian, and every time I play piano, it tends to have that West Indian lope. The heavily African beat is much more in West Indian music than it ever was in jazz. The guys in the quintet are classical, however, very Juilliard-type guys.”

Alongside all these activities, he has for a considerable time been making records as Fergus McRoy, a pseudonym for a Nova Scotian folksinger.

“I have a record company of my own, and I’ve made several albums. A guy in Canada has been trying to sell them, without much success, and arrangements are being made for their distribution here on the Kilmarnock label. The first batch will include Ghetto Suite, a couple of film soundtracks, the original cast recording of Isabel’s a Jezebel, two of McRoy’s sets, a rock album and so on. My name isn’t really known and I haven’t bothered about promotion. That way, I stay free of the business end of things. Because I write all the time, I’ve written hundreds of songs, and I like making records. Fergus McRoy, this character I’ve created, provides me with a way of using them. I suppose a few people might be interested, but the record business is very much tied up with promotion, and promotion is so boring, tiresome and demoralizing that you’d rather quit than put up with it all. Except that you don’t want to quit the business of music.”

“I think the record industry has had a serious effect on young people, in making them think there’s only one way to write. When I was growing up, I wanted to write symphonies and operas, and then I wanted to have a band like Duke Ellington’s. There were all kinds of things I wanted to do. I lived in a dream world, and because I didn’t know the realities of anything, there were all kinds of interesting possibilities. But nowadays, the only thing you can hear is a hit record, or Muzak, which you don’t really listen to. So, it’s hard to say how kids’ tastes are formed now. When I was young, one or two of us used to go to the store every day to find out about new records. Our son, who’s 14, listens to the radio for hours, and sometimes he tapes half a record he wants to hear again. But not jazz, nor the other kind of records I grew up with, the fantastic kind we used to call ‘race’ records. I don’t hear anything like them anymore, except really commercial versions. Where is the counterpart of Joe Turner, the young guy like him?

“As I said earlier, I don’t feel much is happening in pop music, but you tend to say this every six months, that there’s nothing happening, and the next thing you know something happens that you like. But everything gets exploited so heavily. I like country music, but I can hardly take the country records I hear now. The same with rhythm and blues. You don’t hear new ideas; people are afraid of ideas. They want to get that funky feeling—and I like that—but if there’s no idea you can’t go far.

“You can identify the source of nearly everything played by the young jazz guys coming up. They’re not original. An Erroll Garner can’t happen anywhere but here, although for some reason it doesn’t seem to have been happening recently. I think the reason may be economic, or the fact that the hit record is all anyone aims for. That used to not be so when I played in a dancehall, when we made the people dance. There was a whole different way of playing, when you worked on the rhythm, and over a period of time something would happen. Now, the kids don’t get work until they have a hit record, and then they don’t know what it is they’re trying for.

“As for jazz being an expression of some kind of political or ideological belief, I don’t think politics is worthy of a musician’s consideration at all. It’s like tax collecting. Of course, money is important to you, but it’s not interesting. Music is so much more important. I’m always astonished when I hear musicians talking about politics, just like they talk about their cars.”

MacDermot’s career obviously has been anything but boring. To attempt to predict its future course would be decidedly foolish, but all those who were delighted by the freshness of the approach to Two Gentleman of Verona will scarcely be surprised to know that more Shakespeare with his music is in the offing. After he finished Hair, he went back to producer Joseph Papp ready to write an opera. They had discussed this before, and Papp now suggested the relatively little known Troilus and Cressida.

“There’s terrific poetry in it, and little speeches, which make nice songs. When I had finished it, Papp didn’t know how to deal with it, either. I rather wanted to drop it. But there is some music I like in it, and I’m thinking of making a record of it. One of the problems was whether it should or should not be in suits of armor. I felt it ought to be in the clothes people wear now. The fact that Shakespeare’s not easy to understand was another difficulty, especially since all of it, in this case, would be sung. Tom O’Horgan wants to do a Broadway version of it, but I can’t imagine people going to a Broadway theater and understanding it. He believes, and I partly agree, that if you keep the eye delighted and the ear amused, it will be acceptable enough. It is, after all, a simple story about a guy and a girl falling love, but it’s not a mass thing in the same sense as Superstar.

MacDermot has also written a musical about outer space called Via Galactica, which Nat Shapiro wanted to produce.

“I’ve written another show with Gerry Ragni called Dude. It’s about American life, the same kind of thing as Hair. Ragni has the extraordinary view of things. He sees them differently. He is in his mid-30s, a very interesting guy who writes in a strange way. He has a jazz mentality, and, instead of lyrics, he lists ideas. They are not in song form and you have to do the best you can. That’s how Hair was done.”

Both shows are due on Broadway this season. DB

Nancy Wilson (1937-2018)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)

Kenny Werner

(Photo: Alessandra Freguja)

Pianist Teddy Wilson (1912–1986)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)Wilson’s first nonrecording job with Goodman was at the Congress Hotel in Chicago on Easter Sunday, 1936. Hammond drummed up the idea of Sunday afternoon jazz concerts at the hotel with outside musicians as guest stars, and Wilson was one of the first to be featured. He was such a hit that he was asked to join the band as a steady member.

As the first Negro featured with a nationally known white band, did Wilson have much trouble with racial prejudice while working with Goodman?

“Only in regards to hotels ... sleeping accommodations and hotel restaurants,” Wilson remembered.

Only in the South?

“Oh, no, North and South. And there was another thing, too. The first movie we did—I think it was called The Big Broadcast of 1937, something like that—the movie people wanted me to play the soundtrack but wouldn’t allow me to be photographed. I didn’t agree to that, and I wasn’t in the movie.”

Speaking generally of the swing era, Wilson said, “It was a very exciting period. The Goodman band was the first jazz band to become a nationally popular thing, and it took us all by surprise. No one expected it. And in those years, the audience would even applaud a good figuration. You never see that now!

“Of course, a big part of the audience was sensitive to showmanship— the drum solos, for example—but a good many people in the audience were obviously musically sensitive. In contrast, the audience today is so jaded. They have to be entertained. It’s a problem that young musicians must face.

“Music is something like baseball, movies, or any other entertainment medium in that respect. It isn’t easy, and it sometimes calls for values that are not musical. Today, music is not the thing, as it was then. I imagine it’s discouraging for a good young musician today when he sees how successful a mediocre musician can be.”

Teddy said he believes that a major reason why the Goodman band was able to become the first nationally popular jazz band is because Benny kept music at danceable tempos. He elaborated: “Goodman would sometimes stand in front of the band, tapping his foot for as long as a minute, almost as if feeling the pulse of the dancers, to assure the proper time.”

Wilson added that the band had “a good sound, one of the great clarinet players, good intonation in the reed section, first-rate trumpet work and other musical values, and it was playing within the dance tradition.”

Wilson said jazz has lost the mass audience, partly because it came to ignore dancers. “And so rock ’n’ roll, as bad as it is, is filing the vacuum. Ellington, of course, has always had high musical standards, as well as a good dance band, too. He’s done an amazing job over the years to keep his band in touch with the public while doing other things in music, too.”

Wilson left Goodman in 1939 to form his own big band. The band lasted about a year and was not a commercial success, although it won high praise from musicians and critics. Of this band, Wilson said: “The band simply didn’t have much mass appeal. We didn’t have enough show pieces. We played good dance music, but we needed 10 or 20 good stomp head arrangements to add the excitement that was missing. The mistake I made was in concentrating too much on written arrangements.”

From 1940 to 1944, Wilson fronted an all-start sextet at the two Cafes Society, Uptown and Downtown, and in 1945 he rejoined Goodman, working with Red Norvo and Slam Stewart in the Goodman sextet.

During the next decade, Teddy was in studio work most of the time, as a staff musician at New York’s WNEW and later at CBS. He also taught annual summer classes on jazz piano improvisation at Juilliard. Since the 1956 Goodman movie, Teddy has made more club appearances, notably at the New York City Embers. Currently, he is using Bert Dahlander, the Swedish drummer, and bass man Arvell Shaw in his trio.

Although he has not taught for some time, Wilson remembers and is typically quick to praise his former students, particularly John Ferrincieli, who “played stride piano against a modern type of right hand,” and William Nalle, now in studio work. “I had some other talented students, too, and I am talking about real piano players,” he said.

As might be expected from a two-handed pianist who understands that a piano is not a drum, a pianist whose work has been distinguished by superb finger control, a keen sense of dynamics, master legato playing, originality, love of melody, a compelling and resilient beat and a complete absence of gimmicks, Wilson does not think much of most contemporary jazz pianists.

“With few exceptions, what they play is a caricature of the piano,” Teddy said. “A caricature simply because of the way the piano is made. And pianists today all sound so much alike.”

But Wilson, the schooled pianist, does not include Erroll Garner, who cannot read music, among the caricaturists. Teddy explained: “Garner brought a great deal of originality to jazz piano, working with his time lag. His phrases come through with such conviction because they are his own. On the other hand, when you imitate another musician’s way of playing and are too derivative, your phrases are not too clear, are just a shade vague, and they lack real conviction.”

Wilson, also a critic of modern rhythm sections, said, “Drummers today play a continuous solo, from 9 till 4. And I always thought a saxophonist like Parker would sound much better with a conventional rhythm section than with a hipster rhythm section. To my mind, if the background gets too complex, it kills the solo. I guess Dizzy and others like that kind of drummer and that kind of rhythm section, but I don’t. The Parker-like soloists would sound much better if they had simpler harmonic backgrounds; then their own harmonic thinking would come over far better.”

Wilson also said he feels that the development of records, ironically, has helped what he terms the “conformity” in jazz today.

“When I came up, there was a good deal of local influence,” he said. “We would travel 30 miles or so to hear another musician who had his own way of playing. Musicians developed different approaches to music in different cities. But today the same jazz records are available and popular all over. They influence young musicians in New York, Atlanta, Paris or Tuskegee at the same time. All this tends for conformity.”

Perhaps Wilson’s point of view concerning jazz today is best summed up with this offhand remark: “You have creative people and you have imitative people, and in a period of conformity, as today, there are more imitative people.”

What does he think of the music business today?

“I do feel that music has got to come back,” he said. DB

Pianist and bandleader Lynne Arriale once told a journalist: “Jazz should not be only for jazz lovers.”

(Photo: Juan Carlos Villarroe)

Randy Weston at The New School in New York

(Photo: Jimmy & Dena Katz)Max Roach, also a Boys High alum, lived nearby, and Weston took frequent breaks to visit. George Russell, then convalescing from tuberculosis in Roach’s house, was working on “Cubana Be, Cubana Bop” for Gillespie’s recently formed big band, sometimes joined by Gillespie himself and trailblazing Cuban conguero Chano Pozo. Russell introduced Weston to Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, which struck him as “interesting but kind of cold,” and also to the corpus of Alban Berg, which affected Weston deeply.

Concurrently, Weston started to compose tunes, earning validation on an occasion when Roach, hosting Charlie Parker, his employer on 52nd Street, asked Weston to “play something for Bird,” who responded favorably.

“I’d sit and absorb what these giants said,” Weston said. “I had no idea I’d be a musician. My father, God bless him, wanted me to be a businessman. He wanted his son to be independent. Pop was fully aware of the racism in New York—in America, period. Segregation was serious! Even in Manhattan, we couldn’t go to restaurants. But Mom and Pop kept that spirit.”

Another transformative breakthrough occurred in 1951 at the Music Inn in the Berkshires, where Weston took a summer job as a breakfast chef. After completing his daily obligations, he played piano in the evenings. “Three older ladies told me they were having a recital, and wanted me to play,” he recalled. “I told them I didn’t play Bach or Beethoven, but they said, ‘No, we want to hear what you play at night.’ Then I realized I had something to say on the piano. But I was still very shy.”

Not long thereafter, Weston met the pioneering jazz historian Marshall Stearns, a bespectacled Caucasian professor of English with degrees from Harvard and Yale, who specialized in medieval literature. Stearns conducted colloquia at the Music Inn that offered a university-level education in the threads that connect jazz to the traditional music of the ethnic groups and regional styles of West Africa. “Marshall was the squarest-looking guy you’d want to see,” Weston said. “But he was Pan-African. He encouraged me to listen to older pianists like Jimmy Yancey and Meade Lux Lewis, who approached their instruments in a way closer to Africa. He brought in Macbeth the Great, a famous calypso singer, and I heard the French quadrille, which inspired me to start writing waltzes. He brought in John Lee Hooker and Jimmy Rushing, and did a 15-minute interview with Mahalia Jackson on African spirituality in the black church.”

On another occasion, Stearns arranged for a presentation by ethnomusicologist Willis James, who played field hollers that proceeded in 5/4 time; dancers Asadata Dafora and Katherine Dunham presented possibilities for sounds in motion; drummers Babatunde Olatunji and Candido authoritatively executed the rhythms for all to see and emulate.

Eventually, Stearns invited Weston to accompany his popular lecture demonstrations. After he suffered a heart attack in 1958, he asked Weston to deliver them. On Stearns’ recommendation, the U.S. State Department recruited Weston—who had visited and played in Nigeria in 1961 and 1963—to bring a group to tour in West Africa and North Africa at the beginning of 1967. “That’s when I realized I was an ambassador,” Weston said. “Marshall died before I had a chance to thank him. He taught me how to do the history of jazz.”

It could be said that, circa 2016, Weston—lineally connected to a timeline spanning Eubie Blake and Luckey Roberts to Ornette Coleman and David Murray—embodies the history of jazz in his own person. After soundcheck for the final New School concert, he stretched out on a sofa in the compact dressing room, listening to saxophonist/flutist T.K. Blue, bassist Alex Blake, percussionist Neil Clarke and tenor saxophonist René McLean trade stories about Slugs’ Saloon and the dangers of navigating Manhattan’s Lower East Side during the ’60s and ’70s. When directly addressing Weston, they called him “Chief.”

“It’s not something he claims,” Clarke said of the designation. “Randy is a chief by acclamation. He’s so generous, so inquisitive, so unflinching in his love and respect and appreciation for Africa. He’ll tell you the story of the creation of every single one of his songs, and the approach shifts. You don’t play licks or patterns. You participate in telling that story.”

Clarke has propelled African Rhythms for 20 years, sometimes within a uniquely configured percussion setup assembled from congas, djembe, cymbals and tambourine, sometimes playing alongside a drum kit player, sometimes not, always in uncanny synchronicity with Blake, whose approach to the bass evokes the guembri, a low-tuned Gnawan lute.

Weston told Pérez that using Clarke as sole percussionist provides him space to create harmonic color. “They all have digested the language, and that raises the level of freedom,” Pérez said. “When I hear the trio, I sometimes don’t know who’s soloing. They break down any preconceived idea about interaction, and connect it to the experience of the African neighborhood.”

Indeed, it is impossible not to notice how spontaneous and unpredictable Weston is, how rarely he repeats himself. He was asked how he sustains this optimistic, fresh perspective. He pointed to Fatoumata Weston, his Senegalese-born wife, whom he met in Paris in 1996.

“Every minute, I’m in Africa with her,” Weston said. “Everything she does—what she thinks, what she cooks, the clothes she makes for me—is African. And she’s from a spiritual family. I have a Senegalese family. Her daughter’s children treat me as grandpa. So, even if I try to go off the path, I can’t, because there’s my wife. She’s constantly giving. I can’t over-emphasize the importance of that. Dizzy would give. Eubie Blake. Duke. Max. Always giving. We got married in Nubia. The Creator said, ‘This is your wife.’ And I go with the flow.” DB

Eric Dolphy (1928–1964)

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)

Jack Bruce (1943-2014) continued playing jazz and blues while performing in Cream during the 1960s.

(Photo: Marek Hoffmann)The commercial success of Cream allowed you to do an acoustic jazz album, Things We Like.

I had this material, some of which I had written as a child, and hence the title, which was a reading book that you’d get in Britain. It was an opportunity to record with Dick Heckstall-Smith and Jon Hiseman. It started off as a trio, which the record was supposed to be. I’d written material for a trio and then I ran into John McLaughlin after the first day’s recording. We’d already recorded the first two tracks. He was a bit down, because he wanted to join Tony Williams in New York, but he didn’t have the money. So I said, “Why don’t you come and play on my record, it’ll give you enough money so you can go.” He came, and the rest of it is for a quartet.

I was planning my first tour with my first band, Jack Bruce & Friends, with Mitch Mitchell, Larry Coryell and Mike Mandel. The first gig we did in the States was the Fillmore East, two nights there. The first night Jimi Hendrix came down and Carla Bley, too. It was bizarre. The second night, John brought Tony Williams down. Tony said to me, “Do you want to join my band?” This was the opening of my U.S. tour with my first band! I said, “OK, sure man.” [laughs] Lifetime was just a trio at the time with Williams, McLaughlin and Larry Young. I don’t know why they had the idea of luring me in when they did.

Tony Williams Lifetime sounded like no one else. The albums don’t do it justice.

The problem that we had was trying to get that on record—it was so intense. We never managed to achieve that. The intensity made it almost impossible for the technology to preserve it. The people who actually saw a gig were blown away. I still get people coming up to me, in Europe in particular, saying, “I saw you at such and such and I was never the same again.” [laughs] It was unbelievable to play with Tony. It was like playing with Baby Dodds. He was the continuation of this tradition.

After working with Tony, you recorded with Carla Bley and Paul Haines on the three-record Escalator Over The Hill.

I’ve been listening to that again. I love Carla’s writing and her singing makes me laugh. It’s vast. There’s so much humor in it. I was playing with Don Cherry, Paul Motian. What can you say? It was amazing to be around, and there’s some good stuff on there, lots of imagination.

You crossed paths with Rahsaan Roland Kirk, too.

What a fantastic experience to play with him, but even better than playing with him was an astonishing gig at Ronnie Scott’s when he was doing his circular breathing thing, and he was playing this one note on one of his saxophones, and at the same time he lifted the bass player in his band, Malcolm Cecil, and threw him and his bass off the stand into the audience. [laughs] He had something out of this world. DB

Bassist William Parker is reaching an audience beyond the commercially restrictive categorization he refers to as the “avant-garde ghetto.”

(Photo: Courtesy of the Artist)

Marian McPartland and Mary Lou Williams in 1978, about 14 years after the two spoke for “Mary Lou Williams: Into The Sun,” which originally was published in DownBeat on Aug. 27, 1964.

(Photo: Courtesy of South Carolina Educational Television)

In 2013, ECM reissued Charles Lloyd’s first five albums for the imprint—Fish Out Of Water, Notes From Big Sur, The Call, All My Relations and Canto—as a box set.

(Photo: Courtesy Kurland Agency)

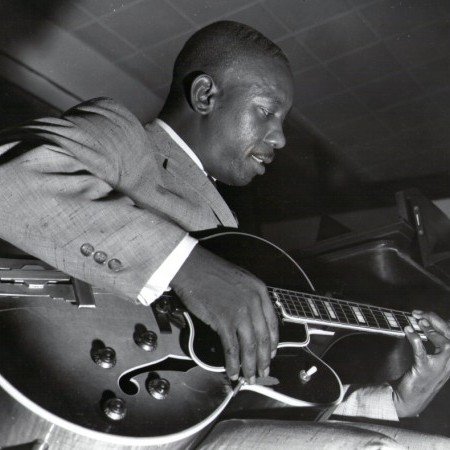

Wes Montgomery plays at the Essex House Hotel in Indianapolis in 1959.

(Photo: ©Duncan Schiedt/Courtesy of Resonance Records)

Sun Ra

(Photo: DownBeat Archives)

1993 NEA Jazz Master Jon Hendricks at the 2014 NEA Jazz Masters event.

(Photo: Michael G. Stewart, courtesy of National Endowment for the Arts)

Randy Brecker

(Photo: DownBeat Archive)

John Abercrombie (1944–2017)

(Photo: © Deborah Feingold/ECM Records)

Clark Terry (1920–2015)

(Photo: DownBeat Archive)

The Beatles

(Photo: Courtesy the artist)

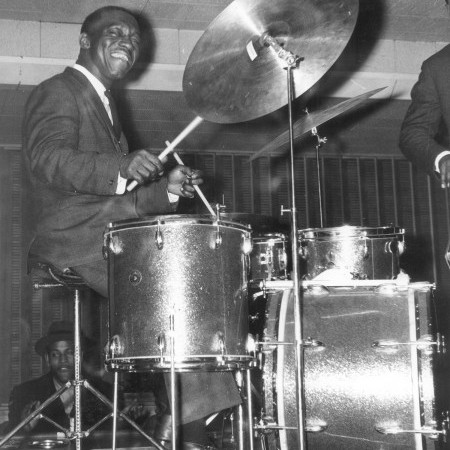

Art Blakey

(Photo: DownBeat Archives/R. Howard)

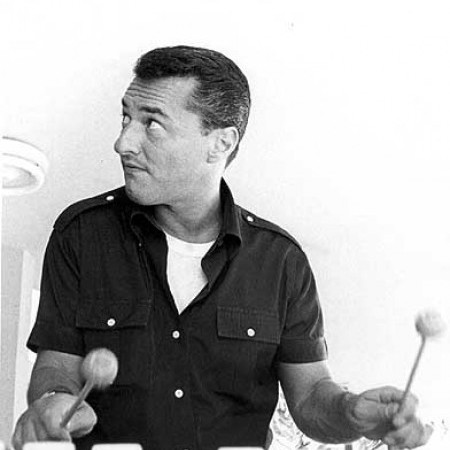

Terry Gibbs

Larry Coryell performs at The Jazz Kitchen in Indianapolis on May 23, 2015.

In late August, he began going to Chicago restaurants and sitting in with local bands. “I’d just walk up to them with my black Cort and ask, ‘Can I sit in?’ And they’d let me,” he said. “I did this over and over until I gradually started getting my strength back. I sat in at the Jazz Showcase during the Charlie Parker celebration that [venue founder] Joe Segal does every August. I played with Ira Sullivan. I listened to his band the first set, then I went up and said, ‘Can I play?’ He let me sit in, and he let me play as much as I wanted on the second set. Half the stuff I had never played before in my life … tunes like ‘I Get A Kick Out Of You.’ That was the best I ever played, and I didn’t even know the tune. It always goes like that. Tunes that I know too well I sound like shit on. Jazz is all about spontaneity.”

By October, Coryell had regained enough chops to go out on a mini-tour of Europe with a special edition of The Eleventh House that featured Joey DeFrancesco on trumpet and organ (filling in for Randy Brecker, who was performing in China) along with original Eleventh House bassist Danny Trifan (Lee was locked into commitments with the Dizzy Gillespie Alumni All-Star Band) and drummer Guido Bay (filling in for an ailing Mouzon, who was fighting a debilitating kidney disease).

The new Eleventh House album isn’t due out until June, but Barefoot Man should satisfy Coyell fans until then. His fleet-fingered solos are apparent from the funky opener “Sanpaku” to the mysterioso vibe of “If Miles Were Here” to the wailing “Improv On 97.” The collection closes on a swinging note with “Blue Your Mind,” which has Coryell dropping in quotes from “Flying Home” and “Seven Come Eleven” in tribute to Charlie Christian, another one of his guitar heroes.

Since recovering from his health scare this summer, Coryell has returned to the scene with a vengeance, exuding that same joyful spirit he brought with him to the Big Apple more than 50 years ago.

“Larry’s got this almost childlike enthusiasm about music,” Lee said. “It’s exhilarating when you’re about to go on stage with him because he’s always so excited to do it. It was the same way during my 10 years with Dizzy. We could be traveling 16 hours to get to a gig, and he might be exhausted, but once he hit the stage it was always a party. Dizzy was always excited to put on a good show, keep it positive and make it fun. And Larry’s the same way. He’s got a great energy and is such a loving, giving human being. I love this guy to death, man.”

(Editor’s Note: The preceding article was written by Bill Milkowski and published with the title “Back from the Brink” in the February 2017 issue of DownBeat. After the article’s publication, Larry Coryell wrote a letter to DownBeat, which was published in the Chords & Discords section of the April issue.)

Coryell’s Letter to DownBeat

I need to walk back some of the statements I made to DownBeat (“Back from the Brink,” February). I am no longer angry about the election; I accept it. I have musician friends who did not vote my way. I have no place implying, as I did in the article, that their votes were insincere or illegitimate; that is a sacred choice for all Americans and it needs to be respected.

Also—and this is very important—I believe that I have a responsibility to transcend politics, focusing instead on finding ways to touch people’s hearts through music. I never want to forget all the great players who mentored me in the art of demonstrating restraint regarding hot-button issues; these men and women advised me to exercise discretion, and to behave with exemplary humanity. I need to follow that advice.

I regret that I may have offended anyone. DownBeat is, after all, a journalistic haven for art and creativity. DownBeat and the other jazz magazines assiduously focus on America’s greatest art form: jazz. We need for these publications to continue their mission of creating value through promoting and exploring jazz. My comments did nothing to further the cause of our music. I apologize.

With best regards from Berlin, Germany,

Larry Coryell

(To read a preview of the forthcoming album by The Eleventh House, click here.)

Mose Allison

(Photo: Michael Wilson)

Louis Armstrong was elected into the DownBeat Hall of Fame via the 1952 Readers Poll.

Bobby Hutcherson (1941–2016) performs at Jazz at Lincoln Center in 2008.

(Photo: Frank Stewart)Cowell says that the band was definitely in the zeitgeist of the turbulent anti-establishment era. “We were all embracing the political content of the music, versus issuing the traditional and conventional,” he says. “Our approaches varied. We used sounds prevalent at the time and played in a free form. Our resources were expanded as we set out to re-examine the music. The apex for me came at a concert we had in Antibes [France]. There were great moments at that show where we combined pulses with a great deal of freedom within a fixed form. Bobby was doing these incredible cadenzas. The last time I saw him, he still was. He’s a happy person.”

Hutcherson’s move from SoCal to San Francisco was hastened by a Pasadena friend, Delano Dean, who opened up the Both/And club (which is where he met his second wife, Rosemary Zuniga, who was a ticket-taker). There was a lot of activity there, not only at Keystone Korner, The Jazz Workshop and the Blackhawk, but also in Golden Gate Park. He set up roots in the city and later, Montara.

Henderson also made the move to San Francisco. The tenor saxophonist and vibist formed a trio with drummer Elvin Jones and toured the country. “Joe and I became very close,” Hutcherson says. “He always had a hair-cutter there. When we were on the road, I brought along a pair of shears and gave him haircuts.”

One time after a tour, Henderson called Hutcherson up in the middle of the night.

He said, “Hey, Bobby, what are you doing?”

Hutcherson replied, “What’s going on? Is there some record date or a concert?”

“No, will you come over and give me a haircut?”

“It’s 4 a.m.”

“Come on over and we’ll have a good time.”

Hutcherson went, snipped and ended up staying there until the next afternoon, hanging out and talking. He heartily laughs when he tells the story, adding that he’s got so many more great stories that his wife and three sons have encouraged him to write a memoir.

He laughs again, then notes that he’s slowing down. “I’m not the dynamo I used to be,’ he says, laughing again. “I have emphysema, and I’m breathing oxygen while I’m talking to you. I can’t play long solos like I used to be able to, and I don’t play quite as fast because that takes a lot of oxygen.” During the winter months with Montara’s cold, wet weather, it’s been rough for Hutcherson, who has been hospitalized several times in recent years. Still, he says, “My doctor keeps telling me I’m doing well. That way I can continue to share my life and my music. What a reward that is.”

DeFrancesco seconds that notion. “Bobby is the greatest vibes player of all time,” he says. “Milt Jackson was the guy, but Bobby took it to the next level. It’s like Milt was Charlie Parker, and Bobby was John Coltrane.”

DeFrancesco first played with Hutcherson in a duet setting in 2002 at Pittsburgh’s Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild, on the suggestion of the executive producer, Marty Ashby, and the pair continued playing in a trio setting with a drummer. As for Somewhere In The Night, the booker for Dizzy’s Club, Todd Barkan, knew Hutcherson from his days at Keystone Korner. (Barkan has been relieved of his Jazz at Lincoln Center duties and now curates shows at the Iridium.) “It was incredible,” DeFrancesco says. “The music was harmonically deep and so soulful. Bobby picked everything to play. When you play with a legendary guy, you let them play in their element.”

One time in recent memory when Hutcherson was totally out of his element was when he was asked in 2003 to be a founding member of the SFJAZZ Collective. He was the elder statesman working with an array of young jazz stars, including saxophonists Joshua Redman and Miguel Zenón, trumpeter Dave Douglas and pianist Renee Rosnes. Hutcherson stayed on until 2007.

“That was four wonderful years, and I was the old guy in the group,” Hutcherson says. “It was something completely new to me. I was thrilled to play, but I was also very humbled. What a learning experience that was — being with the younger players. I learned forgiveness, to forgive myself. I wasn’t able to play as fast, and sometimes I’d miss notes and feel bad. But all the players made me realize that I had to forgive myself and keep going. That was the biggest lesson. And I continue to work on this every day. It’s a good practice.” (On Jan. 23, Hutcherson played at the SFJAZZ Center’s grand-opening concert.)

Looking back at his career now, Hutcherson waxes philosophic. All the trophies he’s received and the plaques pegged on his walls aren’t the point, he says. “Slowing down, I see a lot more,” he says. “The real plaque for me is to be able to share my music with others.” He pauses and then adds, “There’s still a lot to be revealed.” DB

Freddy Cole (1931–2020)

(Photo: DownBeat Archive)“But John Lewis was my favorite,” he says. “I just loved his touch and his feel. I learned how to play John’s solos note for note, especially things like ‘Three Little Words,’ ‘Though Swell’ and those things with Lester Young around 1950. He was the man I most imitated because he was playing at a level that I could reach. It’s not how fast or how many notes you can play. And John had a clear voice. This is how young people learn. You literally copy someone. When you master what someone else can do, then you add to it, subtract from it, and play with it.”

Cole works with a trio of guitar, drums and bass, which gives him smooth support and well-crafted solo work. Sitting in the audience, the listener hears Jerry Byrd’s buoyant guitar work and the graceful dance of Curtis Boyd’s brushes. But as a performer, Cole hears something else that may surprise.

“Maybe most listeners don’t pay that much attention to bass,” he says. “But the bass is the most important instrument in the band. You can ask a drummer to lay out. But the bass player—damn!—you’re nowhere without him playing the right notes. I get all my cues from the bass player. People think a singer gets the changes from the piano player. But I hear through the piano to the bass. I can sing around a piano player, but not the bass.”

Cole is so emphatic, one might think for a moment that his main influences as a singer have been from bass players. But not so. Many singers have cast their sway upon him. “There were so many,” he says. “Billy Eckstine is still one of my favorites. I also like a guy named Bull Moose Jackson. He played saxophone, too. There were blues singers, too—Andrew Tibbs used to be around here in Chicago years ago. I feel blessed because I was ale to hear so many of these people. I listened to so many songs and singers on the radio. I’d pick up on lyrics that way.”